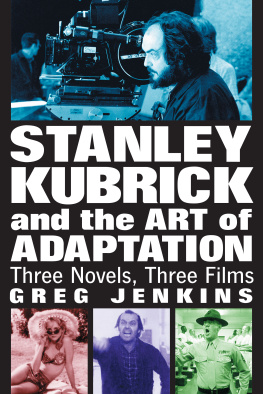

Stanley Kubrick

and the Art of Adaptation

Three Novels, Three Films

Greg Jenkins

McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers

Jefferson, North Carolina

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGUING DATA ARE AVAILABLE

BRITISH LIBRARY CATALOGUING DATA ARE AVAILABLE

e-ISBN: 978-1-4766-0884-6

1997 Greg Jenkins. All rights reserved

No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying or recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

On the cover: Stanley Kubrick on the set of The Shining, 1980 (Warner Brothers/Photofest); Sue Lyon in Lolita, 1962 (MGM/Photofest); Jack Nicholson in The Shining; and R. Lee Ermey in Full Metal Jacket, 1987 (Warner Brothers/Photofest)

McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers

Box 611, Jefferson, North Carolina 28640

www.mcfarlandpub.com

Adaptation is a peculiar form of discourse but not an unthinkable one.

Dudley Andrew

Chapter 1

Introduction

Adapting a best-seller for the movies is like carving flesh down to the bone, Richard Corliss has written. You keep the skeleton, then apply rouge and silicone until the creature looks human (Wrong Arm 58). The assertion, which one presumes is not strictly tied to a novels sales, has much to recommend it: it is terse, witty, and memorably grotesque. It even contains a substantial measure of truth. But, as I will establish herein, it is a simplistic description of a fairly intricate process; worse, in some specific situations, it is plainly inaccurate.

My object in this book is to explore the long-standing problem of film adaptation. More exactly, I mean to illustrate how selected narratives become altered as they pass from novel to film form and to assay the effects of these alterations. I will dwell mainly on changes in the characters and in narrative structure, since this direction is indicated by the relevant literature, but I will also attend to matters of style, scope, pace, mood, and meaning. My approach, as I explain below, is rhetorical.

I have chosen to focus on three films directed by Stanley KubrickLolita, The Shining, and Full MetalJacketand on the novels that inspired them. My reasons for gravitating to Kubrick are straightforward. He is, first, an eminently successful director-screenwriter, the subject of several books and numberless reviews and articles. Norman Kagan submits that Kubricks oeuvre holds great critical interest, both in terms of the films ideas and comments about our culture and society, and in their own aesthetic concerns (189). Thomas Nelson contends that Kubricks films embody such a stylistic and conceptual density that they are capable of stimulating even the most parochial of critical tastes (1). Gene Phillips notes that Kubrick has steadily built a reputation as a filmmaker of international importance (30). With some finality, Alexander Walker has pronounced him a major artist (Kubrick Directs 44).

Second, Kubrick has evidenced a marked interest in adaptation. As of 1993, he has directed 12 commercial films: Fear and Desire (1953), Killers Kiss (1955), TheKilling (1956), Paths of Glory (1957), Spartacus (1960), Lolita (1961), Dr. Strangelove, or How I Learned to StopWorrying and Love the Bomb (1963), 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), A Clockwork Orange (1971), Barry Lyndon (1975), The Shining (1980), and Full Metal Jacket (1987). All but the first two are adapted. Of the adaptations, all but 2001, which is derived from Arthur C. Clarkes short story The Sentinel, are based on novels (Kolker 4005). Moreover, Kubrick has been forthcoming in divulging his views of the adaptive art.

Third, as a circle of onlookers univocally attests, Kubricks ability to control and safeguard his projects is exceptional among directors. As long ago as 1966, Jeremy Bernstein wrote: Kubrick supervises every aspect of his films, from selecting costumes to choosing the incidental music (91). Walker discloses that, following the frustrating experience of Spartacus, wherein actor Kirk Douglas had ultimate authority, Kubrick has never relinquished the power of decision-making to anyone (Kubrick Directs 27). Phillips observes that Kubrick has full artistic control over his films, and that he guides them from the earliest stages of planning and scripting through the final snap of the editors shears (30). Martha Duffy and Richard Schickel confirm that he is unencumbered by studio advice or interference (75), and Kagan proclaims him an auteur critics dream:

He writes, shoots, directs, edits, and often handles his own publicity. He has, in fact, sought ever more control as his career [has] progressed; his films are probably as close to personal works of art as any in the commercial cinema [xiii].

Kubricks estimable power is a point to be remembered since, if he were less commanding, his beliefs concerning adaptation would ring hollow: he would be less able to act on them.

I am aware of just one extended work, a 1982 dissertation by Judy Lee Kinney, that analyzes Kubricks films expressly as adaptations. (Many shorter studies grapple with the issue, particularly as regards Lolita.) While Kinneys treatment is informed and helpful, it is not definitive, and, to a degree, I justify my own effort by enumerating some of the differences between her study and mine:

1.Kinneys literature review, which mentions George Bluestone, Andr Bazin, and a few others, is quite frugal. I furnish a wider and more detailed conspectus of how adaptation has been understood, recounting statements made by approximately two dozen diverse sources.

2.She discusses six films; I discuss three (including Full Metal Jacket, which of course she could not). Whereas her discussion claims greater breadth, mine offers increased depth; my readings are closer.

3.Kinney touches on the novels just lightly. Since, after all, they represent the root of the adaptive process, I bring them more dedicated attention.

Insofar as I view the craggy terrain of adaptation through a limiting windowmy perspective is rhetorical and restricted to three films directed by one personI must concede that none of my findings assumes the form of a universal law. Then again, as the literature makes clear, the topic simply does not lend itself to edicts. Still, in the course of my investigation, a network of trends, which I summarize in my concluding chapter, does emerge. I trust that these trends reveal something fundamental about Stanley Kubricks adaptive technique, and, by inference, provide a glimmer of insight into the knotty, persistent problem of adaptation at large.

The Problem of Adaptation

Not everyone agrees that adaptation is a problem; some have sought (I paraphrase Joyce) to refine the very concept of adaptation out of existence. William Horne, for instance, spreads doubt on the underlying premise of originality, without which adaptation is rendered meaningless. Throughout history, he notes, artists have commonly appropriated available materials and recast them into new incarnations. The tragedians of ancient GreeceAeschylus, Euripidesfashioned their plays from traditional myths (Horne 21). During the Renaissance and Neoclassical periods, uncounted European writers borrowed freely and openly from their predecessors (22). Even Coleridges strikingly distinctive Kubla Khan has its origins in the poets omnivorous reading (23). One apprehends that, by this reasoning, true originality would mean the creation of a work totally incomprehensible to all but its creator (2324). Ergo, if nothing is truly original, then nothing is truly adapted.