Except for the names of my family members, all other names have been changed.

Published in 2007 by

Academy Chicago Publishers

363 W. Erie Street

Chicago, Illinois 60610

2007 by Sandra Eugster

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without the express written permission of the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Eugster, Sandra Lee.

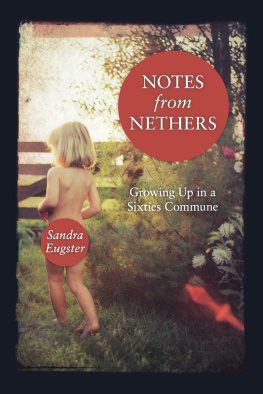

Notes from Nethers / by Sandra Lee Eugster.

p. cm.

ISBN 978-0-89733-561-4

1. Eugster, Sandra LeeChildhood and youth. 2. Communal livingVirginiaNethers. 3. Nethers (Va.)Biography. I. Title.

CT275.E75A3 2007

975.538044092-dc22

[B]

2007027782

for my mother

Contents

Introduction

My mother is always one of the last people off the airplane. Dozens of others greet their loved ones, children run happily to returning fathers, couples kiss shyly or passionately, that momentary uncertainty of reunion safely bridged, solitary travelers look around to get their bearings and then head off toward baggage. Then finally, my mother appears at the end of the corridor. She is, predictably, engrossed in a lively discussion with a fellow passenger.

My mother has been getting slighter and shorter in recent years, the hunch at the back of her neck is more pronounced. She looks small. Her cropped dark hair, well mixed with gray, is askew on her head, a product of the frequent gesture of running her hands over her head in enthusiasm or intellectual consternation. Her face is heavily lined, but its animation keeps it mobile, and directs ones attention away from her heavy cheeks and prominent nose to her bright eyes. She is utterly without cosmetics. Never once has she colored her gray strands, moisturized her skin, or plucked a facial hair. She is dressed in layers, to assist her constant taking off and putting on of jackets and sweaters in response to shifts in temperature. The loose layers are piled on heedless of how they fit together, resulting in a shaggy profile. Her perennially too-long blue jeans are rolled up at the bottom, exposing wrinkled ankle socks above tattered boys tennis shoes with their laces untied.

My mother does not tie her shoes.

No, she corrected me in a recent conversation. I do tie them, they just never stay tied. I guess no one taught me how to tie my shoes right. The result is the same, loose strings flapping around her feet, shoes half slipping off.

Thus the tying of shoes is added to the list of things my mother says she was never taught; along with how to dress well, apply makeup, or cook anything more complicated than scrambled eggs. I think skeptically of my grandmother, who was meticulously dressed in hose and heels every day well into her 90s, was famous for her beef brisket, and would never be caught with untied laces. My guess is that my mother went to some effort to avoid learning these arts.

I could be raped or murdered on a street corner, she will declare, to my ear emphasizing the raped with a kind of sexual relish, and no one would take any notice. But let me set foot outside the door with my laces untied, and the world comes to a screeching halt in its efforts to set me straight. People will dash across four lanes of traffic, hurdle walls, chase after me for blocks to let me know that my shoes are untied. I am sure she persists in this eccentricity largely because of the response it elicits.

She is carrying the usual assortment of paper bags, knapsacks, extra jackets, and whatever curious receptacle is currently posing as her purse. Unkindly, my sisters and I went through a phase of calling her a bag lady. I know that the first thing she will do, once I have greeted her, is to count her items to be sure that she hasnt lost anything. We will wait while she thinks she has lost something, and discovers that she has not.

My mother spots me, and waves wildly with both arms, burdened as they are, as if I were across a channel, not twenty feet ahead of her in a hallway.

Sandra, Sandra, come meet Marjorie, I think she might be your neighbor! she calls loudly. This used to embarrass me to no end, that my mother was so loud.

I shake hands with Marjorie, who is a pleasant but anxious-looking person, supposedly living not more than three blocks away from me.

What is the name of your neighborhood again? demands my mother. I never can remember it, but I described it to Marjorie, and she thinks she knows where it is. Its on the west side, right?

Yes, I say, reluctantly naming the area, wondering what my mother has signed me up for. Friendship? Membership in some organization? Participation in some cause?

Oh, Im so glad to meet you, says Marjorie. Your mother and I have been talking, and shes just fabulous. I wish my mother was half as active and interesting! I wish I was! And shes been telling me all about you girls, and life at Nethers! What a fantastic place that must have been to grow up in, with all that freedom, and the goats and the gardens! It sounds like paradise. Im so impressed! What was it like, really?!

How many times have I been asked that question? And felt the clash of knowing how different my answer would be from my mothers.

Oh, I say flipply, just your basic hippie commune.

Even as I say the words hippie commune, I feel guilty. We went to such pains to avoid that phrase and all its connotations. I use it now partly for shock value. How can I possibly explain? How can I convey to Marjorie in this brief moment the truth about growing up in a communal setting, about the reality of what it is like to share a bathroomor outhouseeat at the same table, sweat, cook, make music, dig holes, dance, build, weed gardens, play, and argue with seventeen or twenty other people on a daily basis? How can I get across to her that the idyllic-sounding freedom was, in reality, often terrifying and disorienting? Or reveal that as the commune grew and flourished, I became increasingly unsure and constricted? That is sort of embarrassing. Here is all this groovy open-mindedness, this free school, this culture of acceptance and tolerance, and I am so worried about everything I start getting headaches and develop this freaky nervous habit of contorting my mouth that makes me look like I have Tourettes. What the hell was wrong with me anyway? To this day, I cant think about that mouth thing without cringing, and cant be teased about it, however gently my husband does it. Truth be told, it was so hard to stop that I am still afraid, decades later, that I might again start grimacing, scowling, popping my jaw and screwing up my mouth just as I did all those years ago.

Meanwhile, my mother is standing there, immersed, as always, in her own experience, and what she thinks of as mine. She knows by now that her version of my childhood is very different from my own, but she still hopes to hear me rhapsodize about it, about the innocence, the lack of restrictions, the opportunities to exercise free will and thought. I cant muster it. The effort of explaining to Marjorie, much less to my mother, what it was really like feels insurmountable. I am reduced to platitudes.

A commune, sighs Marjorie. Thats so cool! Did everybody sleep together, and hold hands, and smoke grass all the time?

Well, it wasnt exactly like that, I answer. Anyway, I was only eight years old when it started. I can see her picturing lots of big zucchini, fine dope, and easy sex in exotic combinations and locations. She is off and running, rapt in her visions of utopian hedonism and young people with long flowing hair and headbands, communing with one another. And of course, we did all that as well, and sometimes it was wonderful. But that was only part of the story.

Next page