Empty Chairs

Selected Poems

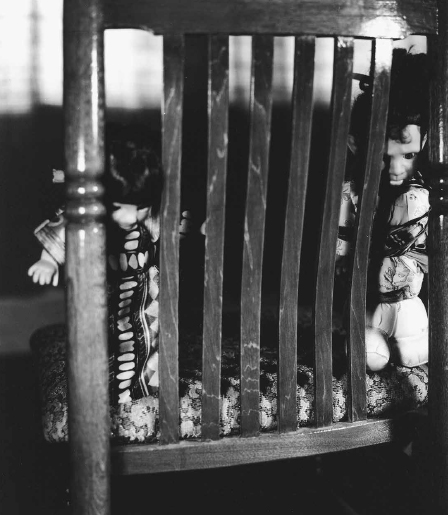

Liu Xia Translated from the Chinese by Ming Di and Jennifer Stern Foreword by Herta Mller and Introduction by Liao Yiwu Graywolf Press Poems and photographs copyright 2015 by Liu Xia English Translation and Translators Afterword copyright 2015 by Ming Di and Jennifer Stern Foreword copyright 2015 by Herta Mller, English translation copyright 2015 by Philip Boehm Introduction copyright 2015 by Liao Yiwu, English translation copyright 2015 by Ming Di and Jennifer Stern Some of these translations first appeared through the following organizations and in the following publications: PEN America, Chinese PEN, the BBC, the Guardian , the Margins (journal of the Asian American Writers Workshop), Poetry, Poetry East West , the Poetry Society of America, and Words without Borders. Liu Xias photographs on the cover and interior were provided generously by Guy Sorman. Liu Xia entrusted Guy Sorman with her original prints, which he smuggled out of China and has shown in galleries around the world.

This publication is made possible, in part, by the voters of Minnesota through a Minnesota State Arts Board Operating Support grant, thanks to a legislative appropriation from the arts and cultural heritage fund, and through grants from the National Endowment for the Arts and the Wells Fargo Foundation Minnesota. Significant support has also been provided by Target, the McKnight Foundation, Amazon.com, and other generous contributions from foundations, corporations, and individuals. To these organizations and individuals we offer our heartfelt thanks.

A Lannan Translation Selection Funding the translation and publication of exceptional literary works Published by Graywolf Press 250 Third Avenue North, Suite 600 Minneapolis, Minnesota 55401 All rights reserved. www.graywolfpress.org Published in the United States of America ISBN 978-1-55597-725-2 Ebook ISBN 978-1-55597-914-0 2 4 6 8 9 7 5 3 1 First Graywolf Printing, 2015 Library of Congress Control Number: 2015939979 Cover design: Jeenee Lee Design Cover art: Liu Xia

Foreword: A Mix of Silk and Iron

Liu Xias poems are inevitably lyrical and inescapably documentary. They take her real life and put it on poetic record.

Their sentences oppress, their images are both matter-of-fact and full of despair: When the show is over, I stay on stage with myself: one of me is tearful the other laughing loudly. Or: Ive been looted. Or: My mind is filled with straw. Or: You love your wife and are proud she stays with you. Of course, we realize this woman is the wife of Liu Xiaobo, the Nobel laureate from China and that countrys most famous political prisoner, now in his fifth year of his eleven-year sentence. His crime: the Charter 08 manifesto, which far from making aggressive demands offered measured, even cautious suggestions for converting Chinas communist, one-party system into a free and humane society.

For that, he was given eleven years of prison, and his wife is subjected to constant surveillance, house arrest, isolation. Day in and day out she is unable to take a single step that goes unwatched. And this is the merciless substance of these poems, their point of departure. Meanwhile, the regime is not content to torment Liu Xia alone for her husbands outspokenness, but has extended its retribution to other family members. To unsettle her further, they have arrested Liu Xias brother on a ridiculously trumped-up charge. Despotism plain and simple.

In her poem Snow, the author evokes her brothers birthday. I freeze on the inside when I read the sentence: it must be hard to be my brother. Out of this pain come the pangs of conscience, the creeping guilt, simply because nothing can be done about the groundless punishment this big state is inflicting on this small brother, this little brother who was born on the Day of Great Snow. Simple contrasts on a steep poetic slope. Clear in their helplessness, lapidary but still tender. A quiet imploring is also a loud clamor.

Liu Xias poems are a mix of silk and iron. Because while iron political despotism rules outside, intimacy with all its hardships reigns within, the enigma of strong emotion. Over and over we read about time, the ladder of time. Or: Death from twenty years ago returns / it comes and goes like time. Here in these poems, time is exactly what it is in the everyday life of the author: stolen by the state. No matter how many details we examine, the longer we look at the particulars, we cannot escape the horrifying insight: the full length of stolen time is nothing less than stolen life.

Liu Xias poetry is about self-assertion in a stolen life. Her poems possess a dignity that always manages to arise anew whenever it is battered down. HERTA MLLER Translated from the German by Philip Boehm

Introduction: The Story of a Bird

Liu Xiathe first poem of hers that filled me with wonder was One Bird Then Another, written in May 1983. Recently, I was filled with grief, when I read her poem about a tree, How It Stands, written in December 2013. Between the two poems, thirty years had passed. What had happened in between? When we first met, we were very young, and knew nothing but writing poetry.

The bird called Liu Xia lived in a large cage-like room on the twenty-second floor of a building on West Double Elm Tree Lane in Beijing. I traveled from Sichuan to meet her and climbed up the stairs as the elevator was broken. From the moment I knocked on the cage door, Liu Xia never stopped giggling. Her chin became pointy when she smiled, and she laughed like a bird, unrestrained. No wonder she wrote this Then, we started to hate winter, the long slumber. We put a red lamp outside overnight so its light would tell our bird we were waiting.

Even earlier than all this, in 1982, she sent me a poem about a small lamp by the Great Wall glittering in the vast darkness. The glittering was also, perhaps, the eyes of birds. In those days, Liu Xia had a portrait of the American poet Sylvia Plath above her bed. So we talked about Plaths three suicide attempts. The woman who could eat men like air played a game of death. What if she had died accidentally; what if there had been a gas leak; what if the gas repairman was just half an hour too late? Talking, we giggled for no good reason.

Tears fell while we were still laughing. We were young, and we could laugh at death, whether we wanted to criticize it or praise it, we laughed and laughed, with wisdom or dementia, uncontrollably. Perhaps human beings should give up language, become birds and fly into the sky freely, stopping on trees to feed on insects when hungrywouldnt that be enough? But then in 1989, the violence at Tiananmen broke out, and many young people were killed. They might have, like us, at one point, laughed at death. Their souls climbed out of their bodies, which were perforated by bullets, like unseeable birds and flew before the eyes of Liu Xia and Liu Xiaobo. And so, through sleepless nights, the two were tied together, nested in each others souls.