A definitive biography about a significant, but forgotten, figure in American history.

Elegantly written. Vividly reconstructs L'Enfant's life.

Compelling. A well-deserved portrait of an enigmatic historical figure who has long been overlooked.

Berg presents this mixture of biography and urban history with a gusto equal to its subject.

Poignant. Particularly useful in linking L'Enfant's personal struggles to the larger political and constitutional issues to which they were related.

The reader never will be able to walk the streets of Washington again without envisioning the haughty genius of Major L'Enfant looking down from Jenkins Hill [and] in his mind's eye, seeing one of the world's great capital cities spread out before him.

A fascinating story of narrative history.

SCOTT W. BERG

Scott W. Berg holds a B.A. in architecture from the University of Minnesota, an M.A. from Miami University, and an M.F.A. in creative writing from George Mason University, where he now teaches nonfiction writing and literature. He publishes frequently in The Washington Post and lives in Reston, Virginia.

A Note on L'Enfant's English

Whether the young Pierre Charles L'Enfant imagined that America would become his adopted land as he sailed the Atlantic from France during the winter of 1777 is unknown. But soon after his arrival in the New World he did anglicize his name to Peter, and when nearly all of his contemporaries among the French engineer corps returned home, L'Enfant stayed. Later, when offered ten acres of property and the freedom of New York City in return for his services as the architect of Federal Hall, the first home of the new American government under the Constitution, L'Enfant refused the real estate but accepted the honorary citizenship. When his work on the federal city of Washington came to its abrupt end in February 1792 and when, in the early years of the nineteenth century, his professional and financial prospects failed him completely, still L'Enfant stayed.

Despite nearly half a century as an American, L'Enfant never mastered the English language. His surviving letters and other writings, the largest portion of them found in the Digges-L'Enfant-Morgan Papers at the Library of Congress, are serious challenges to accurate transcription. But somehow in nearly every document L'Enfant's meanings and intentions remain clear. His language is full of pride, sensitivity, and determination, which shine through despite his linguistic limitations. The story of Peter Charles L'Enfant is one of genius and failure, of magnificent gestures and miscalculations of all dimensions, and his writings reflect this contradictory nature. When quoting L'Enfant, I have left his prose alone as much as possible, making only small fixes of spelling and mechanics, so that the reader might share in its unvarnished intensity.

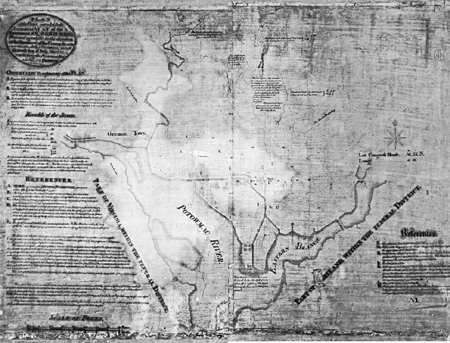

Washington, by George Isham Parkyns, 1795

WEDNESDAY, MARCH 9, 1791

Major L'Enfant entered Georgetown well after dark, nearing the end of one exhausting journey and anxious to begin another. He arrived on foot, blanketed by a steady rain, his breath visible and his overcoat wet, his boots caked with mud, and his belongings packed onto his horse. The stagecoach that had been L'Enfant's southward conveyance had broken down many miles back, but the architect had not waited for another, eager to get to the banks of the Potomac River and begin what promised to be the culminating work of a lifetime.

The major was alone. He was unmarried, without family in the United States, and if there had been any romantic ties in New York City, where he'd lived for most of the past seven years, they had been cut. His father, once an accomplished painter of battle scenes for the court of Louis XV, had died four years earlier. His mother was at home in Paris leading a widow's life in her apartment at the royal tapestry manufacture, sheltered by the king's soldiers from the strikes, protests, and bread riots proliferating elsewhere in the city. The French Revolution was gaining steam, but L'Enfant was not dwelling on the troubles in his homeland. He had already helped to bring about one revolution in America, and that was where his sights and thoughts remained.

The name and talents of Peter Charles L'Enfant were well known to many of America's most influential citizens, and his Federal Hall in New York was the most famous building in the nation. Now he had embarked upon a task that he knew would eventually require the labor of many thousands of men and the outlay of vast sums of money, a task that would also require that he maintain the approbation of the young nation's most eminent leader. Still the major thought of himself as the man who would singlehandedly bring forth an entire city through the force of his own will. For other men it would have been a waking dream, but L'Enfant saw it as his destiny and his due.

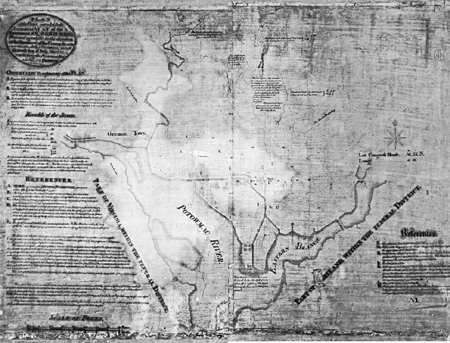

He carried a letter dated the first of March from Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson. Jefferson's instructions, approved by the president, gave L'Enfant the task of surveying the area along the Potomac River between Rock Creek, bordering Georgetown, and the mouth of the Eastern Branch, more than three miles to the southeast, in order that some section of that ground might be transformed into the new and permanent seat of government for the United States. The project was not just ambitious, it was unprecedented: the capital of a new world empire was to be set down in a quiet, sparsely inhabited territory of hills, forests, farms, and wetlands.

This city would not take shape through the slow accretion of time. It would not happen; it would be made. If it were to succeed, L'Enfant believed, it had to be planned by only one man. Though Jefferson's letter did not ask him to create a plan for the capital, L'Enfant had every expectation that his would be the hand holding the pencil, his the mind shaping the streets, squares, and monumental spaces, and his the name most closely associated with its realization. It was a deed in need of a fertile and tireless imagination, and he knew of only two individuals who possessed the necessary breadth of vision and reservoirs of commitment for its accomplishment: himself and the president. He had never failed George Washington in fifteen years of service to the American cause, and he would not do so now.