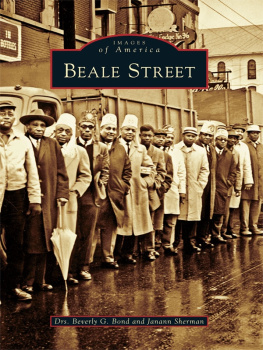

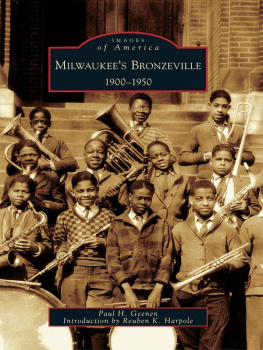

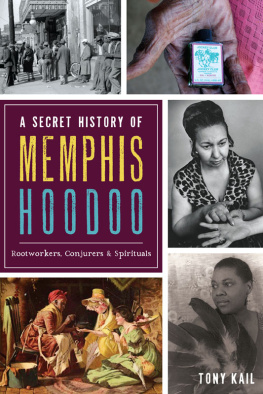

We would like to thank the many individuals and institutions who provided invaluable assistance in helping us locate images for this book. Although Beale Street has been part of the lives of countless black and white Memphians, finding photographs that open a window on this vibrant thoroughfare is not an easy task. The work of early photographers like Earl Williams, the Hooks Brothers, and the legendary Ernest Withers is scattered in collections that are not as accessible to scholars as one might think. We owe a great debt to Dr. Jim Johnson, Patrick ODaniel, and Gena Cordell at the Memphis Room of Benjamin L. Hooks Public Library; Margaret McNutt and Ronald Brister at the Pink Palace (Memphis Museum System); and Ed Frank in the Mississippi Valley Collection at the University of Memphiss Ned McWherter Library. We are also indebted to the many talented but often little-known photographers whose images of Beale Street are included in these collections, particularly the staff photographers for the Commercial Appeal (Sam Melhorn, James Shearin, Vernon Matthews, Bob Williams, Barney Sellers, and Lloyd Dinkins) and the Press Scimitar (Glenn Patterson, James Reid, William Leaptrott, Ken Ross, Tom Barber, Paul Dagys, Jack Cantrell, John George, Ken Ross, and William Ellis). Our University of Memphis colleagues, Dr. Douglas Cupples and Tommy Towery, also contributed previously unpublished images of 1960s Beale Street. Mr. Juan Self of Self-Tucker Architects provided information on the first Universal Life Insurance Company building, and Dr. Benjamin L. Hooks allowed us to use several Hooks Brothers photographs from the Memphis Room collection. The Riverfront Redevelopment Corporation provided the last two images in this book of the vision for Beale Street in the 21st century. We reserve a special thank you for William Bearden and Jeraldine Sanderlin. Willy not only contributed pictureshe came to our rescue, helped us figure out how to organize this project, and shared photographs and knowledge of Beale Streets blues music tradition. Sanderlin provided recollections of Beale Street in the 1940s and 1950s.

Lastly we would like to acknowledge the patience and support of our families and friends, especially Geraldus Fuzz Bond and the late Charles Charlie Shermanstill the wind beneath our wings.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Bearden, William. Memphis Blues: Birthplace of a Music Tradition . Charleston, SC: Arcadia Publishing Company, 2006.

Beifuss, Joan Turner. At the River I Stand . Memphis: St. Lukes Press, 1990.

Biles, Roger. Memphis in the Great Depression . Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1986.

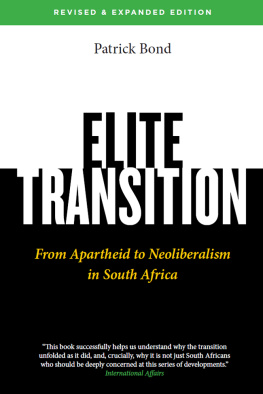

Bond, Beverly G. and Janann Sherman. Memphis in Black and White . Charleston, SC: Arcadia Publishing Company, 2003.

Cantor, Louis. Wheelin on Beale . New York: Pharos Books, 1992.

Capers, Gerald. The Biography of a River Town . New York: Vanguard, 1966.

Church, Roberta and Ronald Walter; Charles W. Crawford, ed. Nineteenth Century Memphis Families of Color 18501900 . Memphis: Murdock Printing Company, 1987.

Coppock, Helen M. and Charles W. Crawford, eds. Paul R. Coppocks Mid-South, Vol. IVol. IV. Memphis: Paul R. Coppock Publication Trust, 19851994.

Gordon, Robert. It Came from Memphis . Boston: Faber and Faber, 1995.

Hamilton, G. P. The Bright Side of Memphis . Memphis: G. P. Hamilton, 1908.

Kirby, Edward. Memories of Beale Street Memphis: Where It All Began . Memphis: Penny Pincher Sales, 1979.

Lamon, Lester. Blacks in Tennessee 17911970 . Knoxville: The University of Tennessee Press, 1981.

Lauderdale, Vance. Ask Vance . Memphis: Bluff City Books, 2003.

Lee, George W. Beale Street: Where the Blues Began . New York: Robert O. Ballow, 1934.

Lewis, Selma S. and Marjean G. Kremer. The Angel of Beale Street: A Biography of Julia Ann Hooks . Memphis: St. Lukes Press, 1986.

Magness, Perre. Good Abode: Nineteenth Century Architecture in Memphis and Shelby County, Tennessee . Memphis: The Junior League of Memphis, Inc., 1983.

McKee, Margaret and Fred Chisenhall. Beale Black and Blue: Life and Music on Black Americas Main Street . Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1981.

Miller, William D. Memphis During the Progressive Era . Memphis: Memphis State University Press, 1957.

Raichelson, Richard. Beale Street Talks . Memphis: Arcadia Records, 1994.

Sigafoos, Robert A. Cotton Row to Beale Street: A Business History of Memphis . Memphis: Memphis State University Press, 1979.

Tucker, David M. Lieutenant Lee of Beale Street . Nashville: Vanderbilt University Press, 1971.

Walk, Joe. A History of African-Americans in Memphis Government . Self-published, 1996.

Wrenn, Lynette Boney. Crisis and Commission Government in Memphis . Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1998.

Find more books like this at

www.imagesofamerica.com

Search for your hometown history, your old

stomping grounds, and even your favorite sports team.

Two

THE MAIN STREET OF NEGRO AMERICA

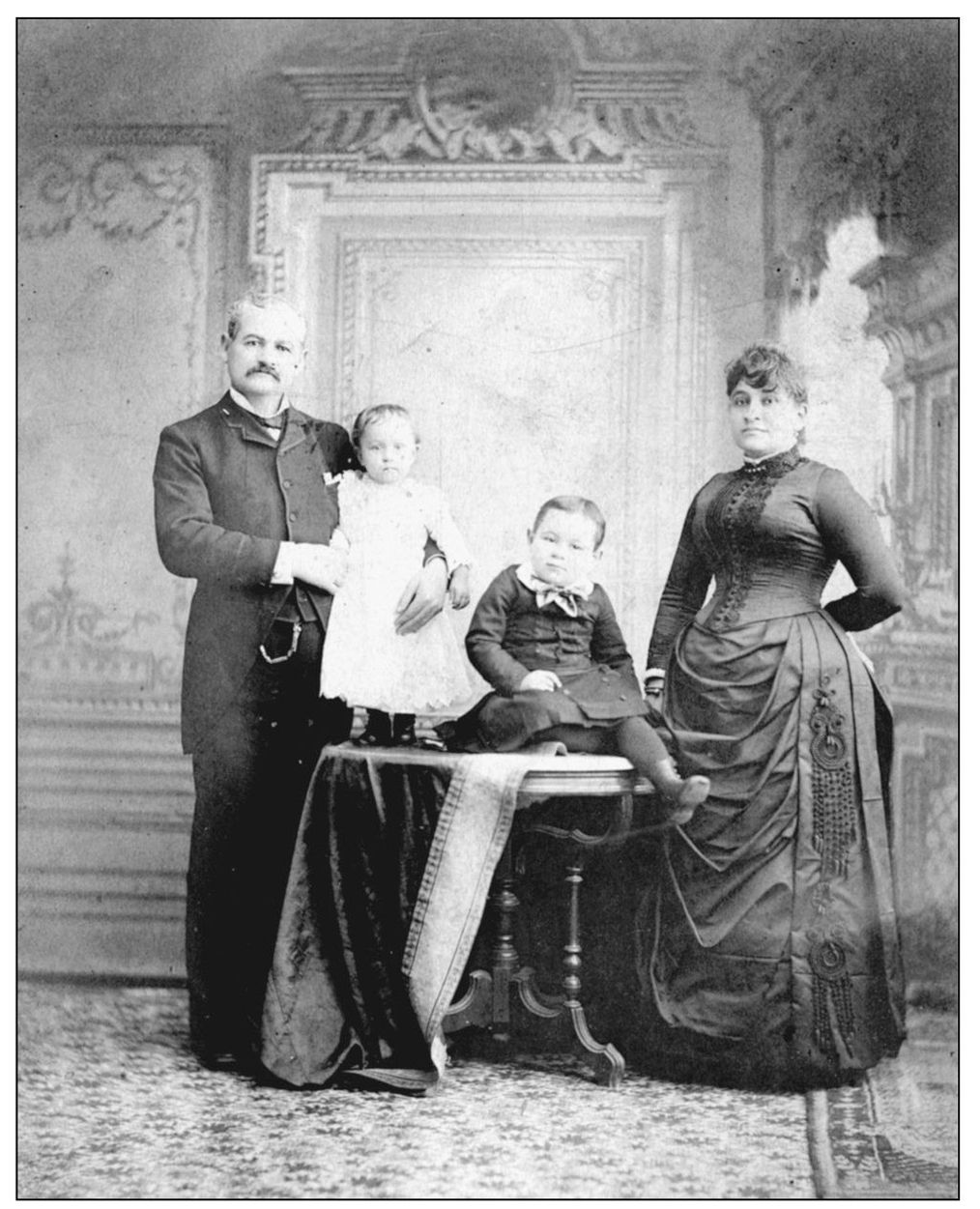

Few African Americans owned property on Beale Street, but many rented residential or occupational spaces in buildings on the street or on neighboring streets and alleys. Robert (Bob) and Anna Wright Church were exceptions to this rule. In the late 1800s, Church made his fortune in real estate, saloons, and billiard halls in the Beale Street area. He paid $1,000 to purchase Bond No. 1 to help the city regain its charter in the 1890s. Anna Wright Church, one of the first generation of African American teachers in the city, was a prominent figure in African American womens cultural, literary, and social organizations. (Mississippi Valley Collection.)

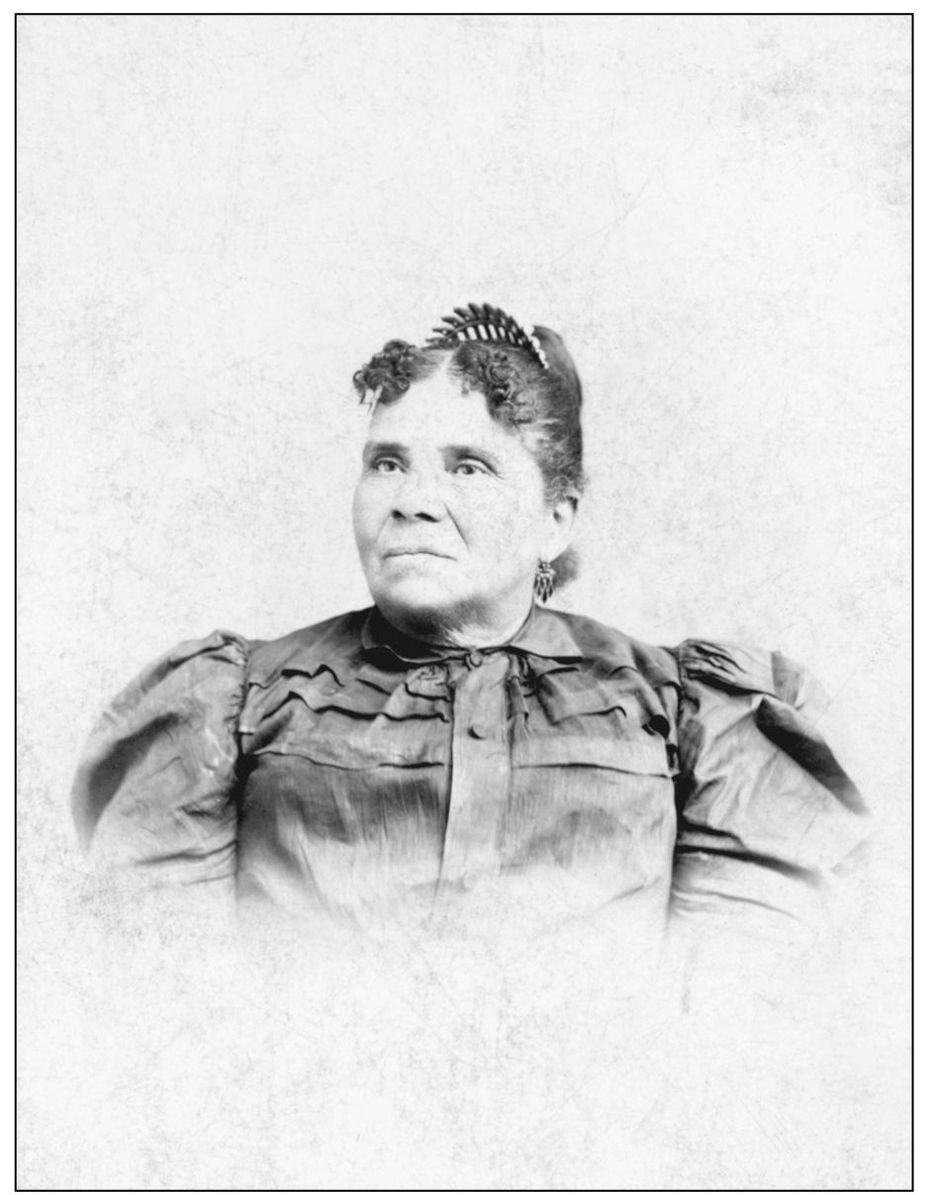

Born in Memphis before the Civil War, Martha Ferguson operated a hand laundry business that specialized in fine linen, lace, and silk. Like many other African American women, she used the income from this profitable business to support her family and to educate her daughter, Ida, who attended a school in Antioch, Ohio, with Anna Wright and also taught in the citys black schools. (Mississippi Valley Collection.)

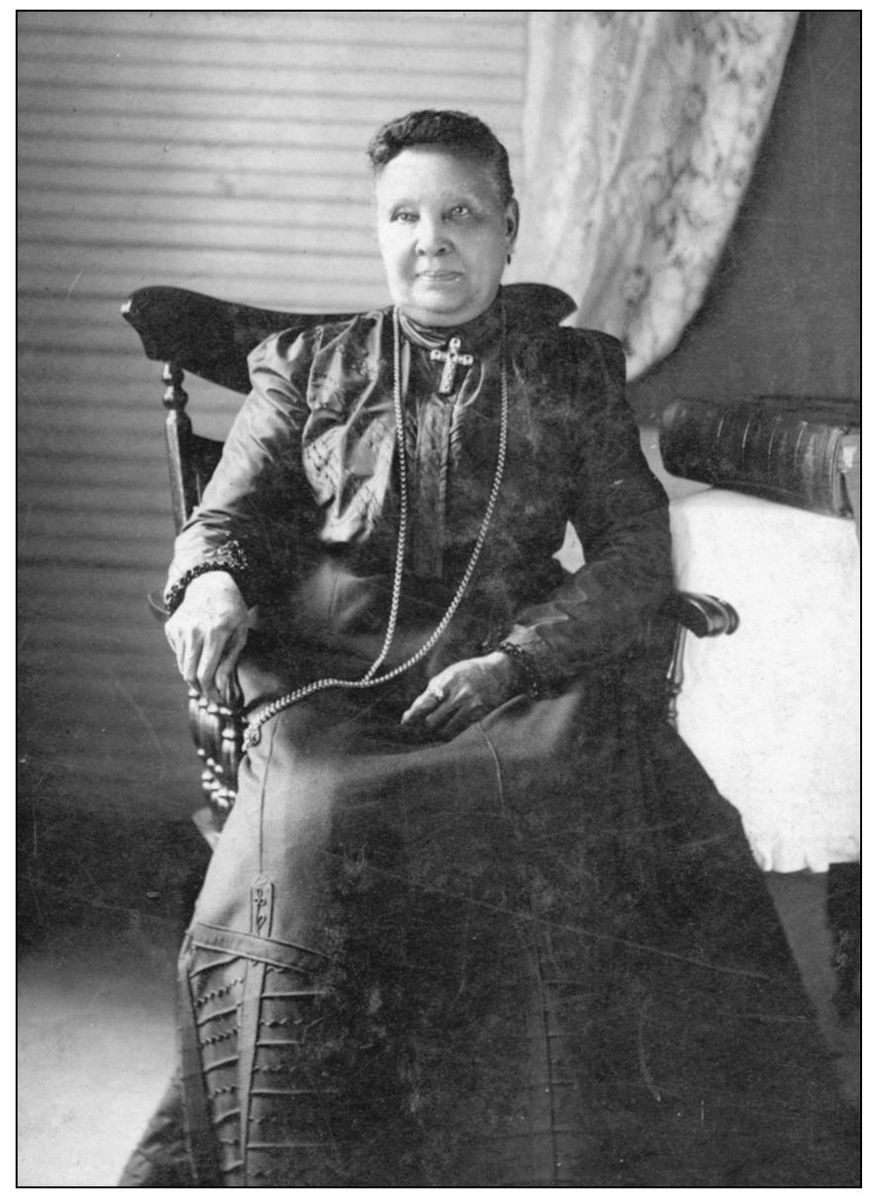

Dora Clouston was the wife of Joseph Clouston, an antebellum free black man and one of a small number of African Americans who owned property in the Beale Street neighborhood before and after the Civil War. Joseph Clouston also operated a grocery store and barbershop at 145 Beale Street in the late 1800s. (Mississippi Valley Collection.)

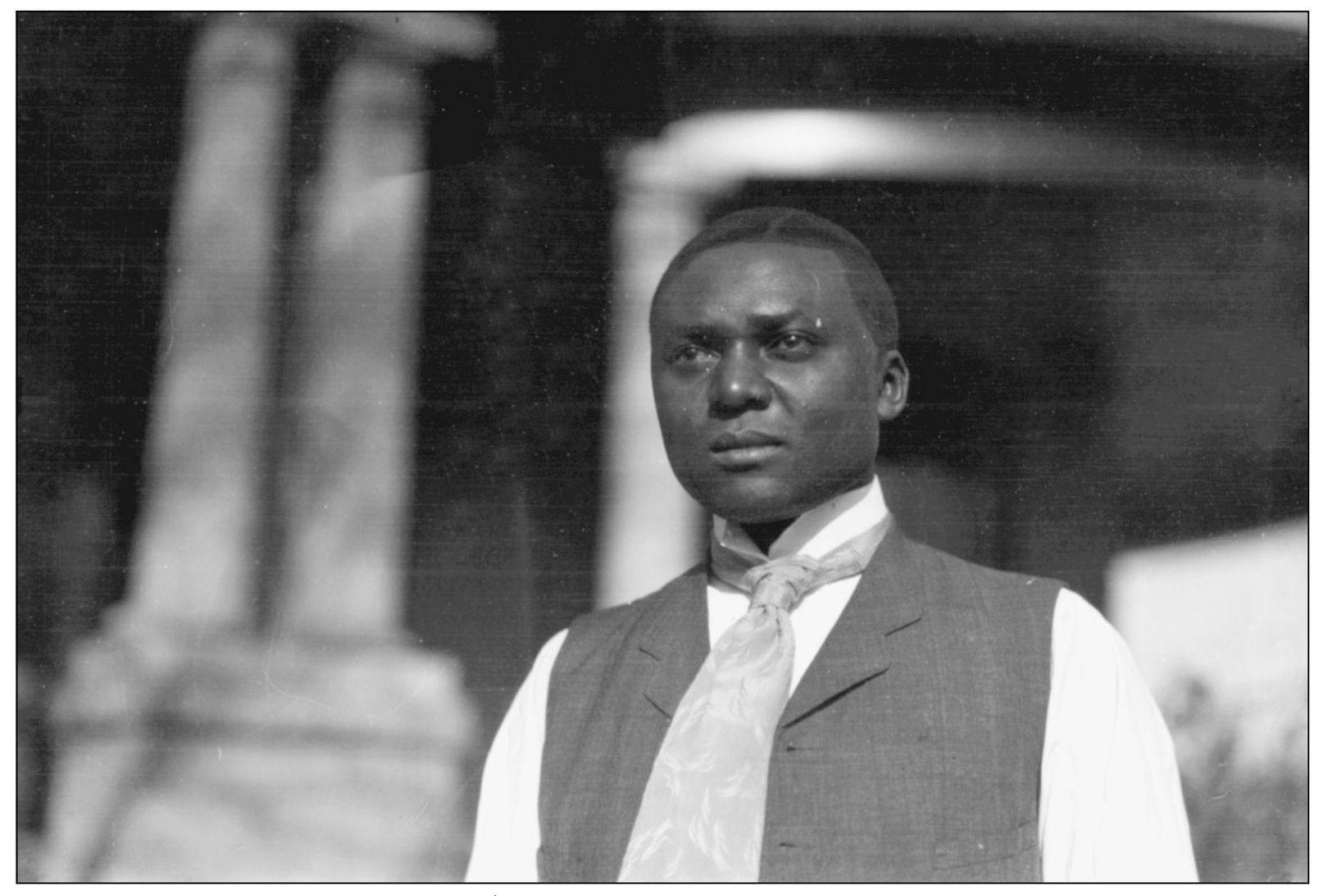

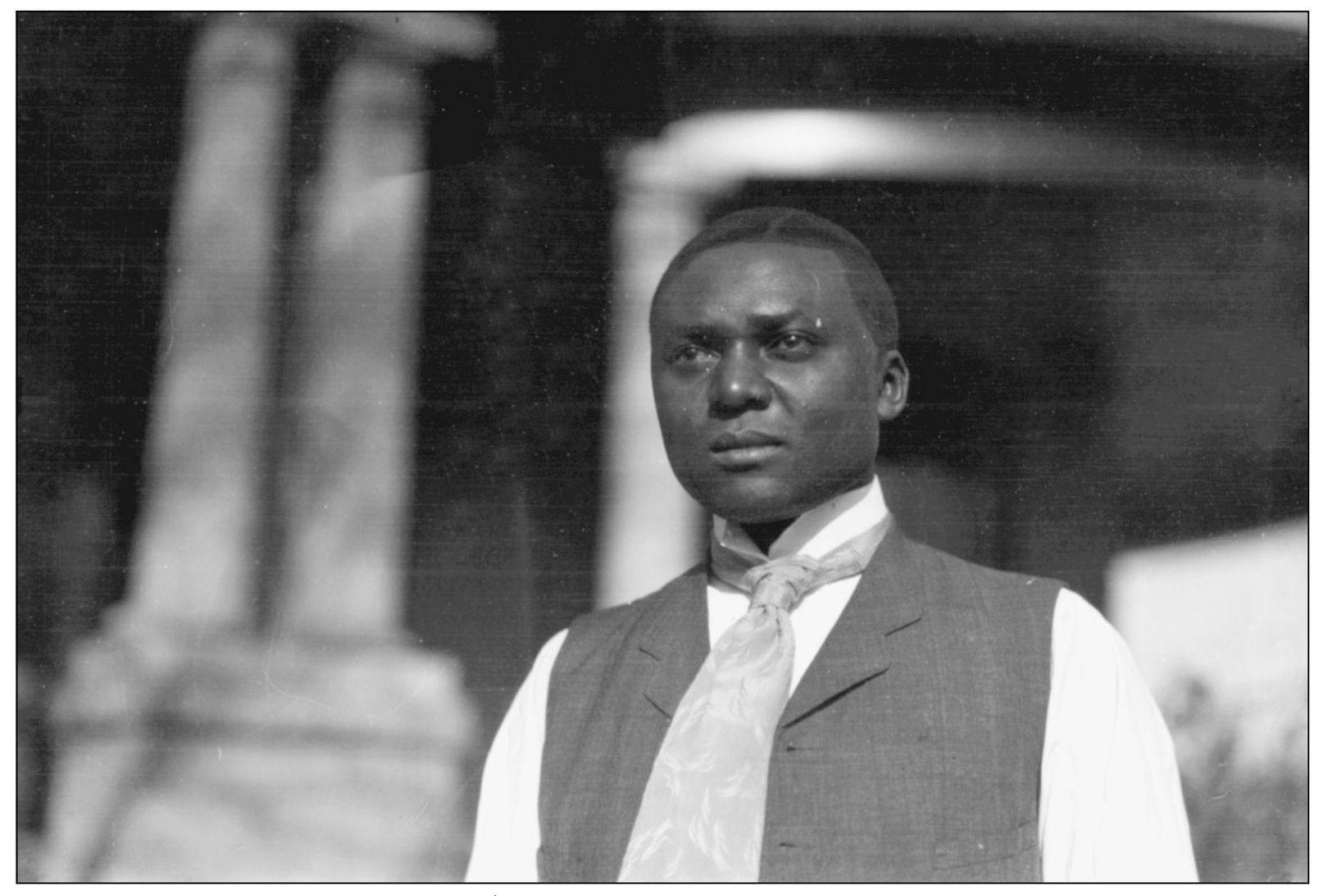

Most African Americans in Memphis were working-class people, many of whom migrated to the city from the Mississippi Delta or eastern Arkansas. In 1860, African Americans were only 17 percent of Memphiss population. Ten years later, in the aftermath of the Civil War and Reconstruction, blacks were nearly 39 percent of the citys population; by 1890, in the aftermath of yellow fever epidemics and rural migrations, blacks were 44 percent of the total population. Most black men worked as domestic servants or as laborers in the citys cotton-related industries, while most black women worked as cooks, domestic servants, midwives, nurses or laundresses. As writer George W. Lee noted, Saturday night [Beale Street] belongs to the cooks, maids, houseboys and factory hands, who enjoy the streets theaters, poolrooms, or juke joints. But Sunday was also the time that many of the same people spent in the churches in the Beale Street neighborhood. Lizzie Rollin and Andrew, shown in these two photographs from the collection of photographer Abraham Frank, were servants in the Frank household and most likely weekend visitors to Beale Street establishments. (Mississippi Valley Collection.)