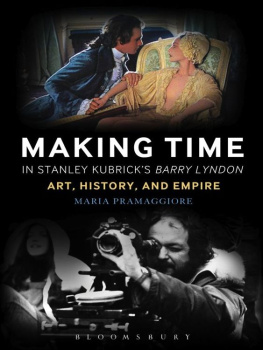

Making Time in Stanley Kubricks Barry Lyndon

Making Time in Stanley Kubricks Barry Lyndon

Art, History, and Empire

Maria Pramaggiore

Bloomsbury Academic

An imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing Inc

Contents

I consider myself extremely fortunate to have so many friends and colleagues who patiently tolerated my obsession with all things Barry Lyndon, which, at times, has included incessant references to Kubricks work and the oversharing of salacious details surrounding Ryan ONeals career.

First, I thank the archivists and librarians who helped me to see the materials related to Kubricks film. Leith Adams made my 2006 visit to the Warner Brothers archive both enjoyable and productive. Between 2009 and 2013, I was able to visit the Stanley Kubrick Archive at the London College of Communication on numerous occasions. My colleagues there became friends and I thank them profusely for their kindness. Foremost among them are Richard Daniels and Wendy Russell, who inspired me with their love of the archive and gently corrected my errors and misconceptions. Monica Lilley and Joanna Norledge were also part of that wonderful support team. I thank Marihelen Stringham, Cindy Levine, Darby Orcutt, and the staff of the Interlibrary loan office at DH Hill library at North Carolina State University, who always supported my research with professionalism and good humor.

Some of the friends who have offered ideas, guidance, friendship, and sustenance of all kinds along the way include Gwenda Young, Jim Morrison, Diane Negra, Joe Gomez, Tom Gunning, Toby Miller, Steve Elworth, Ora Gelley, Inga Pollmann, Bob Kolker, Eibhear Walshe, Lance Pettit, Gregg Flaxman, Markos Hadjioannou, Deb Wyrick, Shilyh Warren, Jean Walton, Mary Capello, Bella Honess Roe, Bob Burgoyne, Dana Bartelt, and Amelie Hastie.

I offer special thanks to Tony Harrison, the worlds best department head, for his support and friendship.

While I have drawn more than I will ever know from these friends and colleagues, all errors, oversights, and omissions remain my own.

I presented work related to this book at conferences and invited talks, and I gratefully acknowledge the individuals who gave me opportunities to share my work: Ruth Barton, who organized the Screening Irish America Conference at University College Dublin (2007), Jim Morrison, who organized the panel on the long take at the New Orleans SCMS Conference (2011), and Diane Negra, who gathered the panel on transnational Irishness at SCMS in Boston (2012). Gwenda Young invited me to present my work at the University College Cork Seminar (2009); Bella Honess Roe invited me to present work at the University of Surrey (2011); and Inga Pollmann asked me to speak at the Triangle Film Salon (2012). I thank those whom I met over the course of the project and who kindly included early versions of this material in their books: Tatjana Ljulic and Richard Daniels, and Constantin Parvulescu and Robert Rosenstone.

I gratefully acknowledge the Fulbright fellowship that brought me to Cork in 2007 for a semester that provided the impetus for the project. The College of Humanities and Social Sciences and the English Department at NC State University supported several trips to the Stanley Kubrick Archive in London.

I thank President Philip Nolan and my colleagues in Media Studies at the National University of Ireland MaynoothStephanie Rains, Gavan Titley, Jeneen Naji, Kylie Jarrett, Anne OBrien, Denis Condon, and Anne Byrne who graciously supported my leave in the fall of 2013 so that I could finish the manuscript and welcomed me to Maynooth with the utmost courtesy and collegiality.

Four anonymous readers were instrumental in helping me to shape my argument. Ryan Craver provided indispensable assistance in locating images.

Katie Gallof at Bloomsbury has been unflagging in her support, from start to finish. She gave me the gift of time, friendship, and autonomy: true luxuries for academic writers. Mary Al-Sayed ensured that the production process was painless.

Good friends who constantly reminded me that the world does not revolve around Barry Lyndon include Beth Hardin, Deb Wyrick, Ellen Garrett, Kim Loudermilk, Annie Merrill, Sharon Joffe, Dorianne Laux, Melissa Rossi, Francesca Talenti, Andrea Gomez, Susan Miller-Cochran, Val Coogan, Anne OMalley, Elaine Orr, Shanti Ferguson, Amanda Roop, Jenn Gerteisen Marks, Leslie Blackwell, Celeste Pearson, Lakshmi Om, Padma Om, Ganesh Om, and Satya Om. I thank Chandra Om, who always inspires by example.

A film like Barry Lyndon, which deals with generational loss, cannot fail to bring that subject to consciousness. I regret that I wasnt able to discuss this film with my father, Alfred, who knew more about movies than I ever will. My mother, Jeanne Lacy Pramaggiore, prized her Irish roots and would have offered me a great deal to think about if I had had the opportunity to hear her thoughts. My sister Anne never fails to embrace my work and to support my sometimes unorthodox choices. My nephew Jack, with his preternatural wisdom and enormous heart, offers me hope for the future.

Tom Wallis, who has an astonishing ability to remain grounded no matter what I throw at himfrom endless looping of the Sarabande to bringing home one more rescued dog to transatlantic relocationstands at the center of every frame.

Ireland mustnt be such a bad place so, if the Yanks want to come to Ireland to do their filming.

Johnnypateenmike, The Cripple of Inishmaan

In an interview aired on May 2, 2013 on National Public Radios Morning Edition program, David Chase, the creator of the popular HBO television series The Sopranos (19992007), shared his list of must-see movies with host Steve Inskeep. During their discussion, Inskeep mentions that Chase has included several famous film directors on his list, but has not always recommended their best-known films. A case in point is Stanley Kubricks Barry Lyndon (1975). Chase agrees with Inskeep, then expresses his admiration for the films Victorian complexity and explains his particular fondness for its protagonist: the guy is a rapscallion, and a rake, and a kind of a scumbag (Chase and Inskeep). Remarking upon the importance of duels in Barry Lyndon, Chase continues: whats great about it is that, with all this violence, theres this overlay of the most civilized conduct, you know, with the handkerchief inside the sleeve (Chase and Inskeep).had to go by. But of course, the code is ridiculous: its a code among sociopaths (Chase and Inskeep).

Having spent several years thinking about Stanley Kubricks Barry Lyndon, I listened to this exchange with great interest. The discussion brought into relief some of the political and aesthetic questions that initially drew me to the film. One central question that the film raises for me is: what does the world look like when an entire society, indeed a burgeoning global empire rather than a troubling, self-destructive gangster subculture, is governed by a code among sociopaths?

While many films, novels, and television programs made before and after Barry Lyndon envision this scenario as an apocalyptic breakdown of social order, Kubricks unique contribution to the cinematic discourse on humanismnot only in Barry Lyndon, but also in Lolita (1962), Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb (1964), and Eyes Wide Shut (1999)may be his elaboration of a potentially shocking concept: that culture may, in some circumstances, be synonymous with sociopathic violence. In a well-known interview with Michel Ciment, Kubrick made a pointed observation on this subject: Hitler loved good music and many top Nazis were cultured and sophisticated men, but it didnt do them, or anyone else, much good (163). Here Stanley Kubrick echoes the thinking of Walter Benjamin, who wrote in his unfinished

Next page