This is a work of nonfiction. Nonetheless, some of the names of the individuals involved have been changed in order to disguise their identities. Any resulting resemblance to persons, living or dead, is entirely coincidental and unintentional.

Copyright 2018 by Anya Yurchyshyn

All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Crown, an imprint of the Crown Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York.

crownpublishing.com

CROWN is a registered trademark and the Crown colophon is a trademark of Penguin Random House LLC.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available upon request.

ISBN9780553447040

Ebook ISBN9780553447057

Cover design: Elena Giavaldi

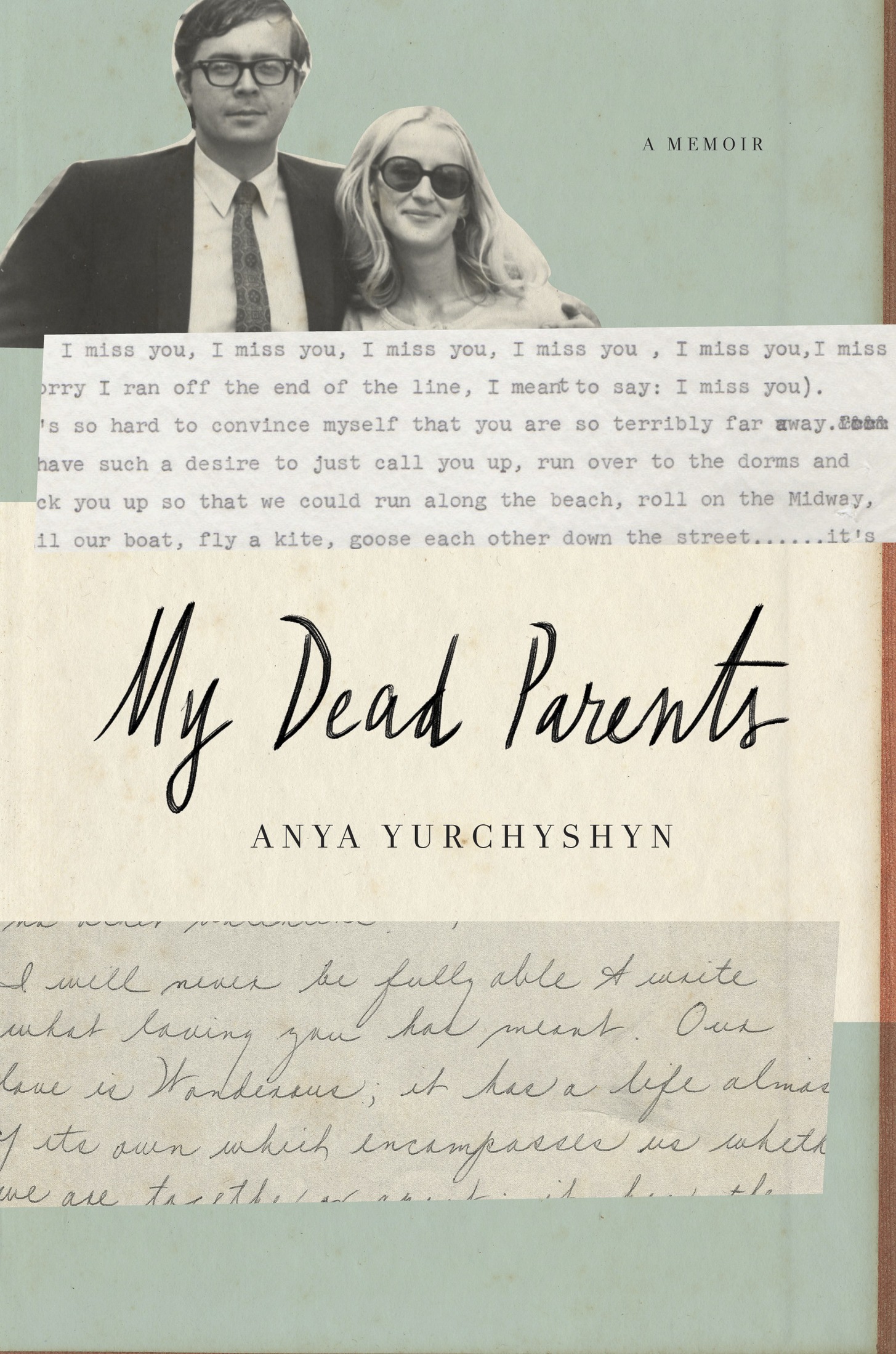

Cover photographs: (parents) courtesy of the author; (typed letters) George Yurchyshyn/courtesy of the author; (handwritten letter) Anita Yurchyshyn/courtesy of the author

v5.2

ep

Contents

Whereas the beautiful is limited, the sublime is limitless, so that the mind in the presence of the sublime, attempting to imagine what it cannot, has pain in the failure but pleasure in contemplating the immensity of the attempt.

IMMANUEL KANT

!

(Onto the horse!)

M y mother, Anita, died in her sleep in 2010, when she was sixty-four and I was thirty-two. The official cause of death was heart failure, but what she really died from was unabashed alcoholism, the kind where you drink whatever you can get your hands on, use your bed as a toilet when you cant make it to the bathroom, and cause so much brain damage you lose the ability to walk unsupported. The cause of her death was herself, and her many problems.

The month after she died, I began cleaning out her house, my childhood home, in downtown Boston. As a kid, my house sometimes seemed enchanting, filled to the ceiling with items my parents had collected on their many trips around the globe. But when my father, George, was killed in a car accident in Ukraine in 1994, my mother lost interest in our home, and it started to die as well. By the time she passed away, treasured rugs were being eaten by moths and mice, the fire escape was dangling off the back, and some windows wouldnt open, while others wouldnt close. Everything that once seemed special was chipped or cracked and buried under sticky dust. I saw cleaning out the house as my last goodbye to her and my dad, and I was eager to finally be rid of them. I thought I would box up what I wanted, toss what I didnt, and avoid being caught by what had become its most potent forcesadness.

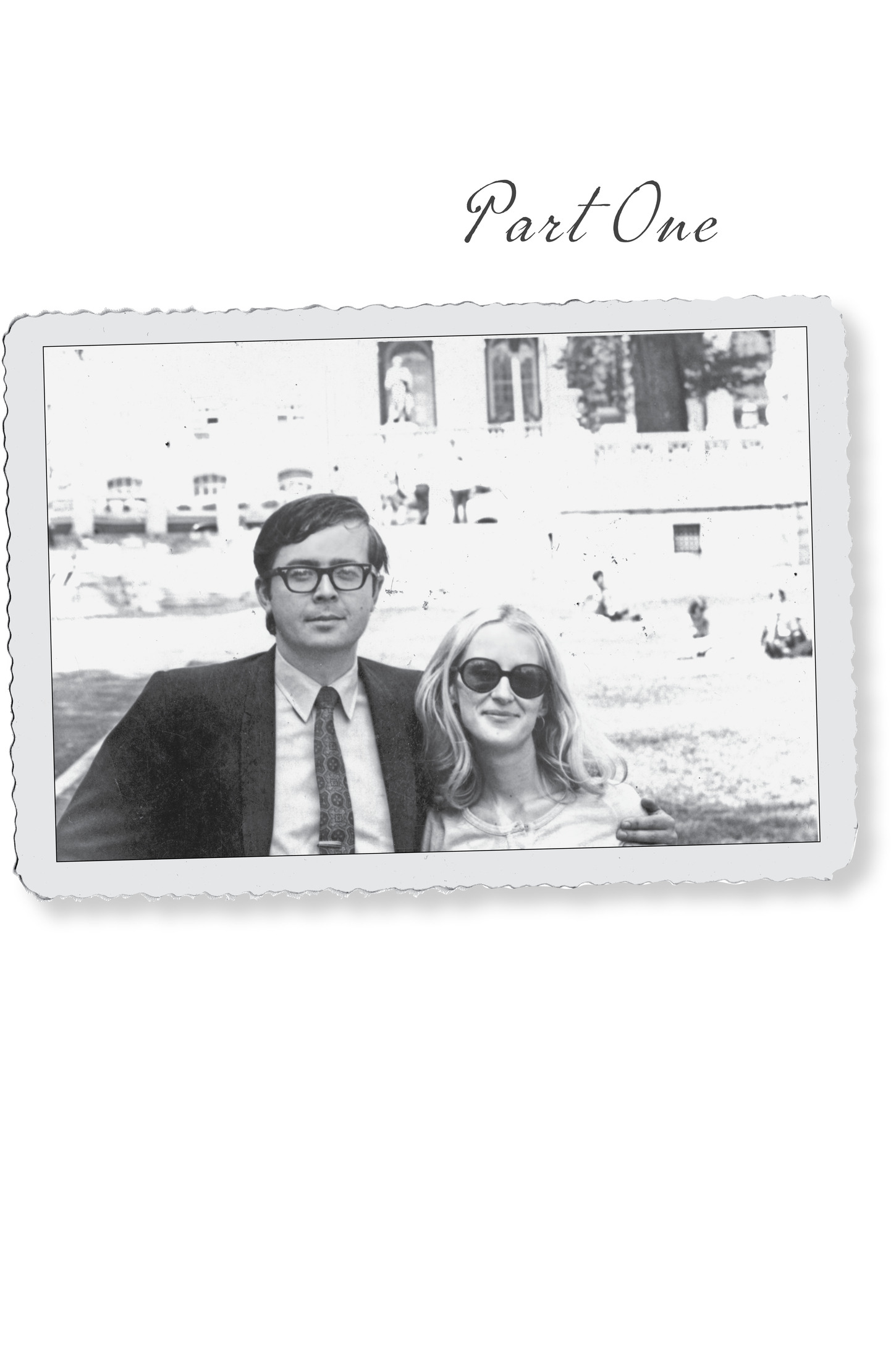

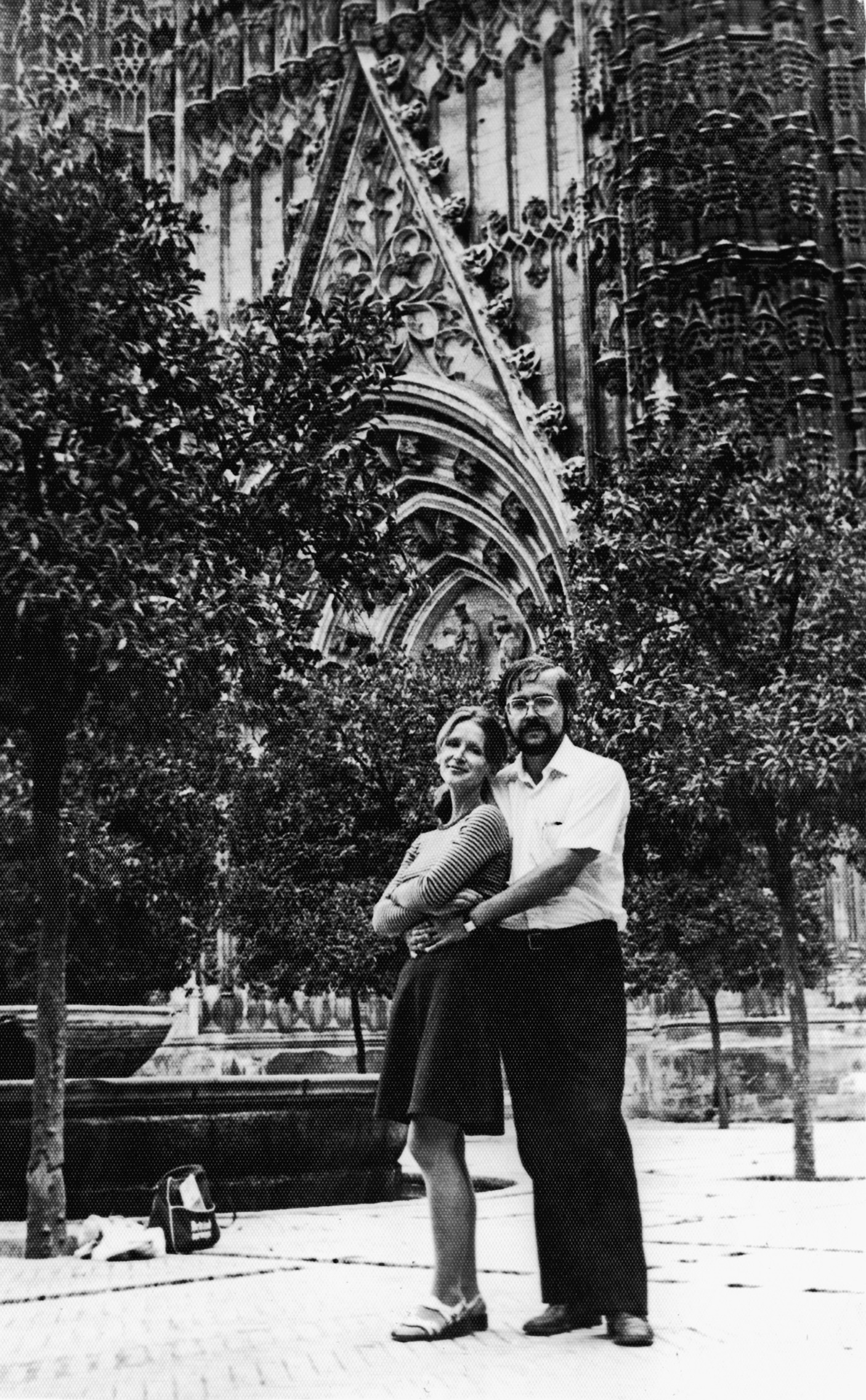

My parents were intellectuals with exciting careers, but that wasnt what mattered to me as their child. My father had been emotionally distant and occasionally abusive. My mother hadnt protected me. She was resentful and selfish, and this was before her drinking brought out, or created, qualities that were much worse. My parents were married for twenty-seven years, but rarely seemed to even like each other. I believed that theyd never been in love.

I began my work in my mothers large study. Growing up, it had been the part of the house that was specifically hers, an area where the air was still and sacred. It was where she wrote and practiced her speeches for the Sierra Club, kept her favorite books and special jewelry. But during the last ten years, it became a haphazard storage room for everything from stained sheets to months of unopened mail. I spent days sorting the clothing piled on the rooms red couches and the incredible amount of panty hose shed purchased from Filenes Basement and never worn. Id anticipated this task for years, and getting rid of things so banal and expected was both boring and surreal: There goes that stained cotton turtleneck, that long pink coat she made my father buy her because she thought it made her look regal.

I split the wall of books between boxes that would be donated and boxes that Id bring back to Brooklyn. I reached deep into her closet and, when I came across something that my sister and I might want to keepsilk kimonos, a leopard jacketI brought it into my mothers room and placed it on her bed, which had been stripped by her aide the morning shed been found dead in it.

I tried to summon a memory of getting rid of my fathers belongings after he died, but couldnt. Then I remembered that my mothers best friend, Sylvia, had traveled from Chicago to help with the job, sparing me from having to fold his suits and throw away his underwear, and from seeing my mother doing it. Although the house had been my parents and theyd acquired the majority of its contents together, Id gotten used to thinking of it as my mothers. What I was going through those first few days was the soggy life shed lived after my father died.

Once Id pried loose this first layer, I began to move more slowly. I had to pay attention to what was passing through my fingersmy mothers work files, broken necklaces with beads my sister might want to repurpose, our grade-school report cards. At the bottom of a small wooden chest, I found a collection of letters bound by a cracked rubber band. After Id managed to remove it, I unfolded the letter on top of the pile. It was typed on thin, crinkly paper, dated 1966, and addressed to my mom, who would have been twenty-one.

I miss you, I miss you, I miss you, I miss you, I miss you, I miss you, I (sorry I ran off the end of the line, I meant to say: I miss you). Its so hard to convince myself that you are so terribly far away. I have such a desire to just call you up, run over to the dorms and pick you up so that we could run along the beach, roll on the Midway, sail our boat, fly a kite, goose each other down the street

I laughed. Whod write such goofy things to her? I scanned the pages that followed, but it was only the signature, handwritten in blue ink, that revealed the authors identity: George. What? I whispered. My father would have never written such silly things or have been so free with his affection.

I made my way through the rest. In 1971, my father wrote, Whenever I leave you I feel a powerful and wonderfully terrible series of emotionsthere is an emptiness inside me, a true aching of the heart. It is a longing and a dull sorrow for leaving behind that which I love.

In 1973, my mother told him that shed never be fully able to write what loving you has meant. Our love is wondrous; it has a life almost of its own which encompasses us whether we are together or apart. Her tight, Catholic school script was barely legible, but the ink was steady and bold. Shed transcribed her devotion in a fever. When I flipped the page over and ran my fingers across it, I felt the force of the words shed pressed into it.

What I was reading contradicted what Id long ago decided: that my parents had never been happy with each other, never had hope. I couldnt believe that my father could have been so articulate and vulnerable, or that my mother had ever adored him so intensely. My brain was in revolt. What I was reading seemed to have been written by strangers, not the people Id known. I read their letters again and again, arguing with what I found. But as I continued to find proof of their love, I realized that I was defending the story Id arrived with against mounting counter-evidence, and losing.