CONTENTS

For Paul and my children

Lucy, Bee, and James

AUTHORS NOTE: FAMILIES AND TITLES

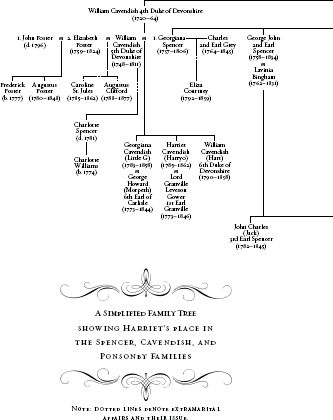

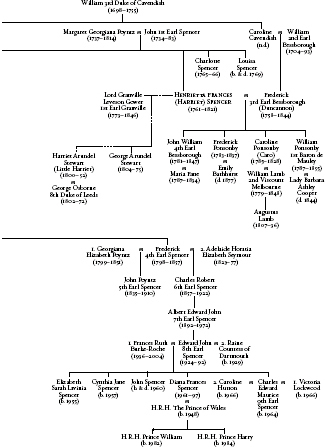

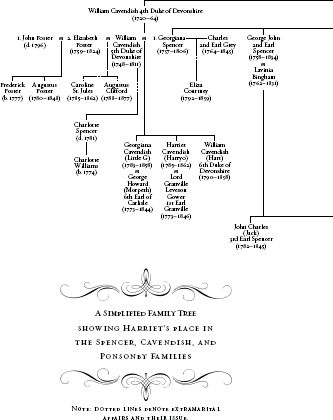

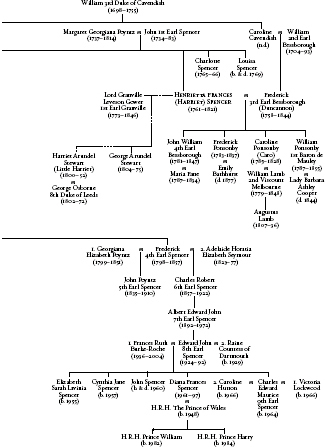

HARRIETS STORY involves three aristocratic families: the Spencers (Earls and Countesses Spencer), the Ponsonbys (Earls and Countesses of Bessborough), and the Cavendishes (Dukes and Duchesses of Devonshire). Their various titles, coupled with their habit of using the same name for various family members, can be highly confusing. In order to simplify matters I have often called family members by their nicknames. Nevertheless, the following may be helpful to those unused to the complexities of the peerage:

Earls and countesses (as in the Spencer and Bessborough families), along with most peers and peeresses apart from dukes and duchesses, are also called Lord X and Lady X.

Earls and countesses (as in the Spencer and Bessborough families), along with most peers and peeresses apart from dukes and duchesses, are also called Lord X and Lady X.

Eldest sons of dukes and earls take their fathers subsidiary title as a courtesy title (so-called because they are not entitled to sit in the House of Lords). Thus Earl Spencers eldest son is Viscount Althorp (or Lord Althorp); the Earl of Bessboroughs eldest son is Viscount Duncannon (or Lord Duncannon); and the Duke of Devonshires eldest son is Marquess of Hartington (or Lord Hartington).

Eldest sons of dukes and earls take their fathers subsidiary title as a courtesy title (so-called because they are not entitled to sit in the House of Lords). Thus Earl Spencers eldest son is Viscount Althorp (or Lord Althorp); the Earl of Bessboroughs eldest son is Viscount Duncannon (or Lord Duncannon); and the Duke of Devonshires eldest son is Marquess of Hartington (or Lord Hartington).

Daughters and younger sons of dukes are termed Lord X or Lady X (as in Lady Harriet Cavendish); daughters of earls are titled Lady X (as in Lady Caroline Ponsonby), while younger sons are titled the Honorable X (as in the Hon. Frederick Ponsonby).

Daughters and younger sons of dukes are termed Lord X or Lady X (as in Lady Harriet Cavendish); daughters of earls are titled Lady X (as in Lady Caroline Ponsonby), while younger sons are titled the Honorable X (as in the Hon. Frederick Ponsonby).

INTRODUCTION

ONE MORNING in late December, 1821, at 2 Cavendish Square, London, Sally, ladys maid to the late Countess of Bessborough, was called unexpectedly to her mistresss bedchamber. She answered the summons with a heavy heart, wondering who had called her and for what purpose. Her mistress had died in tragic circumstances in Italy a month earlier. Sally had served her for nearly thirty years; she had tended her in the last painful hours of her life, closed her eyes when she died, and accompanied her body on the long journey from Florence across wintry Europe to Derbyshire. The funeral had taken place only a week before, and she had yet to reconcile herself to the loss.

But when Sally entered the room the scene that greeted her pushed all such melancholy thoughts from her mind. A large fire had been lit and two of her mistresss sons stood waiting for her. Both seemed agitated and expectant as they confronted their final unwelcome dutythe task of sorting through their mothers correspondence. Harriet, as Lady Bessborough was known by everyone, had always kept her letters in her bedroom, crammed in drawers and her writing desk, some unsorted, others endorsed to be burned unread in the event of her death. They included potentially scandalous documents: letters from Harriets mother, Lady Spencer, and sister Georgiana, Duchess of Devonshire, discussing intimate mattersaffairs, pregnancies, illegitimate childrenand letters from lovers. What should her devoted sons do? Understandably, but sadly for later historians, they decided to repair the faade of respectability surrounding their mothers life. Having lit a large fire in the grate, they ordered the terrified Sally to say who [the letters] were from. Sally was reluctant, feeling this was a grave betrayal of the trust between herself and her mistress, but since she relied on the goodwill of the family for her pension she did as she was ordered. Thus as she identified each letter the vast majority were burned. The significance of this action was not lost upon the younger of the brothers, and tears poured down his cheeks. Thus was many valuable letters destroyed: the Dowager Lady Spencer and [Georgiana,] late Duchess of Devonshire with many other clever people. Georgianas only son was distraught when he discovered that his mothers letters had been burned rather than being returned to him, but Harriets eldest son was unrepentant in defense of his actions. There were so many painful subjects in that correspondence and so much that I knew it was wished to have destroyed,1 he declared.

Even when the desk was bare and all its contents reduced to ashes, the ordeal was not ended. Certain crucial letters were missing: Harriets most personal correspondence from the man who had been her lover and friend for almost half her life, a dashing diplomat twelve years her junior, Lord Granville Leveson Gower. Harriet had stored these intimate letters separately in a locked cedarwood box, which she took with her wherever she traveled. She had always promised Granville that they would be returned to him when she died, and presumably at some stage during her last illness she had had the presence of mind to give the box to Sally to hand on to Granville. As yet Sally had not carried out this request.

If such compromising material should fall into the wrong hands, her sons feared, the familys name might become a source of ridicule and gossip. Reputations and promising political careers might be jeopardized. The box had not been discovered among the possessions in Harriets room. Where was it? Fearing what was coming, Sally shook her head and refused to cooperate. Undeterred, the brothers called for the housemaid and repeated the question. The girl admitted that she had seen the box in Sallys room. Sally later recorded:

The poor box was brought forward; I had the key. The letters and all it contained was burned; I happened to have a few stray letters of hers to the duchess in my desk; looked them up and gave them to the Duke of Devonshire and the poor cedar box that has never lost its sweet perfume is still minealas how many hours, days, months of misery would the contents of that box have told, some of happiness no doubt but ended in bitter grief and enervating regrets for the days that was gone for ever.2

A fate that was only slightly more fortunate awaited the other half of this correspondencethe letters that Harriet had written to Granville. As a sparkling testimony to the life of one of the most fascinating women of the Regency age, as well as a record of enduring love, Granville had always treasured Harriets correspondence, and even after his marriage he had kept her letters carefully. A century later, when Granvilles daughter-in-law, Castalia, began deciphering Harriets notoriously difficult scrawl, she too was gripped by the letters. But, like the prudish brothers, she was also deeply embarrassed by the record of sexual indiscretion they contained.

Torn between terror of plunging the family into scandal and realization of the letters historical significance, Castalia edited out the most sensitive references to the affair and published them, intending to then burn the originals. According to a half-burned note still in the Leveson Gower family, she was dissuaded from following this drastic course and decided instead to deposit the letters in a bank. What course of action she actually followed remains uncertain; ever since Castalias publication of the Granville letters in 1914, the originals have been lost.

Next page

Earls and countesses (as in the Spencer and Bessborough families), along with most peers and peeresses apart from dukes and duchesses, are also called Lord X and Lady X.

Earls and countesses (as in the Spencer and Bessborough families), along with most peers and peeresses apart from dukes and duchesses, are also called Lord X and Lady X.