C ONTENTS

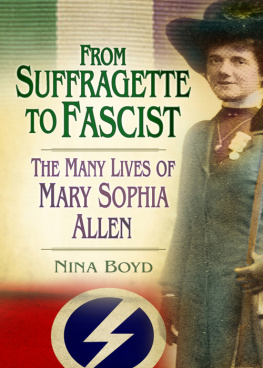

I first came across Mary Sophia Allen on a rainy day in Ripon, North Yorkshire, in 2001. Caught by a sudden downpour I took refuge in the nearby Prison and Police Museum. In a room full of helmets, whistles, handcuffs, police notebooks, dominated by a waxwork sergeant, the most interesting item was a postcard in a rack.

I took my postcard home and made a quick internet search of its subject. Mary Allen was a mystery: a fighter for womens rights and an unsung hero of policing, who transformed herself into a political virago.

She was difficult to research, having been unmarried and childless; but distant relatives all over the world dug out memories and photographs. I am indebted to them all.

I cannot hope to rescue the reputation that Mary lost by her own wilfulness and folly. But I do believe that this opinionated, infuriating woman should not be entirely forgotten.

My thanks to the descendants of Marys siblings: Penny Gill and Rosemary Frouws in South Africa, and Margaret Bateman in Ireland; and to Vicky Tagart, who provided copies of family letters.

Also to the people at various organisations who answered requests for information, including The League of Women Voters, Buffalo, Niagara; Lynda James, Bereavement Services Advisor, Croydon; and the Public Record Office; and to the generous people who have given me additional information, including Pat Benham, Val Jackson, Joan Lock and Paul Ashdown.

And to those who read early attempts at a manuscript: Jill Liddington, Carola Luther and Andrew Biswell; Alan Henness, who helped me with my website; and my own supportive family, particularly John Bosley, Jacqueline Bosley, Maria Fernandez, Lynda Hulou, and Eleanor, Bill and Tom Boddington.

| ASL | Artists Suffrage League |

| BJN | British Journal of Nursing |

| CLAC | Criminal Law Amendment Committee |

| DORA | Defence of the Realm Act |

| FANY | First Aid Nursing Yeomanry |

| GWR | Great Western Railway |

| ILP | Independent Labour Party |

| IRA | Irish Republican Army |

| MWPP | Metropolitan Women Police Patrols |

| NUWSS | National Union of Womens Suffrage Societies |

| NUWW | National Union of Women Workers |

| NVA | National Vigilance Association |

| PRO | Public Record Office |

| WAS | Womens Auxiliary Service |

| WFL | Womens Freedom League |

| WPP | Women Police Patrols |

| WPS | Womens Police Service |

| WPV | Women Police Volunteers |

| WSPU | Womens Social and Political Union |

| WVP | Women Voluntary Patrols |

In 1915, Mary Allen and her lover, Margaret Damer Dawson, had their hair cropped and posed for a photographer. They wore the uniforms they had designed for themselves as leaders of a newly formed womens police service: military-style peaked caps, long greatcoats, tightly knotted ties and highly polished jackboots.

They are tall women, standing side by side in a formal pose, their feet positioned awkwardly at right angles. They take their roles as pioneer policewomen seriously; but at the same time, the nature of their relationship is apparent from the way they stand half-turned towards one another, the fingers of their white gloves intertwined. There is a hint of a smile on Marys face.

They had known each other for only a few months, but Margaret, who had no reason to know that she would only live another five years, had already made a will, leaving her substantial fortune to Mary.

In the seven years since she had been banished from her fathers comfortable home, Mary had observed the working of the law from all sides: as a suffragette she had been imprisoned three times and forcibly fed while on hunger strike; later she accompanied a deputation of members of Parliament on an inspection of conditions in Holloway Jail; and she became second-in-command to Margaret Damer Dawson in the first womens police service. She took over as commandant of the Womens Police Service after the death of Margaret.

Mary was a constant irritant to the Metropolitan Police Force which has effectively erased her from their history of womens policing. She became well known in all corners of the world as the leading British policewoman, while the authorities at home no longer recognised her as any sort of policewoman. Curiously, she was asked in 1923 to advise the government on policing the post-First World War British occupation of Germany,long after she had been instructed by the same government to disband her police force.

After a meeting with Hitler, Mary embraced fascism and supported Oswald Mosley. She came close to being interned for her political activities in the 1940s. It may be that only her growing eccentricity saved her from detention.

Mary Allens story is extraordinary. She was a woman of whom it would be impossible for any liberal-minded reader to approve, but at the same time she inspired deep affection and loyalty from friends and family throughout her long and eventful life.

1

A B ENEVOLENT

D ICTATORSHIP

We tend to remember the house we grew up in as being much bigger than it actually was; but Mary Allens childhood home was certainly substantial by modern standards. She was part of a household of two parents, ten children, and assorted nannies, governesses and servants, and they were not cramped for space:

As we grew older, boys and girls rode a velocipede around the garden paths, and on rainy days (forbidden joy!) even along the corridors. A velocipede! The name itself was an enchantment. Can any later invention provide a more fascinating suggestion of speed produced by short gyrating legs?

Little is known of Marys childhood. She was always reticent about the details of her private life, in marked contrast with her partiality to self-advertisement in the public sphere. In her first volume of autobiography, The Pioneer Policewoman, she claims that she was a very delicate child, educated almost entirely at home, and denied all the training in outdoor sports of the robust modern girl. Increased mental activity may possibly have been the result of this intolerable physical restraint. Yet it was a busy, active childhood, fondly remembered fifty years later in A Woman at the Cross Roads, when Victorian values and the virtues of discipline and hard work had been replaced by what Mary perceived as dangerous libertarianism. We invented games, made things, carpentered, jig-sawed, dug in the garden. (p.15) There were outings to a pantomime at Christmas, and three or four visits a year to the theatre, either as a birthday treat or as a reward for good conduct. (p.30) She describes a series of governesses, of varying quality and ability, but all respected and obeyed by their charges.

We might expect a childhood as apparently happy as Mary Allens to be recounted in more detail by a woman who wrote three autobiographies; but in none of them does she even tell us the first names of her brothers and sisters, or recall anecdotes from her earliest years. All she tells us is that her large family was not unusual, and that nannies were important figures, more present in the childrens lives than their parents:

From the age of two, or even earlier, we recognised a benevolent dictatorship a discipline firm but not harsh (in spite of novels that make the exceptional seem the usual state of affairs). It was a brave child who would dare defy Nannie! In looking back, it seems to me that we were very rarely punished. Not to be permitted to go down-stairs to join our parents in the real dining-room, to say good night, was a bitter humiliation. (pp.1516)