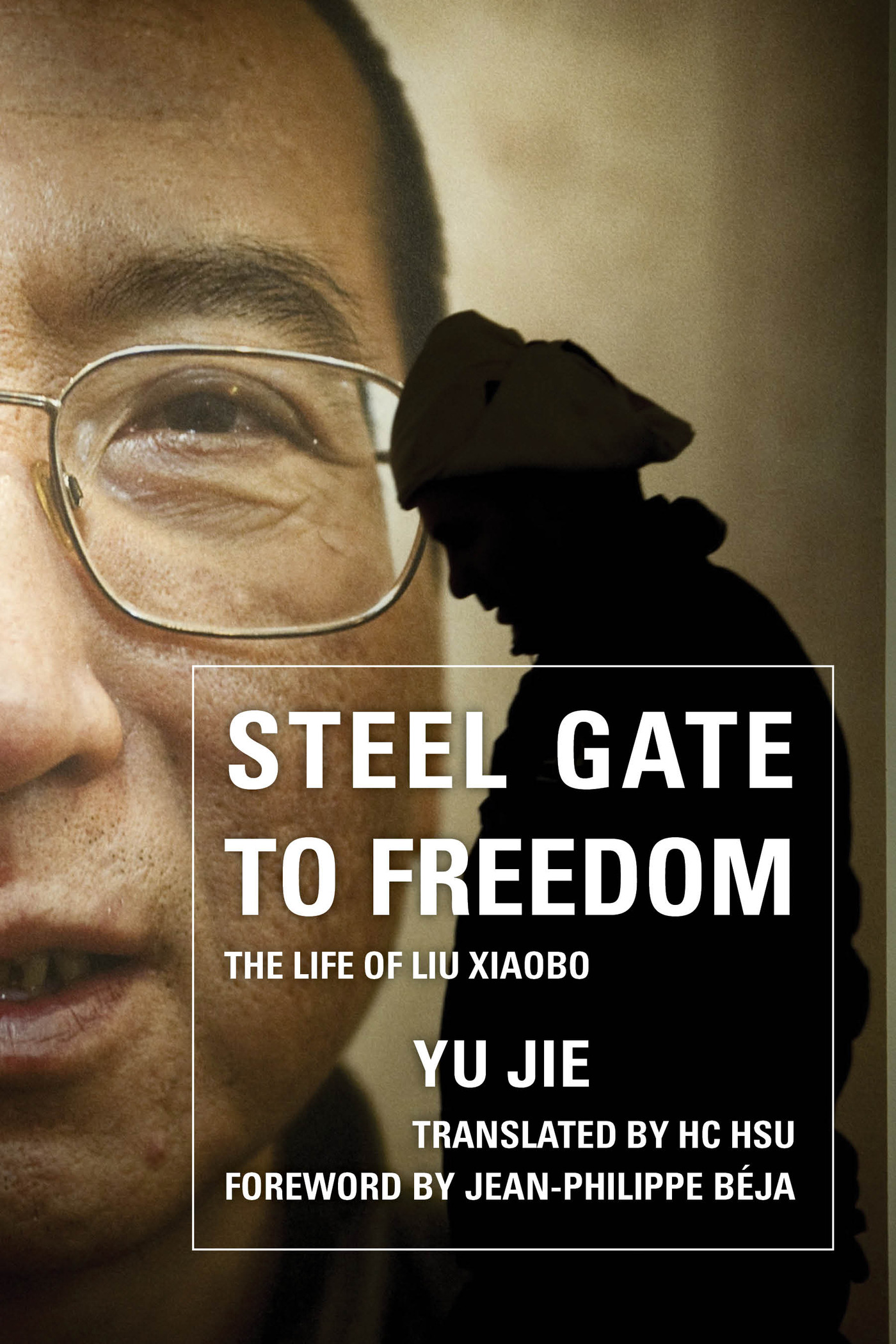

Steel Gate to Freedom

Steel Gate to Freedom

The Life of Liu Xiaobo

Yu Jie

Translated by HC Hsu

ROWMAN & LITTLEFIELD

Lanham Boulder New York London

Published by Rowman & Littlefield

A wholly owned subsidiary of

The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc.

4501 Forbes Boulevard, Suite 200, Lanham, Maryland 20706

www.rowman.com

Unit A, Whitacre Mews, 26-34 Stannary Street, London SE11 4AB,

United Kingdom

Copyright 2015 by Rowman & Littlefield

All photos courtesy of Yu Jie.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote passages in a review.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Information Available

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Yu, Jie, 1973

[Liu Xiaobo zhuan. English]

Steel gate to freedom : the life of Liu Xiaobo / Yu Jie ; translated by HC Hsu.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-4422-3713-1 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN 978-1-4422-3714-8 (electronic)

1. Liu, Xiaobo, 1955 2. Political prisonersChinaBiography. 3. DissentersChinaBiography. 4. Nobel Prize winnersBiography. I. Hsu, H. C., 1982 II. Title. III. Title: Life of Liu Xiaobo.

CT1828.L595Y82513 2015

365'.45092dc23

[B]

2015008574

TM The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

TM The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

Printed in the United States of America

Foreword

Jean-Philippe Bja

When Liu Xiaobo was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in October 2010, journalists and scholars of China were very much aware of his numerous writings on politics. Some remembered the black horse who shook up the literary scene in 1986 with his iconoclastic piece denouncing Chinas contemporary literature at a time permeated by a self-congratulatory air. But no one knew who the real Liu Xiaobo was or understood how the 1980s maverick had become the astute political analyst who drew up a thorough diagnosis of the ills of the current Chinese regime.

This book by fellow dissident and long-time friend Yu Jie fills that gap. Yu has known Liu for over ten years. In the years before his arrest, almost every time I had lunch or dinner with Liu, Yu was there, taking part in the discussion, poring over the fine points. A political dissident and fine writer himself, Yu had attracted Lius attention with the publication of his first book.

Its important to note that since his release from reeducation through labor in 1999, Liu has assumed a central role in the Chinese dissident movement. So it was only natural newly christened dissidents should gravitate toward him. That is what happened to Yu. A long and deep friendship developed, but one would be wrong to think Yus critical spirit is dampened here.

As someone deeply respected by and who deeply respects Liu, Yu is in the best position to write his biography. He knows most of Lius friends, his wife Liu Xia, and his family. A literary critic like Liu, Yu has a profound empathy with Lius work. In this book, partly based on interviews with numerous acquaintances in China as well as the United States, Yu takes the reader on a journey through the roaring eighties, a decade that, for its ups and downs, was marked by a renewed curiosity for the outside world and experimentation in all manners of Chinese daily life. Liu enthusiastically took part in this renaissance. He founded a poetry journal at his alma mater, Jilin University, and, on arriving at the epicenter of Beijing, published scathing articles, most notably in China, a new review started by Ding Ling, criticizing the inability of intellectuals to have distinct personalities. His book Critique of Choice: Conversations with Li Zehou, a criticism of the influential intellectual at the time, sounded a loud ring through the public. Furthermore, the confident young man didnt hesitate taking contemporary Chinese writers penchant for self-pity to task: in Reflection without Escape: The Picture of the Intellectual in Recent Fiction, Liu panned influential writers and filmmakers for airbrushing intellectualsthemselvesand making them up like Christ figures at a time when scar literature presented them as heroic victims of the Cultural Revolution. When authorities shut down China, Liu became furious and launched a petition. It was his first time as a protest organizer, and the experience would help him in his later endeavors.

Yu rightly describes Liu Xiaobo as a prime example of Northeastern Chinese, who have a tough exterior and unyielding interior,... [are] loud and never get cold feet,... [are] bright and open and value camaraderie over the law, and... love making friends. There is a gangster attitude to their way of life, and this was already apparent in Liu in his early years. The young child raised by a stern father and a doting mother (a situation quite common in Chinese families, as Yu notes) cultivated a strong fighting spirit that found an expression during the Cultural Revolution. I am grateful for the Cultural Revolution. I was a kid then. I could do whatever I wanted. My parents were off revolutionizing, schools stopped, and I was for a time able to be rid of the constraints of an education, to do whatever I wanted to do, to play, to fight. I lived a happy life. This period of his life no doubt reinforced Lius individualism and deepened his hunger for self-achievement.

This personality further manifested itself when, during the eighties, Liuwho had been married early to Tao Li, the daughter of an intellectual familyrefused to be bound by the trappings of marriage. As Yu observes, he was always surrounded by pretty girls and was a womanizer. This attitude was also typical of the eighties when, after years of Cultural Revolution puritanism, the sexual revolution was regarded as a healthy reaction against Maos reign.

During this decade, Liu, fascinated by Nietzsche, was an ultra-individualist. His writings were meant to be shocking, and they did what they set out to do. It is in this context his declaration that Chinese writers... cant write creatively themselvesthey simply dont have the abilitybecause their very lives dont belong to them, which so stunned progressive audiences, should be interpreted: Liu didnt shy from agitating mainstream opinion. His heretical views on literature made him a celebrity in the literary scene, and young people used to fight for a seat to attend the slightly stuttering stars talks on the most prestigious Chinese campuses. Though thought provoking, his individualism kept him from getting directly involved in politics.

Like most successful Chinese intellectuals in the 1980s, Liu was invited to lecture abroad, and he spent three months in Norway, where he was quite disappointed by the countrys quiet serenity, and in the United States. But in contrast to his colleagues, as the 1989 pro-democracy movement fermented in Beijing, he became restless and, after careful consideration, decided to go home to take part in this historical event. He spent all his time at Tiananmen Square, living with the students but also not holding back on criticizing them. Despite, or because of, his forthrightness, he earned their esteem and admiration. His hunger strike and the role he played in persuading the students to leave the square helped change the intellectual provocateur into a reasoned political actor.

Next page

TM The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

TM The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.