PERRY LINK is Emeritus Professor of East Asian Studies at Princeton University, specializing in modern Chinese literature and Chinese language. He is currently Chancellorial Chair for Teaching Across Disciplines at the University of California, Riverside. Along with Andrew J. Nathan, Link edited and translated The Tiananmen Papers, a compilation of leaked Chinese government documents detailing Beijings internal response to the 1989 democracy protests. Together with Tienchi-Martin Liao and Liu Xia, he is editing No Enemies, No Hatred, a collection of essays and poems by Liu Xiaobo that will appear in 2011 from Harvard University Press.

THIS IS A NEW YORK REVIEW E-BOOK ORIGINAL

PUBLISHED BY THE NEW YORK REVIEW OF BOOKS

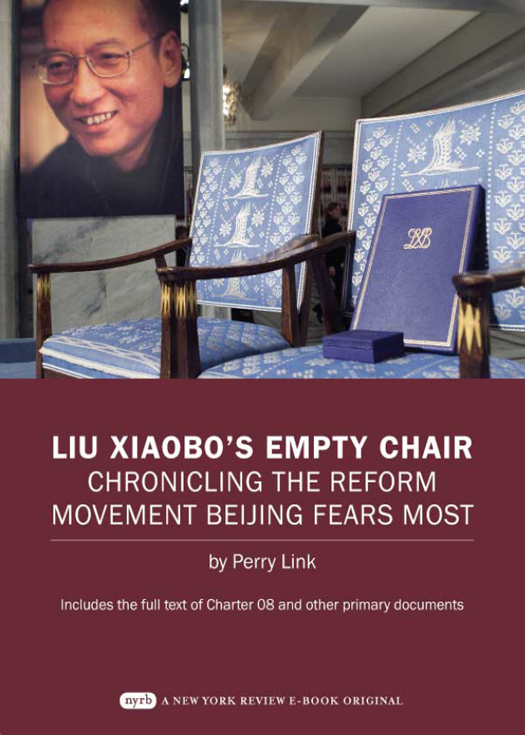

LIU XIAOBOS EMPTY CHAIR

Chronicling the Reform Movement Beijing Fears Most

By Perry Link

Copyright 2011 by Perry Link

Copyright 2011 by NYREV, Inc.

All Rights Reserved.

This electronic edition first published in 2011

in the United States of America by

The New York Review of Books

435 Hudson Street

New York, NY 10014

www.nyrb.com

eISBN: 978-1-59017-477-7

This book draws on texts written or translated by Perry Link around the time the events discussed in them took place. Links translation of Charter 08 and a version of the letter by Mo Shaoping were published in The New York Review of Books. Parts of appeared, in different form, on the NYRblog, the Reviews online supplement.

v3.1

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

Who is Liu Xiaobo?

On the night of December 8, 2008, police knocked on the door of the literary critic Liu Xiaobo in Beijing and took him away. He has not been home since. Over a year later, a prison sentence was finally announced: eleven years for incitement to subvert state power in his writings, including, above all, a citizens manifesto that he and others had been drafting called Charter 08. Released the day after Lius arrest, Charter 08 is primarily an appeal for such uncontroversial values as human rights, equality, and the rule of law. But it is also the first public statement in the history of the Peoples Republic of China to call for an end to one-party rule. That it was signed by more than 12,000 Chinese citizens and has the support of countless others who fear the consequences of public endorsement has made it all the more threatening to Chinas rulers. By agreeing to be the charters primary sponsor, Liu was taking extraordinary risks. Yet for anyone who knows Liu and his work, this was entirely consistent with his unceasing and uncompromising efforts to create a better China.

Born in 1955 in Changchun, a city in the northeastern province of Jilin, Liu Xiaobo was eleven years old when Mao Zedong closed his schoolalong with every other school in the countryso that youngsters could go into society to oppose revisionism, sweep away freaks and monsters, and in other ways join in Maos Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution. In retrospect, Liu believes that this was good for him. His years of lost schooling, he told Geremie Barm, a Sinologist at the Australian National University, allowed him a temporary emancipation from the mind-closing indoctrination of Maoist education; they also gave him time to read books, beginning with Marx, Engels, and the modern Chinese writer Lu Xun. But the most important lesson came from the pervasive cynicism and chaos of Chinese society during the Cultural Revolution, which taught him that he would have to think for himself. Where else, after all, could he turn? This general experience resembled that of several other writers of Lius generation. Hu Ping, Su Xiaokang, Zheng Yi, Bei Dao, Zhong Acheng, Jiang Qisheng, and many others forged their lifelong habits of independent thought during these years. For some, like Liu himself, this led to a questioning of the political system as a whole. Mao had preached that rebellion is justified, but this is hardly the way the Chairman thought it should happen.

After Maos death in 1976, Chinese universities reopened, and in 1978 Liu enrolled at Jilin University, where he was awarded a degree in Chinese literature four years later. He then went to Beijing Normal University where he continued to study Chinese literature and received a Ph.D. in 1988. In graduate school, Liu was already well known for his iconoclastic writings in literary journals and his blunt pronouncements at conferences. Seemingly no one escaped his withering criticism: Maoist writers like Hao Ran, he asserted, were no better than hired guns; post-Mao literary stars like Wang Meng were but clever equivocators; roots-seeking writers like Han Shaogong and Zheng Yi made the mistake of thinking China had deep cultural resources that were worth tapping. Even speak-for-the-people heroes like Liu Binyan were too ready to embrace good leaders like Hu Yaobang, the reform-minded general secretary of the Communist Party who was forced to resign and whose death in 1989 sparked the Tiananmen Square student movement. (In Liu Xiaobos view, Hu Yaobang may have been the most open-minded in the Communist Parys top leadership, but China needed reform more radical than what he offered, and to pin hopes on such a figure was a diversion.)

Although Liu seemed bent on making people uncomfortable, he seldom inspired true enmity. There was something endearing about his unadorned honesty, and his opinions, while perhaps unpleasant to hear, were also hard to refute. He dressed plainly and was utterly unpretentious. His verbal fusillades were delivered in a famous stutter. I can sum up whats wrong with Chinese writers in one sentence, he wrote in 1986. They cant write creativelythey simply dont have the abilitybecause their very lives dont belong to them.

He went further, though, than criticizing the political indoctrination and self-censorship that had infected the thinking of most of his contemporaries. Well before the Communist revolution, he argued, Chinese writers had been too preoccupied with China: its society, its character, its destiny. They were unable to go beyond these problems to address the fundamental human condition. Liu cited Lu Xun (18811936), who is widely seen as the greatest Chinese writer of the twentieth century. Lu Xuns early stories were elegant and incisive exposs of Chinas social maladies: inequality, moral callousness, hypocrisy, superstition, and cruelty. But in Lius analysis, even this great writer ultimately failed to find any transcendental values to help him continue and in the final years of his life descended into mediocre polemics.

In 1988 Liu wrote that perhaps my personality means I will crash into brick walls wherever I go. Shortly afterward he was a visiting scholar at the University of Oslo, in the city where twenty-two years later he would receive the Nobel Peace Prize, but on this trip he was still colliding with walls. He attended a conference on modern Chinese film, which he found agonizingly boring. He was disappointed to learn that European Sinologists could barely speak Chinese (traditional Western Sinology is based on reading and translation, not speaking) and was further irritated at how willing they were to accept Chinese government statements at face value. He offered the view that, of these Sinologists, 98 percent are useless. It made him an awkward guest.

After Olso he went to Columbia University, where he encountered critical theory and learned that its dominant strain, at least at Columbia, was postcolonialism. People expected him, as a visitor from China, to fit in by representing their notion of the the subalternChinese who were regarded as inferior by dominant foreign powers. They also expected him to resist the discursive hegemony of the metropole. Liu wondered why people in New York were telling him how it felt to be Chinese. Shouldnt it be the other way around? Was postcolonialism itself a kind of intellectual colonialism? In China he had seen Western values as tools for measuring Chinas progress, but now he concluded that in using Western values to criticize Chinese culture I have been attacking ossified culture with only slightly less ossified weapons. Again the awkward guest, Liu concluded in the spring of 1989 that no matter how strenuously Western intellectuals try to negate colonial expansionism and the white mans sense of superiority, when faced with other nations Westerners cannot help feeling superior.