Be silent in that solitude,

Which is not lonelinessfor then

The spirits of the dead who stood

In life before thee are again

In death around theeand their will

Shall overshadow thee: be still.

EDGAR ALLAN POE,

Spirits of the Dead

This edition first published in hardcover in the United States in 2010 by

The Overlook Press, Peter Mayer Publishers, Inc.

141 Wooster Street

New York, NY 10012

Copyright 2010 by Jeong Hwa (Jid) Lee

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system now known or to be invented, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer who wishes to quote brief passages in connection with a review written for inclusion in a magazine, newspaper, or broadcast.

ISBN 978-1-46830-284-4

To my father

(19201989)

I OWE HEARTFELT THANKS TO JOELLE DELBOURGO, MY AGENT WHO surprised me one day by leaving a voice mail on my phone, and to my editor Juliet Grames, without whom I wouldnt have been able to deliver the content and style that I had tried to create initially. In some places, she virtually wrote for me the expressions I was looking for. Peter Mayer, my publisher at The Overlook Press who rescued To Kill a Tiger from the pile of obscurity, is another person to whom I am indebted. These individuals joined the ranks of the people who live in the most cherished place in my heart, who patiently and graciously nourished me through the most difficult stages of my professional life.

I wish I could describe my gratitude to Sylvie Grignard, my best friend from France who knowsand welcomesthe best and the worst of me. David Walker, too, another friend from the heart of the Southern United States, deserves my sincere acknowledgment. He never tired of listening to me. I have Patrick Enright, a fellow English professor who introduced me to Gustav Mahlers symphonies, and Elvira Casal, a friend in English Department at MTSU, who generously offered her time to advise me on matters of teaching and service. I also have Ellen Jordan, an English faculty at MTSU, who always called me back, and two dear gentlemen named Tom Strawman and Bob Petersen, both professors of English at MTSU, whose constant willingness to listen to my woes was amazing. I have colleagues upon whom I love to unload my anxieties, whose names in alphabetical order appear in the following order: Kirsten Boatwright, Will Brantley, Jimmie Cain, Sandra Cavender, Laura Dubek, Jill Hague, Jan Hayes, Elyce Helford, Allen Hibbard, Kathy Kirkman, Alfred Lutz, Joseph Mitchell, Michael Neth, Sharon Parente, Jan Quarles, Jean Rhodes, John Sanborn, Michael Sniderman, and Steve Walker. Some additional persons, however, must be remembered since they played a critical role in my life in more ways than one: Terry Birdsong, Jimmy Carter, Duane Coon, Sukhee Cho, Michelle Curl, David Curl, Neil Hanson, Felicia Holman, Joy Mitchell, Marnie Mitchell, Michael Ray, and Atsuko Yoda.

I have five women in New York whom I mustnt forget. I am permanently grateful to Carolyn Kim, a former literary agent who, after reading my rough draft twice, brought me the good luck of being introduced to Elisabeth Dyssegaard, the very rigorous, highly skilled editor who helped me to create an entirely new narrative frame. I owe many thanks to Charlotte Sheedy, too, who worked closely with Carolyn Kim and generously gave a chunk of her time to reading my rough draft. Susan Zeckendorf, another literary agent in New York who impressed me with the time-consuming attention she paid to my writing, deserves my gratitude. There is then Carrie Cantor, whose painstaking editorial insights helped me to achieve the level of writing that I possess now.

Finally, I thank my sister In Hwa in Korea, who always and very promptly found the information I needed. I also thank the historian Bruce Cumings for the generous permission to use some of the same terms and vocabulary that he in The Origins of the Korean War created in an attempt to translate the historical events that took place in the Korean Peninsula immediately prior to the Korean War.

W HILE I TRIED TO BE AS ACCURATE AS POSSIBLE IN MY RECOUNTING OF historical events, I added some fiction to the personal lives of the people affected by these events. The names of the characters, too, except those of well-known historical figures, were changed, and some of the facts, including the contents and dates of the incidents in their lives, were altered to accommodate the narrative integrity and consistency. That history is fiction is a clich, and trying to explain why I attempted to fill in the blanks in modern Korean history with the information I gathered on my own would be a waste of time. The truth was intentionally cast out of the official version to be replaced by lies and propaganda, so the only way to arrive at the truth again is an exercise of disciplined imagination, and this I tried to do. I must acknowledge the random power of memory to select what remains in a nations or an individuals psyche, but it is with certainty that I can say that I did my best to take into account the unreliable nature of what I remember.

Since the history of my country has to be thoroughly interpolated into the re-telling of my personal childhood, what I know now must remain entirely mixed with what I remember as my distant past. I must give an adults sharp language to a childs inarticulate thoughts. Since it is equally true, however, that the retrospective reassessments that I gained as a grownup gave me newly born layers of interpretation, it was necessary as well to make them distinct from the narratives regarding my past.

I have now lived in the United States for twenty-eight years, for several years longer than I did in Korea, and I can finally look at the little Korean girl I used to be with a sense of humor. Still, however, unable to abdicate the Korean custom of not calling ones older siblings and parents by their names, I use birth orders and generic nouns to refer to them. Perhaps, I wrote this memoir to let this custom go with laughter.

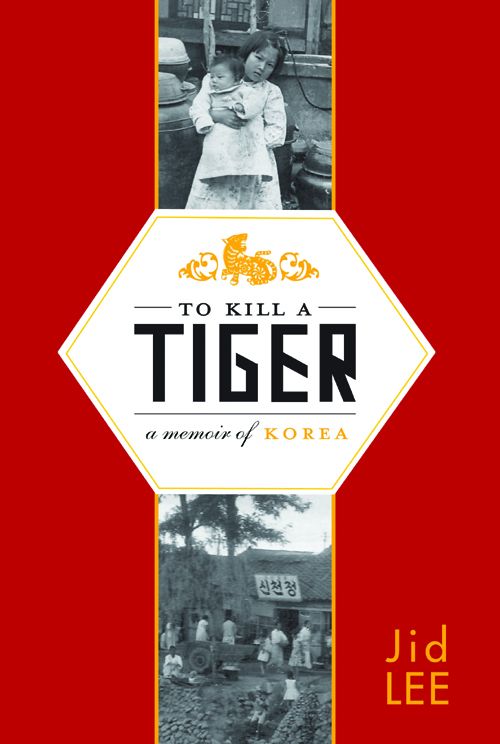

My family in 1956. I am the baby, and that is my mother holding me. Right of her is Father, and in front of him, holding hands, are my two brothers.

M Y NIGHTMAREAND MY DREAMSTARTED WHEN I WAS SIX years old, a child sick in bed.

Your great-great-great-great-great-great-grandmothershe was quite a woman, Grandmother said. She volunteered to be eaten alive by a tiger for her descendants.

I couldnt afford to be bored by the only story Grandmother had to tell me. I had been ill for half a year from renal paralysis, and there was nobody else who could stay by my bedside except the old woman. Mother was busy with housework, Father was at his job, and my brothers and sisters were in school, so Grandmother was stuck with me, and I was stuck with her same old story. With my silence, I invited Grandmother to start from the beginning.

That great-grandmother of yours was always ready to do anythinganythingfor her posterity. She prayed, so that her descendents would prosper forever under the auspices of the gods. And one day suddenly her long-awaited chance came. Grandmother sighed with pride and sadness. Her delivery was always a mix of glee and melancholy, what she actually felt creeping through how she thought she was supposed to feel. When she had just turned twenty, with two sons and one daughter, she had a visitor, a Buddhist monk from a temple in a distant city. He came to tell her that there was a way she could place her children, their children, and these childrens children under the gods eternal good will.