One

COMMERCIAL DEVELOPMENT THIS LITTLE LIGHT OF MINE

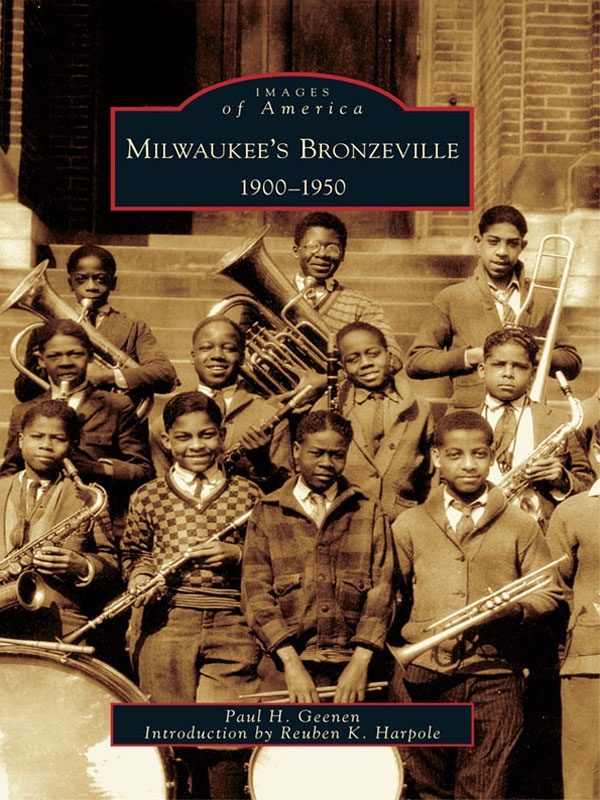

Between 1915 and 1932, the increasing flow of poor migrants coming from the South needed rooming houses, inexpensive cafes, and a place to get a haircut. They patronized the African Americanowned barbershops, restaurants, funeral homes, nightclubs, and taverns on Walnut Street, sometimes called Chocolate Boulevard by the unenlightened.

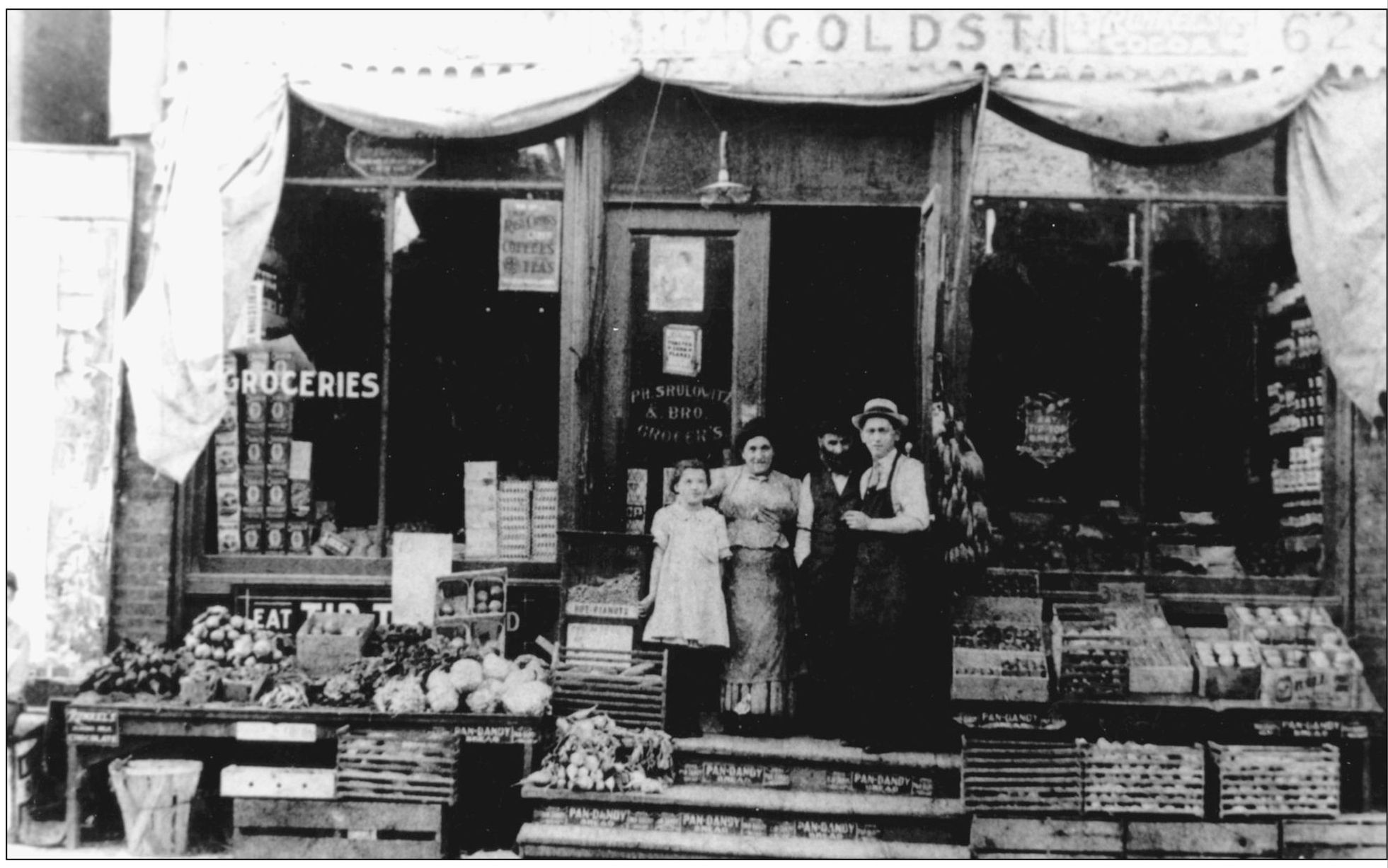

In the 1920s and 1930s, many Russian Orthodox and Reformed Jewish families also made their homes in the Walnut Street business district, establishing synagogues and such businesses as grocery stores, a bakery, a drugstore, and a deli. In the 1940s, however, Jewish residents of Bronzeville. began moving west to Sherman Boulevard and were replaced by African Americans.

Most African American businesses were started with very little capital and supported by overtime work at a foundry by the men and extra domestic work taken on by the women. After coming to Milwaukee in 1924, Eugene Burns Mathews saved for 22 years before starting his Eighth Street Barbershop. He worked two shifts at the Falk Corporation, and later at A. O. Smith, then, with a loan from Columbia Savings and Loan in 1946, opened his first barbershop inside a drugstore at Eighth and Lloyd Streets.

Londy Cox, after a full days work at Crucible Foundry, worked at his Northside Sandwich Shop until it closed at midnight. His daughter, Harriet Spicer (nee Cox), opened the restaurant after school, doing her homework whenever business was slow. She says she was never late with her homework because she could not afford to stay after school!

Anthony Josey, editor of the Wisconsin Enterprise Blade , wrote many editorials advocating the support of African American businesses, believing they would create jobs for the youth of the community and present a viable alternative to the employment discrimination African Americans were encountering elsewhere.

Urban Renewal and the clearance of land for the freeway system in the 1950s and 1960s sounded the death knell for these African American businesses. The Hillside Redevelopment Project cleared the heart of the African American business district, and although some businesses relocated, most did not survive over the long run.

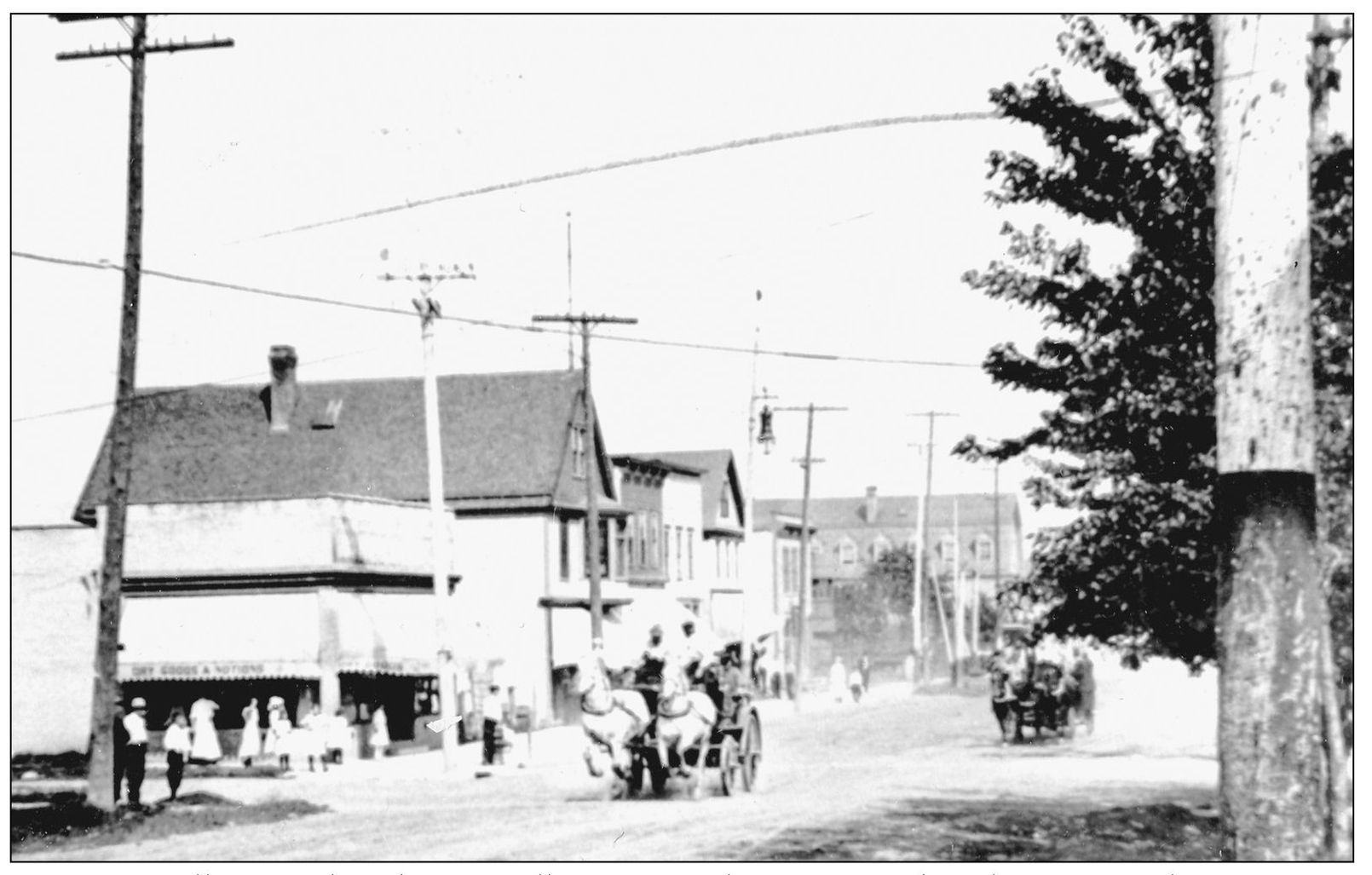

A pair of galloping white horses pulls a wagon down unpaved Walnut Street, before it was widened, while pedestrians wait to cross the street sometime during the early 1900s. There were 980 African Americans living in Milwaukee in 1910. (Photograph courtesy of Milwaukee Jewish Historical Society.)

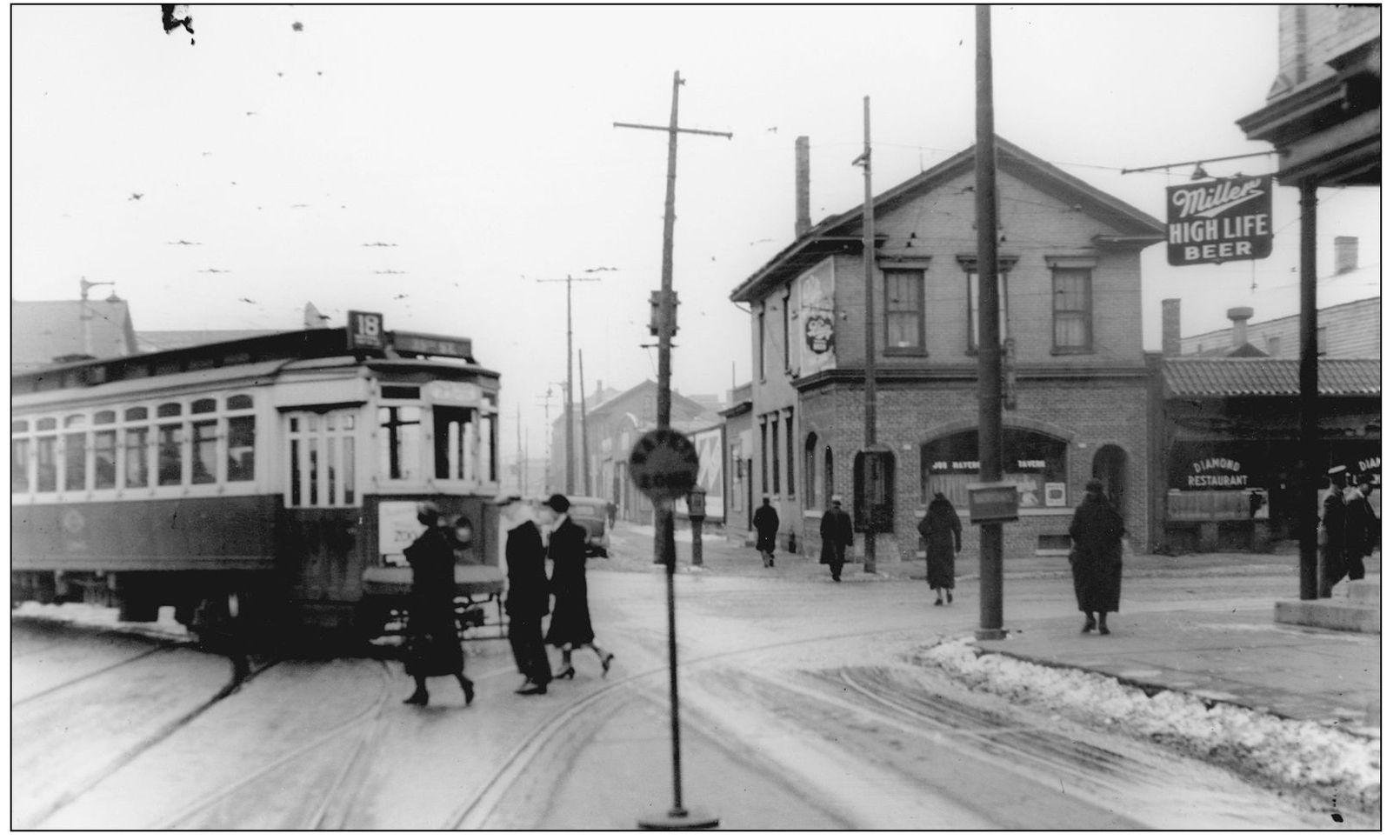

A streetcar heads south on Third Street after crossing Walnut Street on a chilly winter morning in this undated photograph. The Milwaukee County lines were thought of as being one of the best systems in the country. Quiet trolleys ran every 10 minutes, taking passengers to virtually anywhere in the Milwaukee County and running during the night for the second- and third-shift workers. (Photograph courtesy of Historic Photograph Collection/Milwaukee Public Library.)

The Surlow (Srulouitz) family displays a fine selection of fresh vegetables and eggs sometime in the early 1920s. Corner stores were an important part of life in Bronzeville, If our parents did not have any money, we still got what we needed from the store, one former resident said. We would pick up what we needed and be told tell your Ma or Dad to pay me next week. Starting in 1910, Russian Jews from Eastern Europe immigrated to Bronzeville, living in the neighborhood with African American immigrants from the South. This began a relationship in Milwaukee between these two ethnic groups that continued through the 1960s civil rights movement to today. (Photograph courtesy of Milwaukee Jewish Historical Society.)

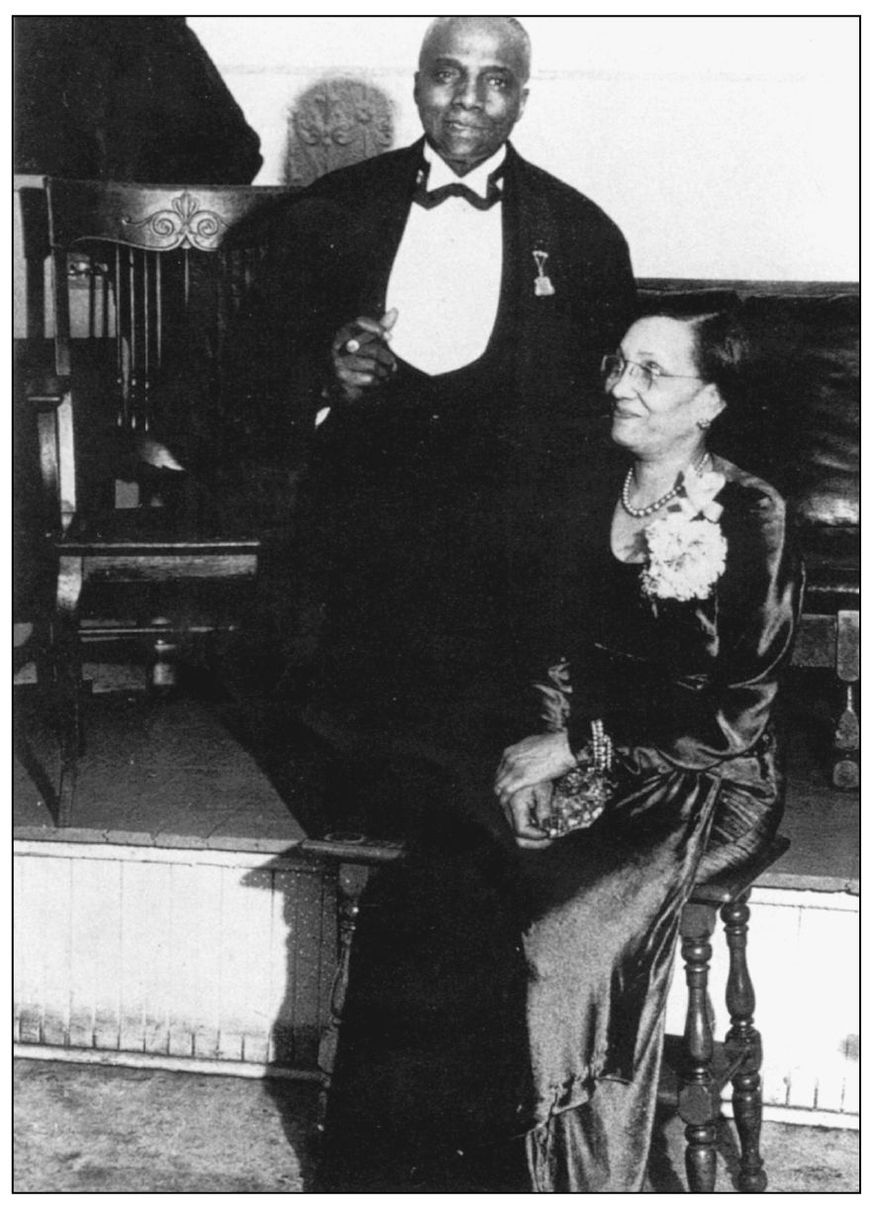

Anthony Josey was born in Augusta, Georgia, graduated from Atlanta University, and went to the University Of Wisconsin Law School. In 1925, he moved to Milwaukee and published the Wisconsin Enterprise Blade . As editor of the Wisconsin Enterprise Blade , Josey was a loud voice on issues that affected African American lives. (Photograph courtesy of University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee.)

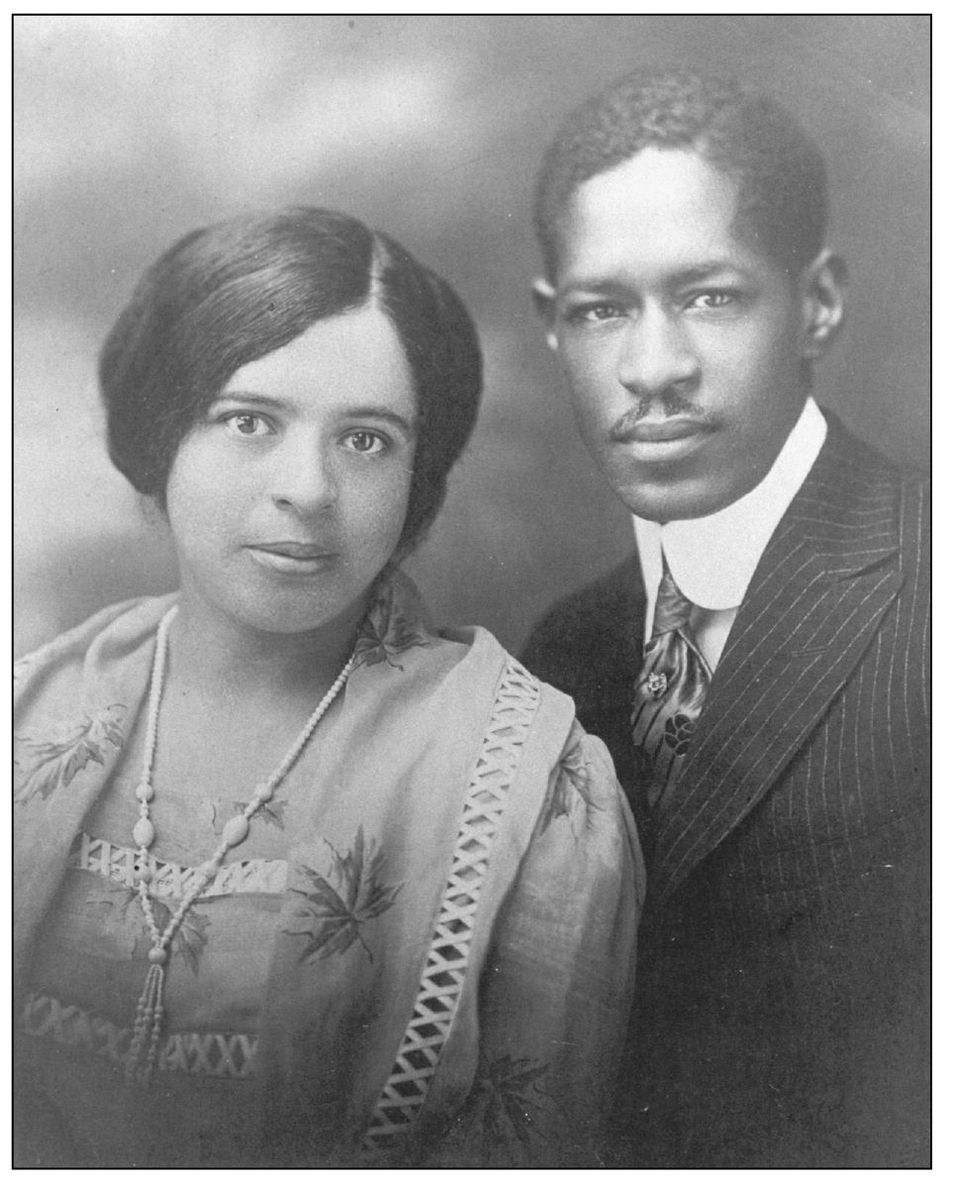

Clarence and Cleopatra Johnson opened their tailoring shop in 1921, working closely together as partners and creating the first successful black business in Milwaukee. Clarence was one of the founding officers of the Columbia Savings and Loan, which opened in January 1925. Clarence Johnson is credited as being one of the founders of the Booker T. Washington YMCA on Eighth and Walnut Streets. (Photograph courtesy of Wisconsin Black Historical Society/Museum.)

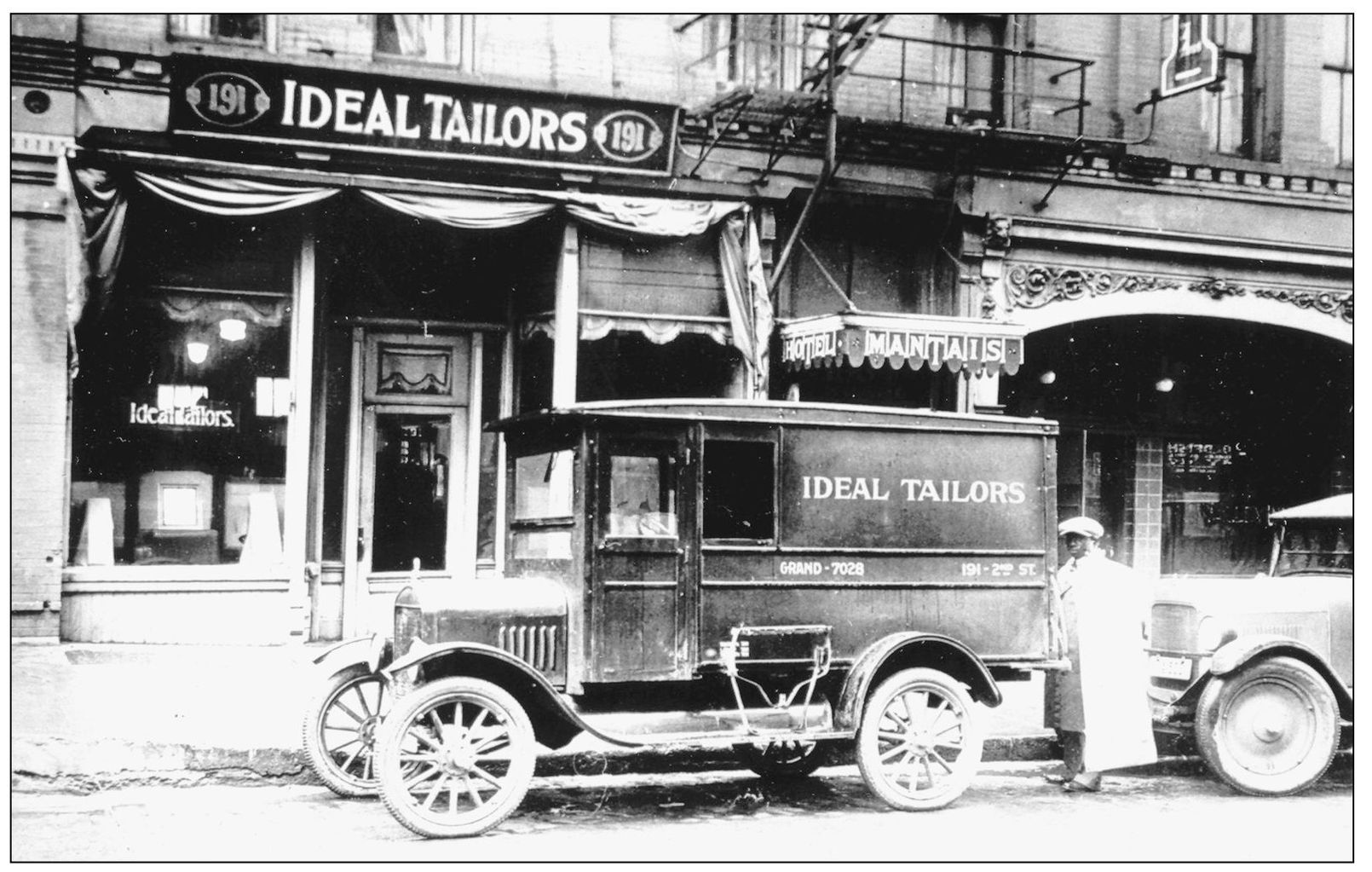

The Ideal Tailor Shop opened in 1921 when business dropped in the foundry in Beloit where Clarence was working. The Johnsons had difficulty getting white property owners to rent to them and initially leased the building shown here through a white intermediary. (Photograph courtesy of Wisconsin Black Historical Society/Museum.)