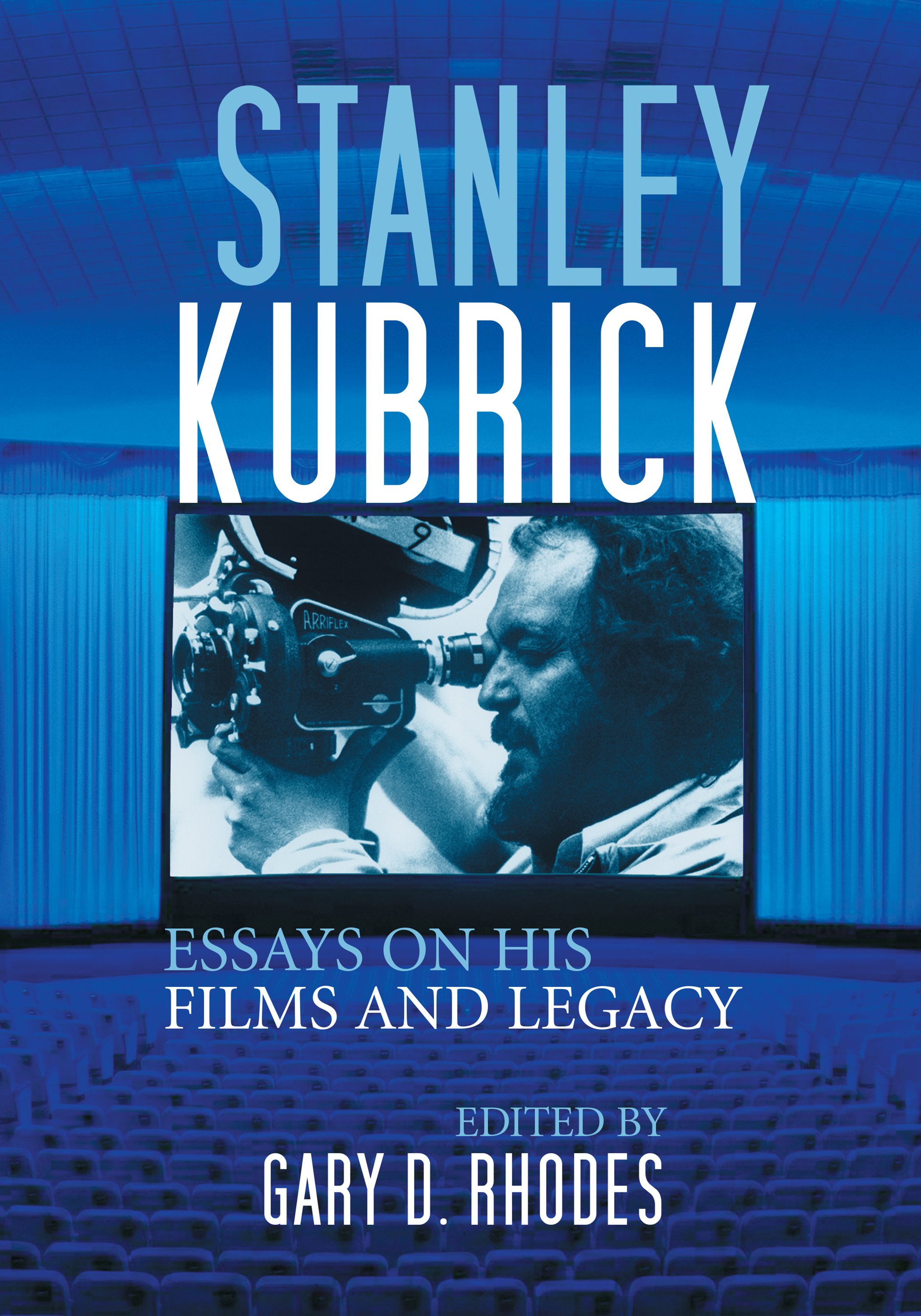

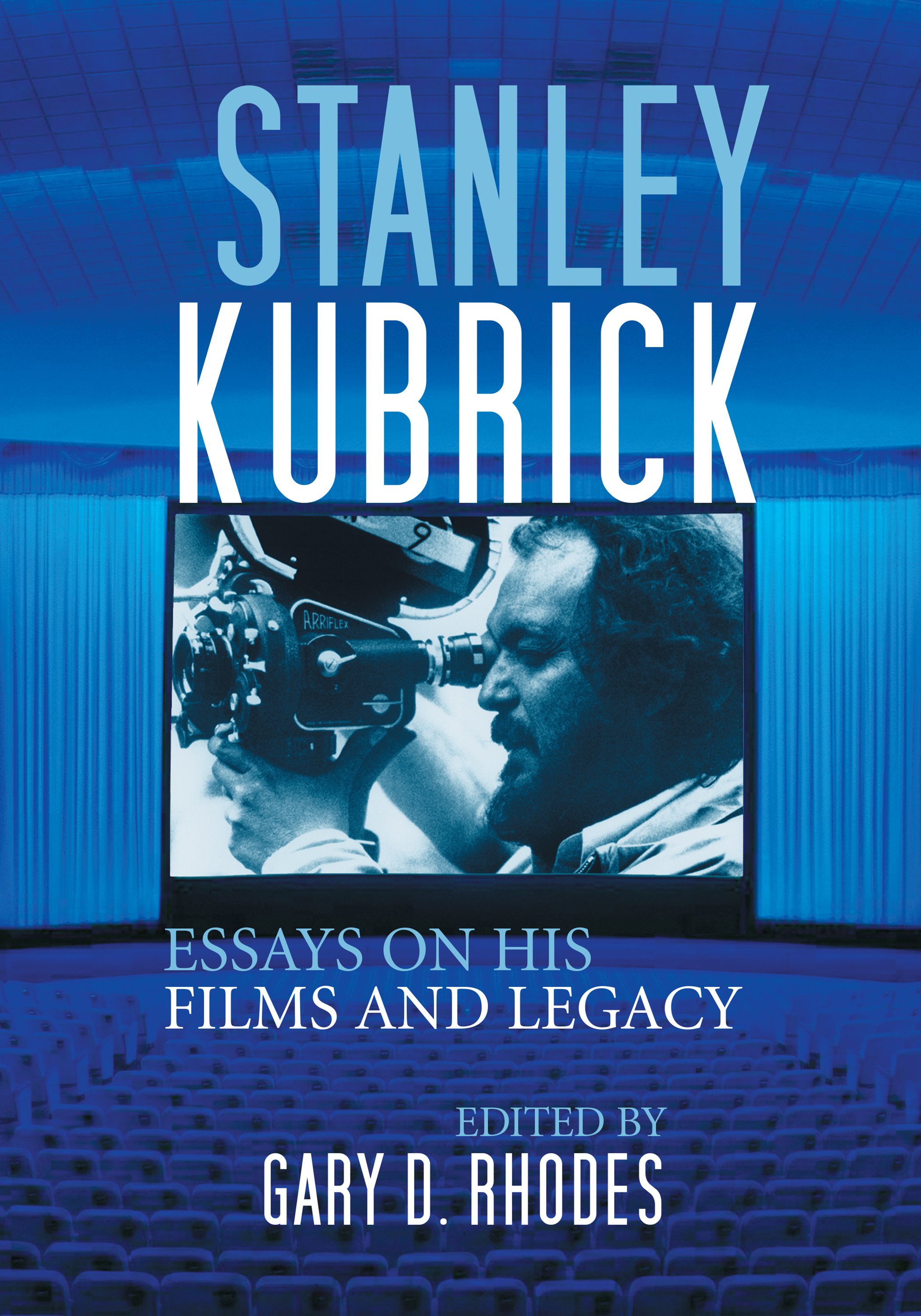

Stanley Kubrick

Essays on His Films and Legacy

Edited by Gary D. Rhodes

McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers

Jefferson, North Carolina

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGUING DATA ARE AVAILABLE

BRITISH LIBRARY CATALOGUING DATA ARE AVAILABLE

e-ISBN: 978-1-4766-1050-4

2008 Gary D. Rhodes. All rights reserved

No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying or recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

On the cover: Stanley Kubrick shooting handheld with an Arriflex camera (background image 2007 Creatas)

McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers

Box 611, Jefferson, North Carolina 28640

www.mcfarlandpub.com

For Joseph Turkel.

At age ten, I thought he was the scariest man alive,

thanks to his amazing performance in The Shining (1980).

Befriending him some fifteen years later,

I realized he is one of the kindest

and most talented gentlemen on this planet.

Introduction

Gary D. Rhodes

My memories of high school are plentiful, but some of the first that enter my mind are the wonderful times I had watching films with my friend Devin Williams. Thanks to the wonders of the VCR, we scrutinized the important works of Chaplin, Dreyer, Murnau, Lang, and many others. But it was always Stanley Kubrick who captivated us the most. We pondered endlessly over what 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) meant, and buckled over laughing at the dark comedy in Dr. Strangelove (1964). The 1921 photo of Jack Torrance at the conclusion of The Shining (1980) enthralled us. And our countless viewings of A Clockwork Orange (1971) were matched only by countless playbacks of its soundtrack album.

Along with our interest in Kubricks filmography, we were enthralled by Kubrick the man. Perhaps it was the fact we felt his presence through his absence; after all, he was the man whom movie magazines had dubbed a recluse. For example, Devin and I read somewhere that he refused to drive an automobile and that he required his chauffeur to drive exceedingly slowly. Elsewhere we read that he loved to burn down the road at top speed behind the wheel of his sports car. These contradictions only served to increase our fascination.

Soon we became aware of the groundbreaking work of Michel Ciment, as well as Thomas Allen Nelsons illuminating text Kubrick: Inside a Film Artists Maze (Indiana UP, 1982). And of course we anxiously awaited any word of a new Kubrick film, ever hopeful that his filmography would continue to grow. Our long wait began with the release of Full Metal Jacket (1987).

In the many years since that time, my interest in Kubrick continued, and on more than one occasion I taught a course on his films (as well as a course devoted solely to 2001: A Space Odyssey) at my alma mater, the University of Oklahoma. During that same period, I befriended Joseph Turkel, who worked in three of Kubricks films and who kindly gave a wonderful speech on the filmmaker in Oklahoma. The passage of time has also allowed me to learn much from the ever-increasing body of Kubrick literature: the biographical work of John Baxter and Vincent LoBrutto, the theoretical inquiries of Michel Chion, Randy Rasmussen, and Alexander Walker, the photographic analysis of Rainer Crone, and the rather staggering collection of Kubricks archival materials that Alison Castle edited for Taschen in 2005.

The goal of this current anthology is not to conclude any debates on Kubrick, but rather to participate in the ongoingindeed, expandingconversation about his life and work. Indeed, this book does not cover key films like Lolita (1962), Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb (1964) and Full Metal Jacket (1987) in any depth. At the same time, a number of essays do examine issues that have previously received very limited coverage, such as Kubricks photography and newsreels.

Collectively, the seventeen selected essays in this anthology represent analyses of the narratives, genres, themes, visuals, and soundtracks that mark much of Kubricks work. Without necessarily wanting to force categorical judgment onto Kubricks canon, I have structured these essays into four sections for the ease of the reader: EARLY WORKS, MAJOR WORKS, Eyes Wide Shut (1999): A CASE STUDY, and KUBRICKS LEGACY.

EARLY WORKS opens with Philippe Mathers fascinating and monumental examination of Kubricks photography for Look magazine, which is followed by Marina Burkes exploration of Kubricks generally overlooked and rarely seen newsreels. Charles Bane discusses Fear and Desire (1953), connecting it to Kubricks Paths of Glory (1957). Tony Williams offers a valuable examination of the dream landscape of Killers Kiss (1955), a film that, along with The Killing (1956), is considered by Hugh Manon in his engaging analysis of Kubrick and film noir.

Eric Eatons revelatory essay on Paths of Glory places the film truly at the vanguard of Kubricks MAJOR WORKS. Reynold Humphries offers an important analysis on the much-maligned Spartacus (1960). My own essay attempts to unravel and interpret layers of surveillance in 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), while Kate McQuiston investigates the music in A Clockwork Orange (1971) in great depth. Homay King offers a deft examination of spectatorship and the zoom lens in Barry Lyndon (1975), and Jarrell D. Wright reconsiders genre and fidelity in The Shining (1980).

Jack Nicholson (center, bottom) in the photograph dated 1921 that appears at the conclusion ofThe Shining(1980).

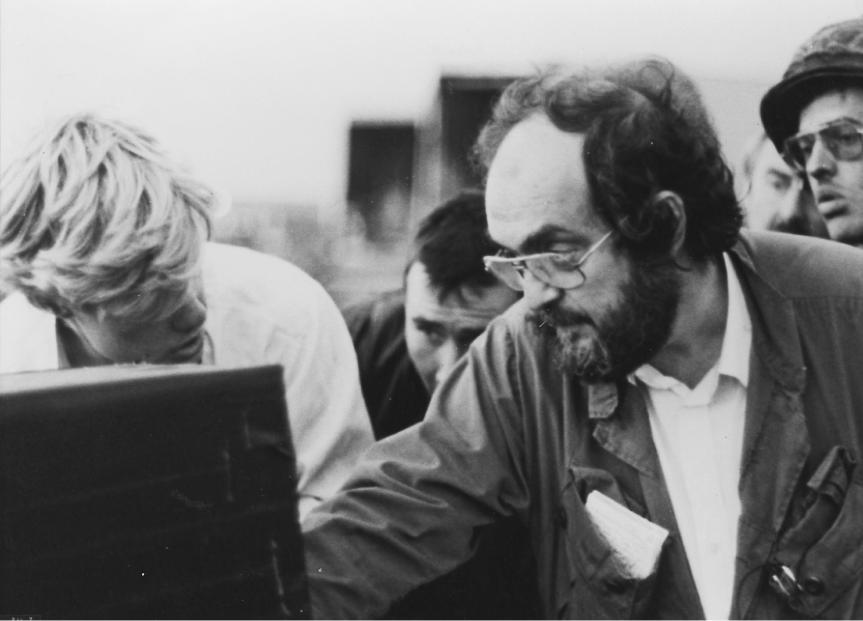

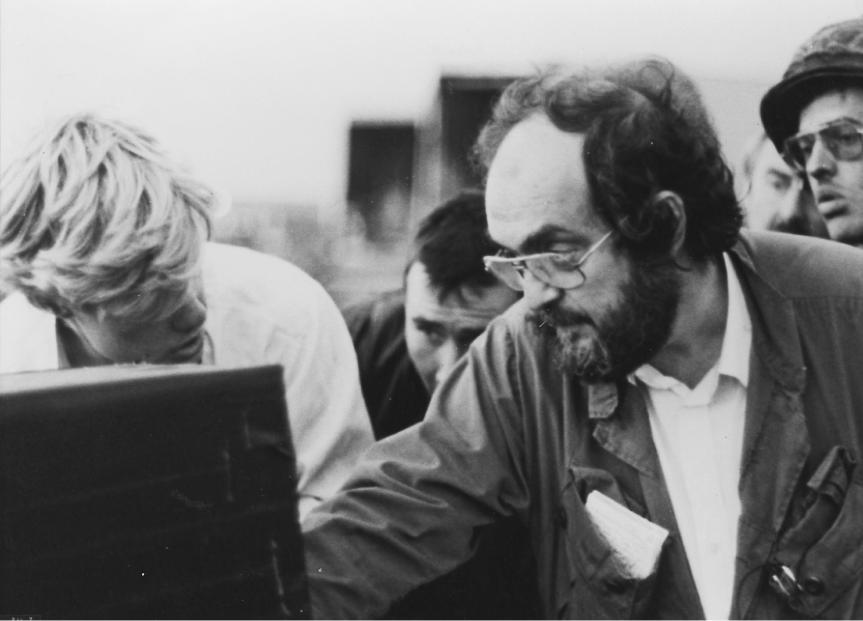

Kubrick working on Full Metal Jacket in 1987.

With regard to Eyes Wide Shut (1999), I am reminded that Jan Harlan, Kubricks executive producer and brother-in-law, told me in 2007 that Kubrick believed it was his greatest film. Some audiences and critics might well disagree with that assessment, though we are still at an early stage in the history of its reception. Certainly we can say that it has not received as much analysis as Kubricks other major works, largely because of its relatively recent date of release. Our case study of the film offers four very different examinations of Eyes Wide Shut. Randolph Jordan addresses the issue of sound, while Lindiwe Dovey investigates its representation of gender. Using Bakhtin as a key paradigm, Miriam Jordan and Julian Jason Haladyn examine the films use of the carnivalesque. Phillip Sipioras engaging phenomenological inquiry concludes the quartet of essays on a film that deserves continued analysis.

The final section of the book, KUBRICKS LEGACY, offers two essays that investigate aspects of the filmmakers ongoing impact. Scott Lorens essay on 2001: A Space Odyssey connects his discussion of the posthuman subject to Spielbergs Artificial Intelligence: A.I. (2001), a film based on Kubricks unproduced ideas and released two years after his death. Finally, Robert J. E. Simpsons essay Whose Stanley Kubrick? tackles the mythology and ownership of the Kubrick image as constructed during his lifetime and in the years since his demise.

Next page