Contents

Guide

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

For Merle and Mei, with love

First picture section

( Charlotte Zeepvat/ILN/Mary Evans Picture Library).

( Charlotte Zeepvat/ILN/Mary Evans Picture Library).

(both pictures National Portrait Gallery, London).

(image courtesy of the author).

(all courtesy of Nick Locock and Philippa Duckworth).

(all courtesy of Nick Locock and Philippa Duckworth).

( National Portrait Gallery, London).

Second picture section

( Library and Archives Canada).

( National Portrait Gallery, London).

( National Portrait Gallery, London).

( William James Topley/Library and Archives Canada/PA-013031).

(image courtesy of the author).

( Mary Evans Picture Library/National Magazine Company).

( Argyll Museum).

( Christies Images).

Very special thanks go to Nick and Sara Locock, Vicky Trelinska and Marek Trelinski, Basil Collett, Philippa Duckworth and Michael Gledhill QC for their enthusiasm, advice and selfless sharing of their own time and information. This book could not have been written without them.

Many thanks to Carolyn and Roger Taylor for generous accommodation, advice, gorgeous food and great fun in Ottawa. For the Bermuda section, I am indebted to Lord Waddington (what a serendipitous meeting), John Adams and Andrew Trimingham.

This book could not have been published without the lovely people at Chatto: Juliet Brooke, Clara Farmer, Penny Hoare, and my agents Christopher Sinclair-Stevenson and Broo Doherty.

In addition, I would like to thank (in alphabetical order) for guidance, advice and help, John Aplin, Simon Butcher, Caroline Dakers, Henrietta Garnett, Jake Gorst and Tracey Rennie Gorst (for Corsi information), Henrietta Heald, Sarah James, Anne Jordan, Dominique Kenway, Joanna Marschner at HRP, Genevieve Muinzer at HRP, Laura Payne, Vanessa Remington at the Royal Collection, Jane Ridley, Nicholas Robinson at the Fitzwilliam Archives, Sue Snell, Vanessa Story and Hugo Vickers.

Many thanks to the RSL Jerwood Award committee for their grant which helped with the costs of researching this book. Grateful thanks also to the hardworking staff at the Alberta Government archives, the British Library, the British Newspaper Archives, the Canadian Archives, Ottawa, the Imperial War Museum archives, Liverpool Central Library, the London Library, the London Metropolitan archives, Malta Tourism Authority, the National Archives, Kew, National Art Library, National Gallery archives, National Library of Malta, National Portrait Gallery archives, Rideau Hall, Ottawa, Swan Hotel in Lavenham (John Morrell, Ingo Wiangke and Kate Bourdillon), Tate Britain, University of Glasgow/Whistler archives and The Womens Library.

Many thanks as well must go to all those authors before me who have written about Queen Victorias family, including those who have been given access to the royal archives in the past and have published excerpts of letters and journals in their books and articles.

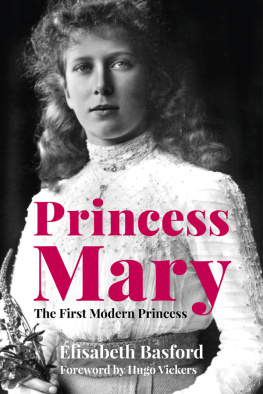

The name of Sir William Blake Richmond is little remembered today, but in the late nineteenth century he was connected to almost everyone in the fashionable art world. As a painter who numbered amongst his friends William Morris, Robert Louis Stevenson and William Holman Hunt, Richmond moved with ease in the varied worlds that made up London Society. One day, as he was busy painting in his studio, he was annoyed to be disturbed by a servant announcing an unexpected visitor. Richmond yelled angrily, Tell her to bugger off, unaware his visitor was close enough to hear. Not till Ive seen you was the mild and amused response from Princess Louise.

* * *

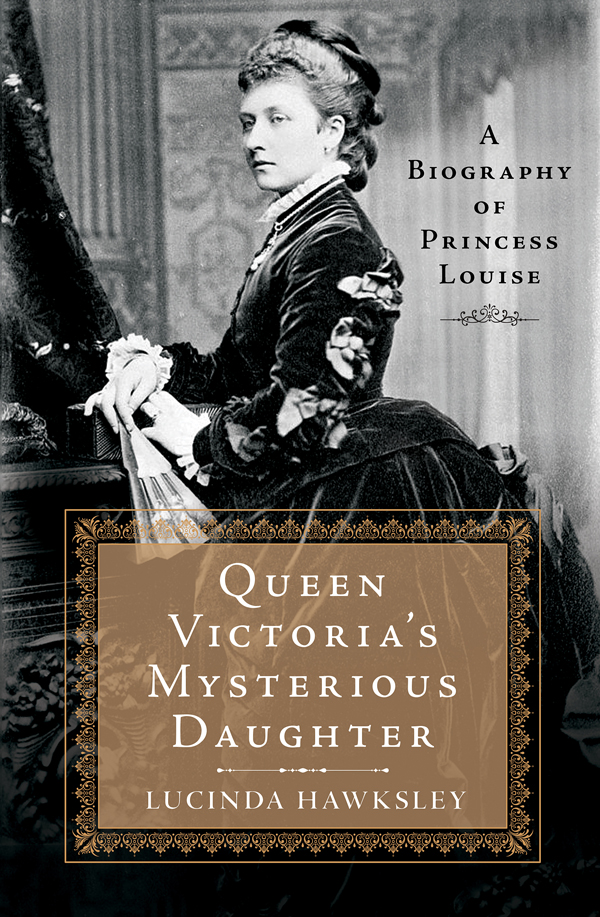

I first discovered Princess Louise when researching my biographies of the Pre-Raphaelite model Lizzie Siddal and the artist Kate Perugini. This mysterious princess kept appearing in unlikely circumstances: visiting Dante Rossetti when he was ill (and deemed mad); remaining friends with the difficult James Abbott McNeill Whistler, despite his financial and social embarrassments; arriving to see John Everett Millais on his deathbed, or taking tea with Arthur Sullivan, who called her my Princess Louise in a letter to his mother. I wondered who this art-loving, aesthetically minded princess was. The more vague appearances she made in my research notes, the more I wanted to find out about her. When I discovered she was not only a friend to artists, but a sculptor in an age when few women broke into such a masculine field, I determined to discover more about her life.

* * *

Princess Louise was born in 1848 and lived until 1939; her life encompassed almost a century of extraordinary and often terrifying achievements, conflicts and societal change. At the time of Louises birth, British women and girls were, legally, the property of either their father or their husband. (Queen Victoria might have been the most powerful woman in the world but she was fervently against the majority other women who fought to be given the most basic human rights.) By the time of Louises death, British women had gained the vote and were striving to achieve a world in which men and women could truly be equal. Louise had played an important part in the educating of these powerful new women. She was, as the daughter of a monarch, famous and celebrated in her lifetime, but, like so many women of her era, she has been all but forgotten since.

When I started my research, I mentioned it to a couple of fellow authors who advised me against it. Both of them had attempted to look into Princess Louises life themselves. One warned me, you will come up against a brick wall at every turn. That intrigued me. They were quite right, of course.

After discovering the bare bones of Louises life and beginning to read existing books about her, I applied to the Royal Archives. Many months later I received a response telling me I was welcome to visit the archives and detailing what times they were open and what I would need to bring with me. It all seemed very positive, until I reached the bottom of the letter. Almost as an afterthought was the comment We regret that Princess Louises files are closed. I could visit the archive buildings, but would not be allowed to view the files I needed to see.

I tried her husbands familys collection in Inveraray, Scotland, where my several applications (phone and email) were kindly but firmly rebuffed. On my initial approach I discovered that their archives were in the process of being rehoused and it would be over a year before they could be accessed again. More than a year later, I was told they were still inaccessible; and the same some months afterwards. My last two enquiries simply went unanswered. When I visited Inveraray as a tourist, in the summer of 2012, I was told by a curator inside the castle that the archives had not been rehoused. The curator also mentioned that it was almost impossible for researchers to get into the archives; even people working at the castle itself were denied access.

I discovered that it was not only information about Princess Louise that had been hidden away, but information about a vast number of people who had played a role in her life, including royal servants and her art tutors. A great many items about these people that one would expect to be in other collections have been absorbed into the Royal Collection. Archivists at the National Gallery, Royal Academy and the V&A, as well as overseas collections in Malta, Bermuda and Canada, were bemused to discover that primary sources I requested had been removed to Windsor. Over the decades, there has been some very careful sanitising of Princess Louises reputation and a whitewashing of her life, her achievements and her personality.