Also by Robert Jeffrey

The Barlinnie Story

A Boxing Dynasty (with Tommy Gilmour)

Real Hard Cases (with Les Brown)

Crimes Past

Glasgow Crimefighter (with Les Brown)

Glasgows Godfather

Gangs of Glasgow (first published as Gangland Glasgow)

Glasgows Hard Men

Blood on the Streets

The Wee Book of Glasgow

The Wee Book of the Clyde

*

With Ian Watson

Clydeside People and Places

The Herald Book of the Clyde

Doon the Watter

Images of Glasgow

Scotlands Sporting Heroes

A large number of people gave assistance in the production of this book. In particular I would like to acknowledge the help of the following people and organisations: The staff of the Glasgow Room in the Mitchell Library, the staff of the National Archives, Charlotte Square, Edinburgh, James Anderson, Johnnie Beattie, Les Brown, Dr Kathy Charles, Mrs E. Cook, Aileen Donald, Joe Dunion, Haig Ferguson, Kendal Ferguson, Charles Gordon, Mary Gordon, Harvey Grainger, John Hamilton, Elsie Ironside, Jim Ironside, Stuart Irvine, Peter Jappy, Dr Grant Jeffrey, Ed Johnston, William Johnston, Tommy Laing, Willie Sonny Leitch, David Lovie, Dick Lynch, John Mathers, Jim McBeth Daily Mail, William McIntyre, Dorothy McNab, Mr X, Walter Norval, Liz Park, Peterman, Tam Purvey, John Quinn, Ronald Ross, Ed Russell, Tony Russell, Patrick Smith, Bob Smyth Sunday Post, Catherine Stevenson, Dorothy Thomson, Bert Watt, G. J. Wilson.

CONTENTS

Each man has an ambition and I have fulfilled mine long ago. I cherish my career as a safe blower. In childhood days my feet were planted on the crooked path and took firm root. To each one of us is allotted a niche and I have found mine. Strangely enough I am happy. For me the die is cast and there is no turning back.

John Ramensky, Barlinnie Prison, 1951

1

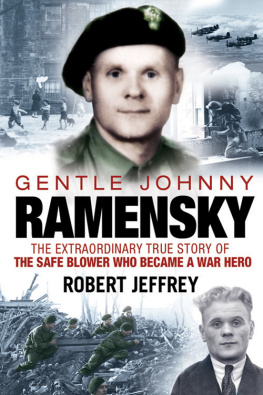

It was a hard childhood in a hard village Glenboig in North Lanarkshire. And later in one of the toughest areas of a hard city Glasgows Gorbals. The saga of the life of the man who became famous as Gentle Johnny Ramensky began in the Lanarkshire of coal pits, clay mines, steelworks and brickworks in 1905, a time of conflict between immigrants from eastern Europe and native Scots, and ended two World Wars later in 1972. Between those dates, Johnny Ramensky led a life with the sort of highs and lows that are normally reserved for the movies.

Johnny Ramensky was undoubtedly a complex man. Part of him wanted a settled life, part of him wanted adventure, and he wrestled with these conflicting desires throughout his life. He was also well liked, as much by those in authority as those of the criminal classes. His chosen profession was safe blower and he was by far the most respected in his trade and the first name to be contacted if a criminal plan was being hatched that involved blowing open a safe. But his peacetime and wartime exploits also made him one of the most high-profile men in the land, a folk hero to many and a thorn in the flesh of authority. Being a criminal with a famous face plastered all over the newspapers is, however, not the most sensible way to keep out of jail, as Ramensky would find out. But it all contributed to the making of the man himself.

Despite its problems, there is no doubt that Johnny Ramensky relished his fame. After all, he was from a poor eastern European immigrant family, he had endured extreme poverty and he had made a name for himself against all the odds, even if it was a name not everyone would have wanted. He would have to endure years of incarceration for his crimes but, between these long stretches of time, were briefer interludes of adventure and excitement which really made him a household name. As well as becoming an astonishingly prolific jailbreaker whose latest exploits were avidly followed by the media, wartime service in the Commandos would set him apart from others and write his name into history as a legend, albeit a complex and highly flawed one.

The story of Johnny Ramensky begins with his early years in Glenboig, a time that shaped the boy and sowed the seeds of the man. He was born into poverty and deprivation and would later succumb to the easy money temptations of a criminal life partially perhaps to ease his familys grinding poverty in the infamous Gorbals in the early years of the twentieth century. But he was also motivated by a deep and constant thirst for adventure. In his youth, he had a chip on his shoulder about his antecedents and suffered racial taunts in an era less politically correct than today. His family roots were in far-off eastern Europe and he was frequently teased and taunted as a Pole though he was Lithuanian and a foreigner.

During his life, Ramensky would acquire something of a Robin Hood tag which was frequently used by some of the more lurid tabloids but was perhaps not completely accurate. In the Glasgow of his time robbing hoods were more of a speciality. But without a doubt he had some passing similarities to Robin of Sherwood. Johnny operated in the days when even among the toughest of the Glasgow slums there was something of a criminal code. Old ladies did not get bashed on the head for the meagre bags of shopping they were carting home from the local Co-op. Preferred targets for burglars and thieves were often businesses insured against loss, rather than private homes. And if a private home was the target it was more likely to belong to a businessman living in opulence in the suburbs than a struggling shipyard worker from a tenement close. He was, perhaps, a criminal of the old school.

Mind you, concentrating on tanning businesses rather than homes is not completely daft. Many a villain would tell you that it is a sound notion to steal from the well insured often you could go back and rob the same place again when it had reopened, by then tarted up and restocked with the aid of insurance money!

As well as the Robin Hood label there is a more exotic and slightly more realistic comparison in the Ramensky story with that of the French felon Henri Charrire, played by Steve McQueen in the Hollywood film of his memoir Papillon. Glasgow historian and novelist John Burrowes included a chapter on Gentle Johnny in his Great Glasgow Stories (Mainstream, 2000) and headlined it The Peterhead Papillon. Burrowes pointed out that Charrire, from the south of France, whose most sensational escape was from le du Diable, the notorious penal colony off the coast of South America, was born within months of Johnny in the early years of the twentieth century. They both died aged sixty-seven, within months of each other. Each man made five jailbreaks and both constantly tried to record their adventures in prison notebooks. Charrire had more success with his scribblings than Johnny, however.

Papillon first saw the light of day in the pleasant sunshine of the Ardche. Johnny was born in the less glamorous and less temperate surroundings of Glenboig. But in 1905 the Lanarkshire village at least had a commercial buzz and there was money-making going on in the place. Today it wears a resigned air of desolation, a village whose prosperity is visibly long gone. The air seems tainted with a whiff of better times past. Basically the village is now a crossroads, a pub and a post office and not too much else, though there is some little sign of life returning to the area with modern villas being built around the Farm Road area, in behind the pub, which is known as The Big Shop. The reason behind the odd name for these licensed premises is simple and logical. As you might expect of such an area, there was in its heyday more than one pub. The smaller Glenboig pub, now closed, was known, with admirable Scottish working-class humour, as The Wee Shop. Even the pub names tell a story.

Next page