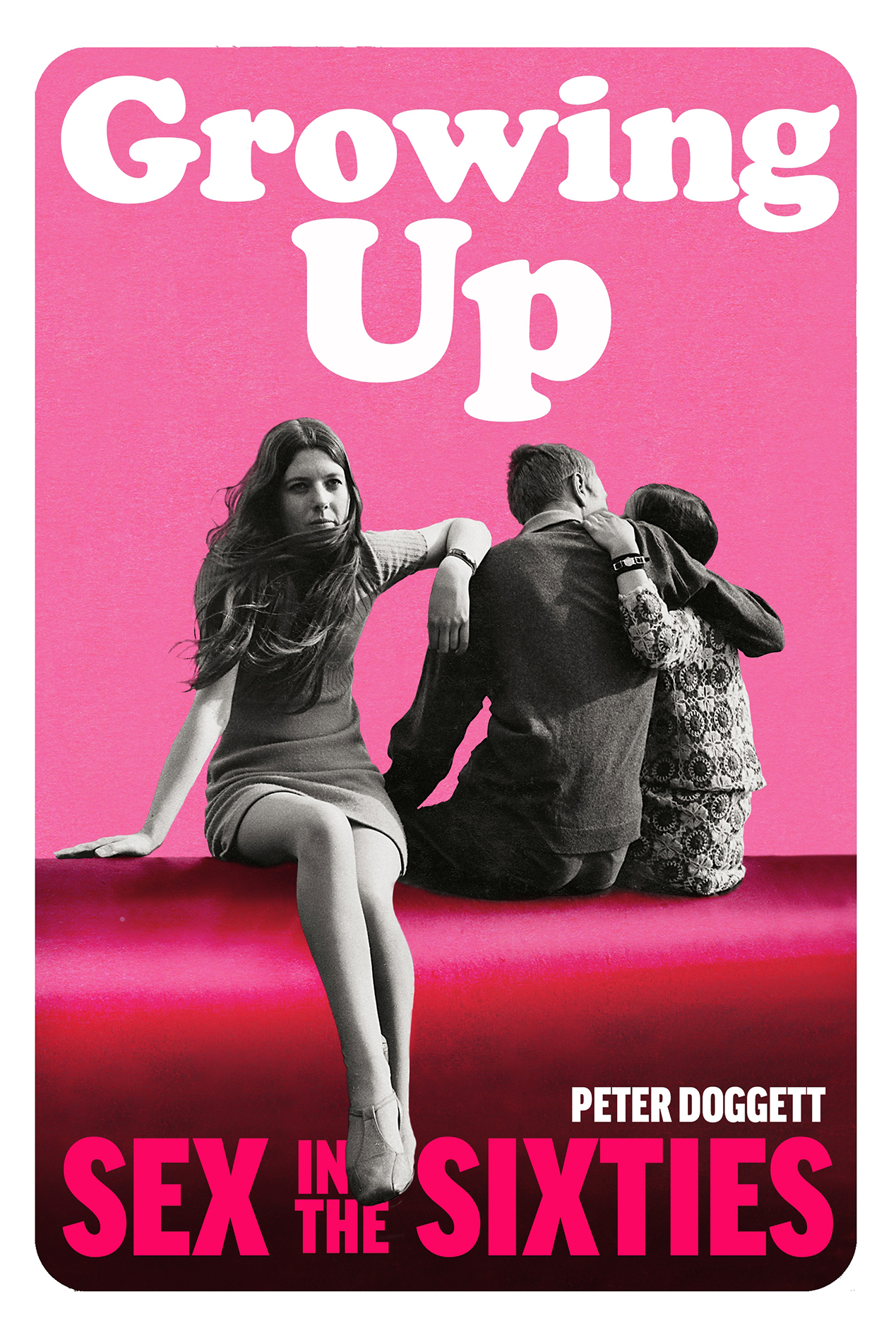

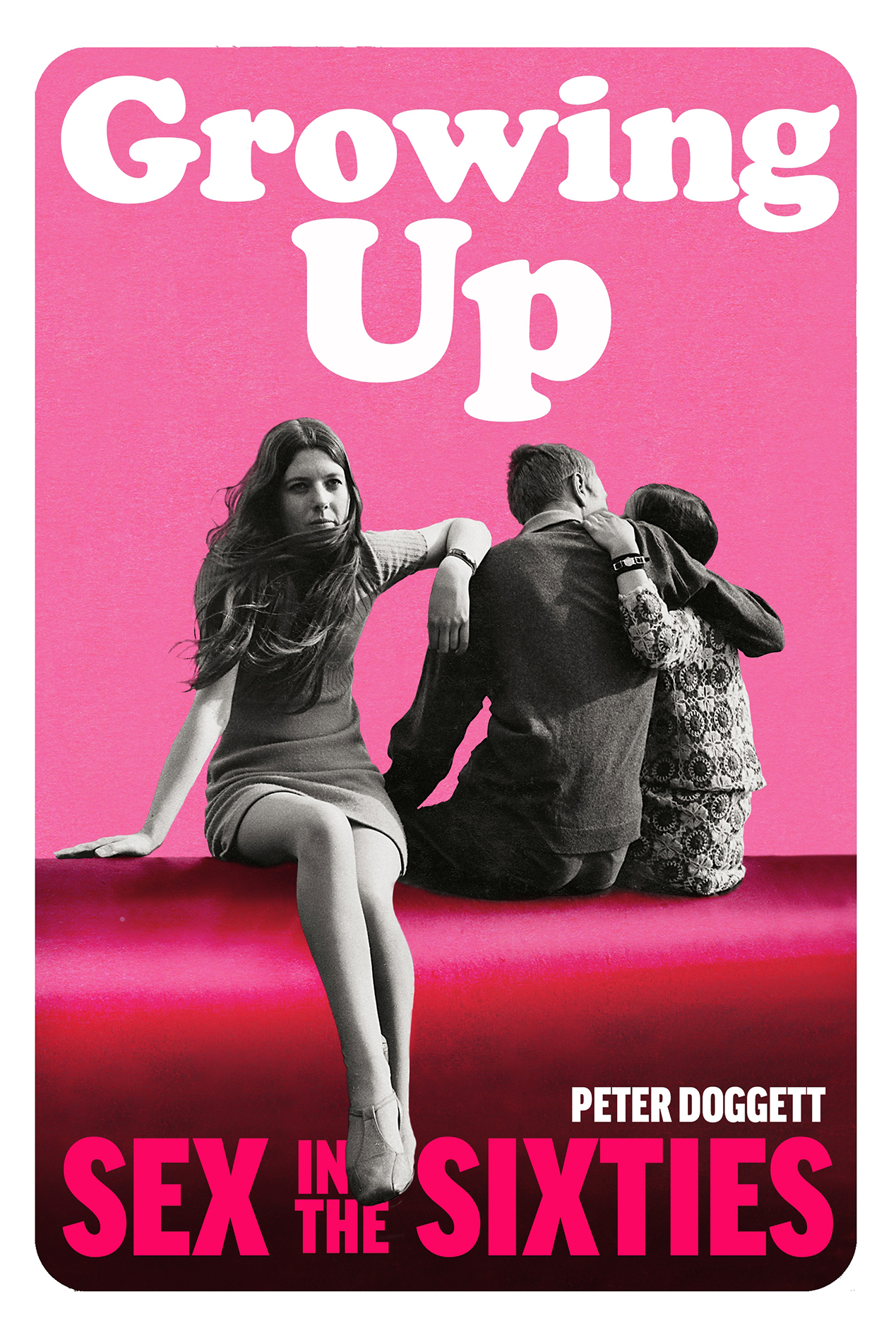

Peter Doggett

GROWING UP

Sex in the Sixties

Contents

About the Author

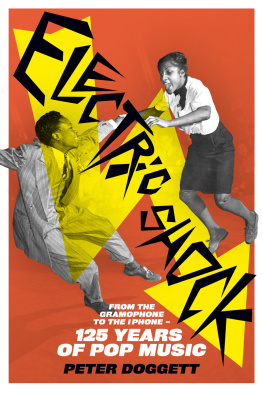

Peter Doggett has been writing about popular music and social and cultural history for more than thirty years. His books include the acclaimed Electric Shock From the Gramophone to the iPhone 125 Years of Pop Music, Theres a Riot Going On: Revolutionaries, Rock Stars and the Rise and Fall of 60s Counter-culture and The Man Who Sold the World: David Bowie and the 1970s.

Also by Peter Doggett

Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young:

The Biography

Electric Shock:

From the Gramophone to the iPhone

125 Years of Pop Music

The Man Who Sold the World:

David Bowie and the 1970s

You Never Give Me Your Money:

The Battle for the Soul of the Beatles

Theres a Riot Going on:

Revolutionaries, Rock Stars and the

Rise and Fall of 60s Counter-culture

For Rachel, Catrin and Rebecca

Introduction

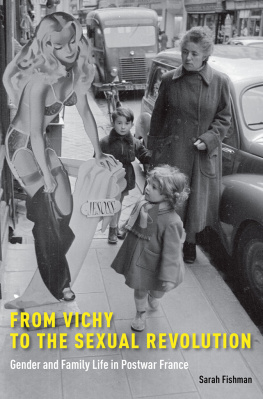

Newspapers dubbed her a naughty young foal, a colt in pasture, a fabulous little dish, the sauciest mamselle in all France. Her films were calculated pornography, flagrant, an undressing marathon. Sex and nothing but sex is rammed down ones throat, complained The Tatler as a heavily censored version of her 1956 hit Et dieu cra la femme was released in Britain. What a bore Miss Brigitte Bardot becomes, with her insistence upon being raped.

Bardot was eighteen when she married her first husband, the film director Roger Vadim, in 1952. He explained her appeal: A womans promise, a right up to that point reserved for men.

The only way in which society of the late 1950s could tolerate such flagrant desire was to rob its owner of her humanity: to reduce her to the sex kitten, so feline with her wide, Sometimes I purr. Other times I scratch. I also bite. And sometimes that violence was turned upon herself.

Brigitte Bardots first twenty-five years had been tempestuous enough. At the age of eleven, she watched her father attempt to commit suicide. By fourteen, she was on the cover of Elle magazine, and no longer her own property. She underwent an abortion when she was seventeen and another, which nearly proved fatal, before her twentieth birthday. When her parents refused her permission to marry Vadim, she attempted to gas herself; they saved her, and bowed to her wishes. Et dieu cra la femme (known in English as And Woman Was Created or And God Created Woman) established her as a worldwide scandal, who shamelessly paraded her naked flesh. She was denounced by the Pope, hounded by photographers, treated as a body rather than a woman. As the film critic Andr Bazin suggested, Vadim had effectively created a heroine who only made sense by taking off her clothes.

After she and Vadim divorced in December 1957, when Bardot was twenty-three, she tumbled through affairs with famous French actors, acted in multiple features every year, and still found time to plot her own demise. I love living far too much to ever want to stop, she insisted to reporters in February 1958, shortly after ingesting sleeping pills and once again trying to gas herself. The press was informed that she was merely suffering from the after-effects of eating too many mussels. For recuperation, she fled to Saint-Tropez, establishing the sleepy Cte dAzur resort as a honey pot for the paparazzi.

1959 brought a new affair, a second marriage, an attempt to induce an abortion by punching herself repeatedly in the stomach, another failed effort to end her life, a physical assault from her new husband (who compensated with his own effort to commit suicide) and a diagnosis that she was suffering a nervous breakdown. Her son Nicolas was born on 11 January 1960; the birth was traumatic enough to trigger a haemorrhage on a subsequent airline flight. Alarmed by her mental state, her husband distanced her from her child. In May 1960, Bardot began work on her darkest film drama to date, La Verit, in which her character employed gas to take her own life. While still ostensibly living with her second husband, she began an affair with her young co-star an entanglement so tempestuous that it led to the pair trading punches in front of reporters. That summer, her trusted secretary Alain Carr betrayed her, selling his account of her self-harm, depression and chaotic romances to the scandal sheet, France-Dimanche. His thirty pieces of silver amounted to fifty million francs (approximately 35,000 at that time).

My life is becoming impossible,

Members of the public sent letters to her hospital ward, instructing her how to kill herself more efficiently in future. Her second husband refused to visit her. The director of La Verit informed the press that She is in danger of being killed physically by her own legend. The official Vatican City newspaper placed the blame securely on the French film industry, which insisted on reifying its human fodder. But other journalists were less sympathetic.

In the Sunday Pictorial, British columnist Felicity Green wrote as if she bore Bardot an enduring animus. There was no hint of sympathy for a woman who had been objectified by the media since she was fourteen years old. Instead, Green described her dismissively as the Sex Kitten and ridiculed the triviality of her problems: They arise out of the fact that this girl, with more than her share of money, good looks and golden opportunities, seems to be determined to live her life as though it were all taking place in a film. A corny film. A bad film.

Bardot, in Greens account, was fully the author of her own misfortunes: Perhaps for the first time she will recognise the possibility that she is a victim of that lethal combination too much temperament allied to too little talent. What will she decide to do about this? Will she pull in her protruding bottom lip, grow up and be a Real Actress? With clothes on? Or will she prefer to stay a Sex Kitten with all the tiresome trimmings? In this case, I recommend her for a part in the Folies Bergre, where she could strip away to her hearts content.

Here was one authentic spirit of the decade ahead, the 1960s: the young woman, exploited mercilessly for her sexuality, and mocked when she broke under voyeuristic gaze. Like so many of those who followed her path through stardom and disillusionment, she had been immortalised and frozen in the guise of a child with the erotic magnetism of a grown woman; and paid the price. Brigitte Bardots name survived the subsequent decade as a totem of feminine allure. In 1968, she could still quicken the heart of John Lennon, who had fantasised about her since his teens, and who was so nervous about meeting her that he sabotaged the encounter by dosing himself with LSD before he arrived at her hotel. That year, her semi-naked image was marketed to teenage pop fans alongside posters of Jimi Hendrix, Jim Morrison, Mick Jagger and an anonymous nude girl on the back of a motorbike. Even when she jettisoned her career on the eve of her fortieth birthday, opting for a life of privacy and animal welfare, Bardot was stalked and wounded like a big cats prey.

Next page