Contents

Contents

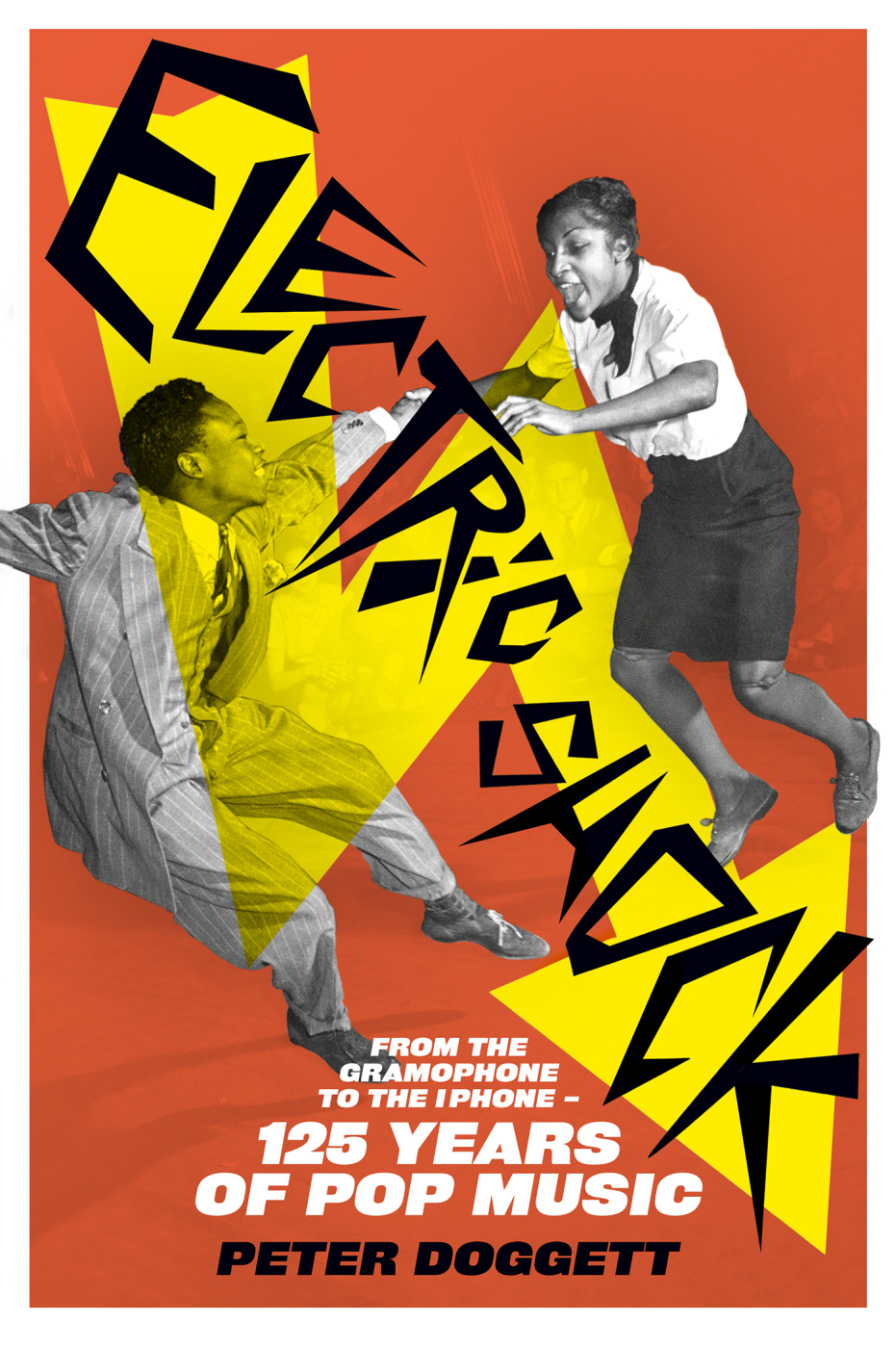

Electric Shock

From the Gramophone to the iPhone

125 Years of Pop Music

Peter Doggett

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorized distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the authors and publishers rights and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

Epub ISBN: 9781448130313

Version 1.0

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

The Bodley Head, an imprint of Vintage,

20 Vauxhall Bridge Road,

London SW1V 2SA

The Bodley Head is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com.

Copyright Peter Doggett 2015

Peter Doggett has asserted his right to be identified as the author of this Work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

First published in Great Britain by The Bodley Head in 2015

www.vintage-books.co.uk

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

For Rachel

About the Book

Popular music changed the world.

Its rhythms have influenced how we walk down the street, how we face ourselves in the mirror, and how we handle our daily conversations and encounters. It has shaped our morals and social mores; it has transformed our attitudes towards race and gender, religion and politics.

Electric Shock tells the panoramic story of popular music, from the arrival of ragtime in the 1980s to the present day. From the beginning of recording, when a musical performance could be preserved for the first time, to the digital age, when all of recorded music is only a mouse-click away; from the straight-laced ballads of the Victorian era and the coon songs that shocked America in the early twentieth century to gangsta rap, death metal and the multiple strands of modern dance music: Peter Doggett takes us on a rollercoaster ride through the history of music.

Within a narrative full of anecdotes and characters, Electric Shock mixes musical critique with wider social and cultural history and shows how revolutionary changes in technology have turned popular music into the lifeblood of the modern world.

About the Author

At the age of six, Peter Doggetts ambition was to be the drummer in the Dave Clark 5. Since then, he has been an avid consumer of popular music of all kinds. He began writing professionally in 1980, and is the author of numerous books about music and cultural history, most recently The Man Who Sold the World: David Bowie and the 1970s. His other works include You Never Give Me Your Money, chronicling the break-up of the Beatles and its personal and financial aftermath; Theres a Riot Going On, a history of the collision between rock music and revolutionary politics in the 1960s; and studies of John Lennon and Lou Reed. He also edited and contributed to Seperate Cinema, a history of African American film, and collections by several leading twentieth-century photographers. Peter lives in London, with the artist and illustrator Rachel Baylis.

www.peterdoggett.org

Also by Peter Doggett

The Man Who Sold the World:

David Bowie and the 1970s

You Never Give Me Your Money:

The Battle for the Soul of the Beatles

Theres a Riot Going On:

Revolutionaries, Rock Stars and the

Rise and Fall of 60s Counter-culture

The Art and Music of John Lennon

Are You Ready for the Country:

Elvis, Dylan, Parsons and the Roots of Country Rock

Abbey Road/Let It Be

Lou Reed: Growing Up in Public

As Rufus Lodge

F**k: An Irreverent History of the F-Word

As contributor

The 1960s Photographed by David Hurn

Art Kane

Separate Cinema: The First 100 Years of Black Poster Art

Tom Kelleys Studio

Mario Casilli

Hollywood Bound

Introduction

I

If, in 1973, you mailed a postal order for 2.50 to a box number on Merseyside, you might receive a record in an unmarked sleeve, processed-egg yellow or smoked-salmon pink. Or your money might vanish, all subsequent letters ignored.

Two times out of three, my parcel arrived; poor odds for an impecunious schoolboy, except that the prize justified the risk. It was illicit, occult, an experience unavailable from the ill-stocked record shop in my home town, where some of my schoolmates pilfered singles from the half-price box at lunchtime. Although I was too moral, or scared, to join them, I was still prepared to steal from corporations and millionaires. So I wrote to the mysterious people who made their living from selling illegal LPs bootlegs, as they were known via obliquely worded ads in the back pages of the London music papers.

That was how, at the age of 16, I first heard a recording of Bob Dylan and the future members of the Band, performing at the Royal Albert Hall in 1966. Or so it said on the yellow photocopy tucked inside the cover, the only validation of its contents.

By purchasing Royal Albert Hall, against the wishes of the artist and his record company, I was buying my way into a secret society: insider trading, if you like, in the mythology of rock n roll. I was already aware that this recording was regarded by many as the artistic pinnacle of Dylans career, and its aesthetic worth was multiplied for me by its exclusivity. What I hadnt anticipated was its sonic force, delivered with the fury and contempt of a man who sounded as if he were staring an apocalypse in the eye.

The albums climax has become a piece of 1960s folklore. It documents a confrontation between audience members who had convinced themselves, against all aural evidence, that Dylan was only valid with an acoustic guitar; and a man who had staked his sanity on living with extremes, among them the crushing volume of an electric band. Judas, someone called from the stalls. Dylan drawled a contemptuous response, before leading his musicians into Like a Rolling Stone.

Adjectives wouldnt begin to convey the effect of immersing myself in that moment, and that music, over the months ahead. As I slid towards a teenage nervous breakdown, it offered me not salvation, exactly, because my fate was sealed; not transcendence, because when it was over I still had to face my own existence; but recognition, the hint that I might not be entering the darkness alone; that one could go down into the pit defiantly, self-righteously; that someone else had been there before. Later, after the apocalypse, bemused to have survived, I gathered from that same performance the hope of renewal, just as Dylan had weathered the storm (in another mythological tale) to find respite in a Woodstock basement.