Barakaldo Books 2022, all rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted by any means, electrical, mechanical or otherwise without the written permission of the copyright holder.

Publishers Note

Although in most cases we have retained the Authors original spelling and grammar to authentically reproduce the work of the Author and the original intent of such material, some additional notes and clarifications have been added for the modern readers benefit.

We have also made every effort to include all maps and illustrations of the original edition the limitations of formatting do not allow of including larger maps, we will upload as many of these maps as possible.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

TABLE OF CONTENTS

ILLUSTRATIONS

SPECIAL INTRODUCTION

AUTHORS INTRODUCTION

CHAPTER I.

NOTE.

CHAPTER II.

CHAPTER III.

CHAPTER IV.

NOTE.

CHAPTER V.

CHAPTER VI.

CHAPTER VII.

CHAPTER VIII.

NOTE.

CHAPTER IX.

CHAPTER X.

CHAPTER XI.

NOTE.

CHAPTER XII.

CHAPTER XIII.

NOTE.

CHAPTER XIV.

CHAPTER XV.

CHAPTER XVI.

CHAPTER XVII.

CHAPTER XVIII.

POSTSCRIPT.

CHAPTER XIX.

CHAPTER XX.

CHAPTER XXI.

CHAPTER XXII.

CHAPTER XXIII.

CHAPTER XXIV.

CHAPTER XXV.

CHAPTER XXVI.

CHAPTER XXVII.

CHAPTER XXVIII.

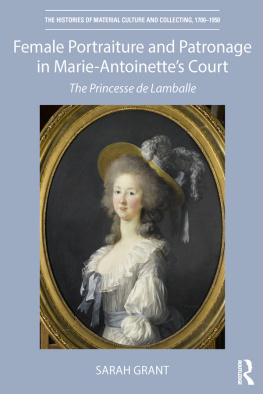

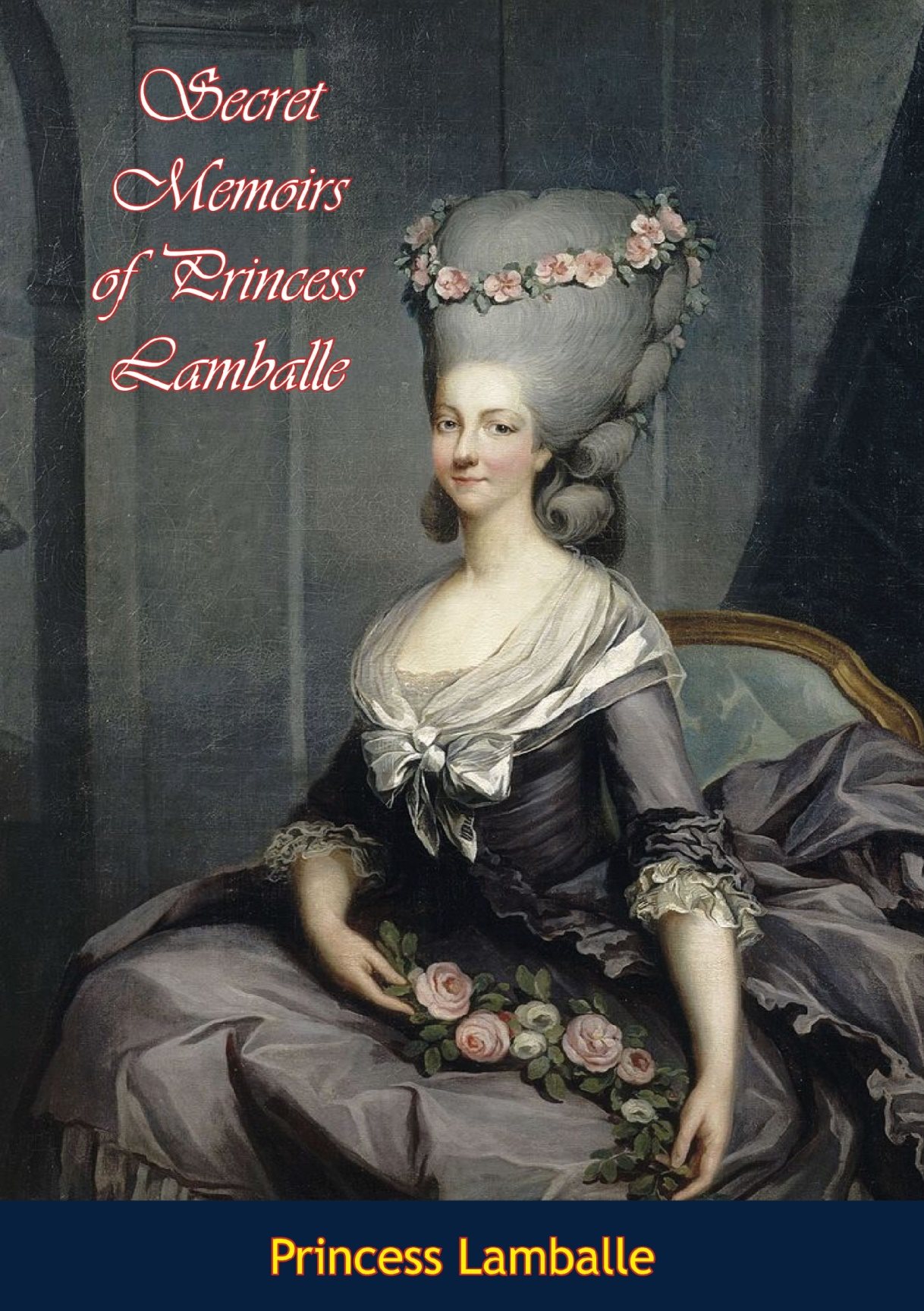

SECRET MEMORIES OF PRINCESS LAMBALLE

BEING

HER JOURNALS, LETTERS, AND CONVERSATIONS DURING HER CONFIDENTIAL RELATIONS WITH

MARIE ANTOINETTE

WITH ORIGINAL AND AUTHENTIC ANECDOTES OF THE ROYAL FAMILY AND OTHER DISTINGUISHED PERSONAGES DURING THE REVOLUTION

EDITED AND ANNOTATED BY

CATHERINE HYDE

MARQUISE DE GOUVION BROGLIE SCOLARI

IN THE CONFIDENTIAL SERVICE OF THE UNFORTUNATE PRINCES

WITH A SPECIAL INTRODUCTION BY

OLIVER H. G. LEIGH

AUTHOR OF

FRENCH LITERATURE OF THE XIXTH CENTURY, etc.

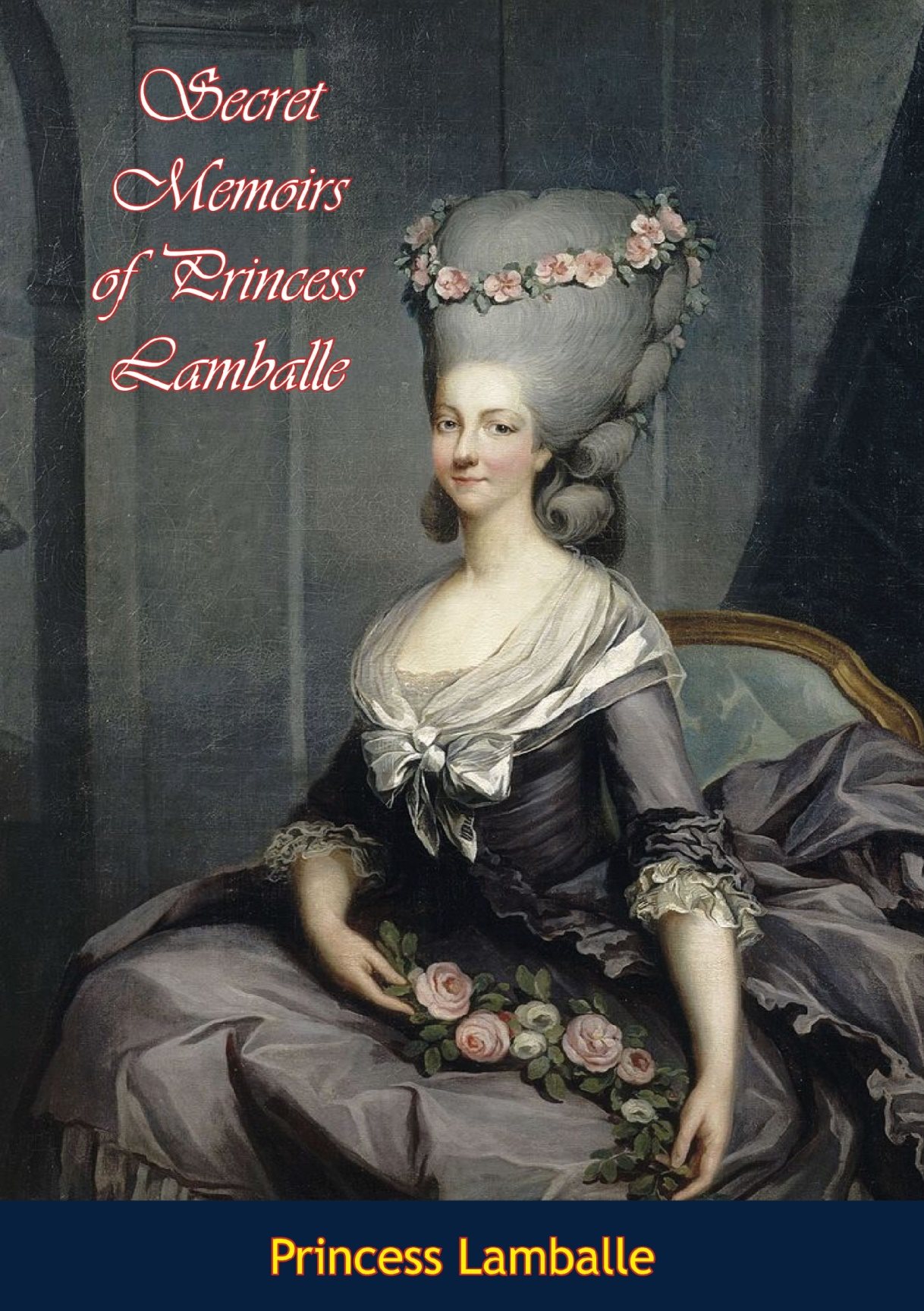

THE LAST ADIEU OF LOUIS XVI. AND MARIE ANTOINETTE

Photogravure after a painting by Meisel.

ILLUSTRATIONS

THE LAST ADIEU OF LOUIS XVI. AND MARIE ANTOINETTE

Photogravure after a painting by Meisel.

LAST DAYS OF LOUIS XVI AND FAMILY

Photogravure after a painting by Benesur.

SPECIAL INTRODUCTION

MARIE THRSE LOUISE DE SAVOIE-CARIGNAN, Princess de Lamballe, was fated to be not only an eyewitness but a victim of the Reign of Terror. She was born in Turin in 1749, was married in 1767 to Stanislaus, Prince of Lamballe and son of the Duke of Penthivre, which brought her into the relationship of sister-in-law to the Duke of Orlans. Her husband died within a year, leaving her, as she expresses it, a bride when an infant, a widow before I was a mother or had a prospect of becoming one. A marriage was proposed between the Princess and Louis XV., but it fell through. In her retirement she gained the friendship of Marie Antoinette, who appointed her superintendent of the royal household on the accession of Louis XVI. This official connection grew into a sisterly intimacy of the most cordial kind. Their youth of brilliant promise was soon overshadowed with ominous troubles. The lighter temperament of the Queen was happily balanced by the philosophic gravity of the Princess, who foresaw the bitter fruits of the conditions in which her royal mistress had been reared and would not radically change. This journal-record of experiences and reflections is as pathetic a tale as has ever been told. Lit up as it is with gleams of the merriment supposed to be the normal atmosphere of court life, it progresses with the doleful tread of a funeral march, each step lessening the too short space that separates the palace from the dungeon, the glamor of hollow sovereignty from the bloody tyranny of an irresponsible populace.

The Princess Lamballe, as will be seen, was as loyal to her own conscience as to her less clear-sighted mistress. When the catastrophe was impending the Queen and King implored her to leave France and so save her life. The beauty and purity of her character was equalled by her devotion to duty and her courage. She scorned to leave her friends in the hour of peril, faithful among the faithless titular nobility who scampered away to safe hiding-places until they might creep back in the returning sunshine. She was harassed with repeated attempts at bodily injury, and when arrested, calmly refused to forswear her principle of fealty to the monarchy, while cheerfully willing to accept the mandate of the nation. Thereupon the gentle and brave woman was stabbed to death by the fiends who invaded her cell, and who added an exquisite pang to the sufferings of the Queen by parading the head of the Princess, on the point of a pike, before the window where her mistress was expected to see it.

How the Princesss journal came to light is narrated in the following pages. It is edited and annotated, in a liberal sense of those terms, by the lady who, in her youth, was the confidential secretary and messenger, in fact a diplomatic maid-of-all-work, of the Princess. From the copious diary of the latter, supplemented by the graphic and elaborate additions and comments of the brilliantly gifted editor, to whose care the diary was in-trusted, we get a most impressive realization of the life endured by Louis XVI. and Marie Antoinette in those appalling years of doom.

The portraiture of these unconsciously fatalistic royalties is eloquently painted in many offhand touches, the force of which has been made clearer by lapse of years. The young Queen owed more grudges than gratitude to her imperial mother for her bringing-up. Conspicuous lack of common sense may more justly be blamed for the failure of her life than any of the faults charged against her. The Princess avers that Marie Antoinette was an unsophisticated country girl at heart, with a natural dislike for fine dress and jewel display. The artifice and pomposity of the court were alien to her artless nature. She loved genuine jollity, unhampered by stilted conventionalities, and preferred the society of pleasure-loving youth to that of the elderly aunts of the King, who sought to rule her as they dominated him. Add to this wholesome rebelliousness an unfortunate hereditary and exaggerated superstition as to the divinity of royalty, and we have the elements of the hopeless deadlock which culminated in the Revolution.

Marie Antoinette is here shown as developing an unexpected solidity of character as the need for it became more insistent. In the beginning she made light of national susceptibilities, a fatal folly in ordinary circumstances, much more serious in those times. As the Kings weakness and her own unpopularity increased, she rose to the situation with somewhat of her mothers masterful spirit, unwise, but compelling a qualified admiration. When the Princess Lamballe was the transmitter of outside opinion and counsel to the King through the Queen she backed it up by candid advice of her own, with the usual result of offending, without influencing, the object of her solicitude. For a time this intercourse, or at least this faithful remonstrance, ceased, to be resumed when its wisdom had struck home. But it was then too late to undo past follies, and a few lingering stupidities were never given up. The old nobility felt their order had been humiliated by the persistently alien Queen. The common people were incensed against a monarchy that reveled, as they were assured, in wanton luxury while famine threatened the land. The resurrected States General were regarded as an audacious attempt to set up the vulgar human against the Lords anointed. Marie Antoinette made no politic effort to veil her sovereign contempt for the masses when massed. As individuals no one was at heart more of a friend of the people. She proudly disdained to exchange thoughts with our Franklin or the sages of France on the social convulsions raging around. I was the only silent individual among millions of infatuated enthusiasts at La Fayettes return to Paris, at the head of the throng he so half-heartedly led. There is a queenly grandeur in this attitude despite its perversity. Of all infatuated enthusiasts she herself was at that supreme moment the queen, and did not know it. Weakness was behind that show of strength, for she was even then dallying with Mirabeau, the man of the people, the man of the hour; friend of republicans, friend of the monarchy. Disguised in monkish robe and cowl he crept into the palace and negotiated for terms as between the dissolving view of the throne and the coming people, and his impecunious but statesmanlike and doubtless honest self. When he was cut off in the critical phase of the struggle, (by disease, or, as here suggested, by poison), the cord was snapped that held up the curtain on the last act but one of the tragedy of a make-believe reign. Then it fell, and in the black gloom of the background was played out the final tableau of horrors on which this book throws so painful a light.

Next page