This book is rededicated to my children

Claudia and Raoul

in the hopes that it may in turn help them

to know and understand a grandfather

whom they, regrettably, could never meet.

He would have loved you both deeply.

Alexandra Kent

I am deeply indebted to countless people for the encouragement and help they have given me in my efforts in recent years to better understand my fathers life. I would like to express warm thanks to Richard King, author of 303 Polish Squadron Battle of Britain Diary , who was one of the first to set me off on a great journey of discovery. I received invaluable help and kindness from the staff of the Polish Institute and Sikorski Museum in London, in particular Krzysztof Barbarski and Wojtek Deluga, and from the curator of the RAF Museum at Hendon, Peter Devitt. Others who have tirelessly given me their time, assistance and stories along the way include Richard Kornicki, Chairman of the Polish Air Force Memorial Committee, and his wife Lepel; veteran fighter pilot Franciszek Kornicki and his wife Patience; veteran fighter pilot and author of First Light Geoffrey Wellum; Edward McManus of the Battle of Britain Historical Society; historians Peter Sikora and Andy Saunders; Witold Urbanowicz junior; Philip Feric-Methuen; the children of 303 Squadron Leader Ronald Kellett; and Danuta and Artur Bildziuk, Chairman of the Polish Airmens Association UK. Sincere thanks also to Rodney and Vicky Byles for everything.

I am also grateful to Mark Cazalet for the introduction to Tim, and to Tim Cazalet and Liz Razzell for their hospitality. An especially heartfelt thank-you to Tim for encouraging me to write and for the extraordinary generosity of giving me your mother, Janets, photograph album and books. I am also obliged to Tim for putting me in touch with his aunt, Patsy Rawlins, and cousin Rob Rawlins, who received me and all my questions with such interest. Thanks are also due to Tomasz Magierski for all the work on the film and for giving me the privilege of participating in such a fine production. I have met too many others on the course of this journey to include all their names but suffice it to say that I have been greeted with unfailing encouragement at the RAF Club in London, the Shoreham Aircraft Museum, RAF Biggin Hill, RAF Northolt and in Warsaw by those involved in organising the reunion of the Polish Air Force in 2012.

I wish too to express gratitude to my anthropology colleagues and mentors at Gothenburg University for many years of guidance. The insights into humanity that I gained under their tutelage have been invaluable in researching my own family. Warm thanks also to Kate Antonsson for her encouragement while I was writing the epilogue.

I would also like to take this opportunity to acknowledge all veterans and their families for everything that they have endured as a consequence of war.

Profound thanks also to my partner Jonas Persmark and my dear friend Harry Wright for their unstinting support, and to my brother Stuart, my sister Joanna and my sister-in-law Linda for sharing with me their memories of a man who lives on in our hearts.

Finally, I wish to thank my parents.

Alexandra Kent

Contents

by Alexandra Kent

Sunday Times , 19 January 1941, Not a Poet:

A young man of twenty-five stood beside two or three Polish airmen last week and received a decoration for gallantry from the Polish Foreign Minister. He was slim, with fine features and delicate hands. His face had little colour, and only a curious hardness about the mouth denied the idea that he might have been a poet or an artist.

A year before the war he came from Winnipeg and took a permanent commission in the R.A.F. When the balloon barrage was being prepared it became necessary to test the exact effect that contact with the cables would have on aeroplanes. The young Canadian volunteered and crashed the cables eighteen times. For that he was awarded the Air Force Cross. Later in the war he was given command of the Polish Squadron formed here after that countrys collapse. They were so brave, he said, that you didnt dare to show a sign of fear even if your heart was in your mouth. Under his leadership the bag of the Polish Squadron reached amazing proportions. He was decorated with the D.F.C.

Now he has been given another command, but Poland has added her honours to ours. His name is Squadron-Leader Kent, and from his appearance he might have been a poet but I would hate to be the German looking at those eyes and mouth behind a gun.

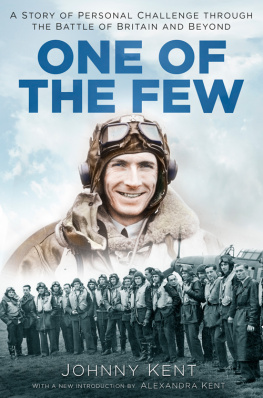

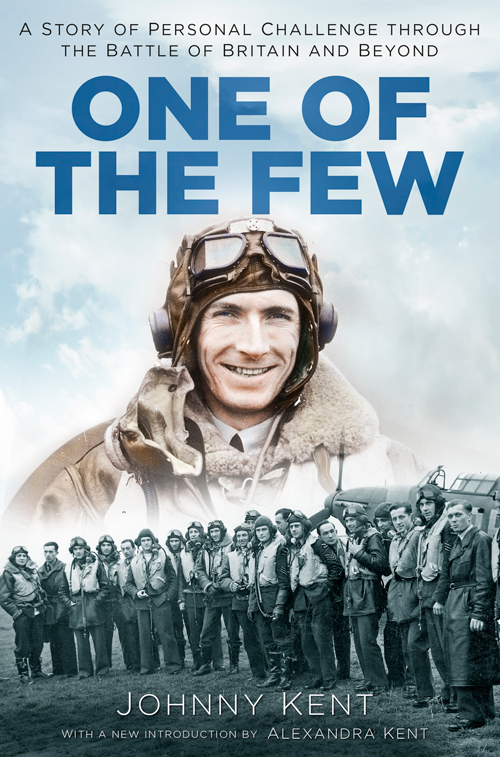

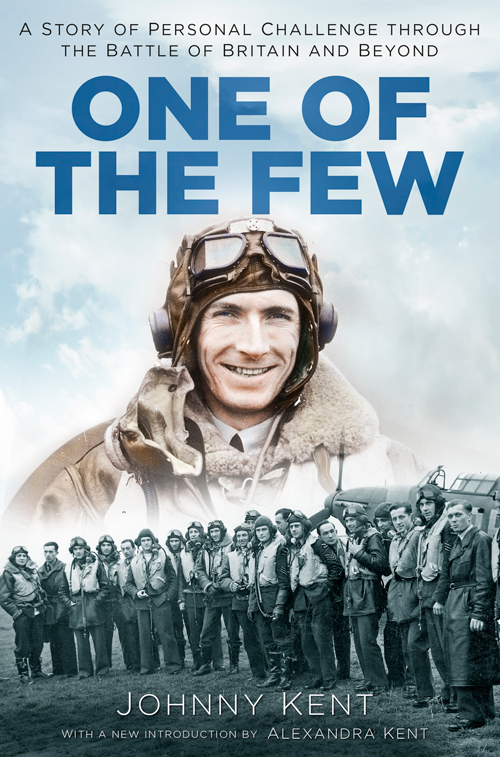

Many of those I have met who have read my fathers memoirs, One of the Few , have asked me the same question: What was he really like? This was not easy for me to answer because my memories of him are from childhood and the man I knew had retired from the RAF before I was born. When his memoirs were published, I was 13 years old. I read them and found the voice that spoke from the pages quite different from the familiar voice of the father I knew. But, as Shakespeare so famously wrote, one man in his time plays many parts. In this introductory chapter and the epilogue that follows at the end of his memoirs, I shall bring together some of the different parts he played and place the story he told of his life into a broader context. In this way, I hope to give a fuller picture of what he was like.

One of the Few was very much of its time, and the Boys Own genre in which it was written was what its audience would have expected. I imagine that if fighter pilots like my father, who were virtually idolised as modern-day knights, had exposed self-doubt or frailty in their stories they might not have been well received. However, as the veterans stories become history, I believe it is worth re-examining the old stereotypes of gallant heroes in order to understand these men with a fuller sense of humanity.

Beyond my fathers memoirs, I find a complex character whose life was marked by powerful contradictions. There are many things about him that betray, if not a poet, then a person of aesthetic sensibility who valued solitude and peace. He may have been born to fly, and he certainly sought to excel, but there is nothing to suggest aggressiveness. However, coming of age in such brutal times meant his passion for flying and pursuit of excellence were channelled into the cruel business of killing. However noble the cause, slaying another human being, particularly in one-to-one duels, must impact the soul in ways that defy expression. Even before the war, my father demonstrated an impressive ability to keep his nerve in his test-flying exploits. But this does not mean he was fearless. As a leader who was responsible for his comrades in battle some of whom proved to be more fearless than he he must have been under inconceivable pressure to maintain morale by masking his feelings, perhaps even from himself.

There was also the contrast between the strict, almost ascetic discipline of service life and the raucous evenings at pubs and nightclubs, where alcohol played an important role in both sharing and deadening heightened sensitivities.

He writes, too, of the sacrifice his parents made for him and yet, perhaps driven to excel in the RAF as a way of thanking them, he deprived them of the presence of their only child. He left home at the tender age of 20 to embark on a hazardous career on the other side of the world, returning home only twice before his mother died in 1944.

There is also the ambiguity of his role in the RAF; his British heritage and Canadian upbringing meant he was part insider, adept at reproducing British and RAF attitudes and manners, but also part outsider, a condition that was influential in his relationship to the Polish airmen he came to lead. The challenge of gaining acceptance in English society is a point I return to in the epilogue.

Next page