This Is a Borzoi Book

Published by Alfred A. Knopf

Copyright 2011 by Michael Lindsay-Hogg

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Alfred A. Knopf,

a division of Random House, Inc., New York, and in Canada by

Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto.

www.aaknopf.com

Knopf, Borzoi Books, and the colophon are registered trademarks of Random House, Inc.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Lindsay-Hogg, Michael.

Luck and circumstance : a coming of age in Hollywood, New York, and points beyond / by Michael Lindsay-Hogg. 1st ed.

p. cm.

eISBN: 978-0-307-70149-7

1. Lindsay-Hogg, Michael. 2. Television producers and directorsGreat BritainBiography. 3. Motion picture producers and directorsGreat BritainBiography.

4. Theatrical producers and directorsGreat BritainBiography. I. Title.

PN1992.4.L5355A3 2011

791.430232092dc22

{B} 2011008656

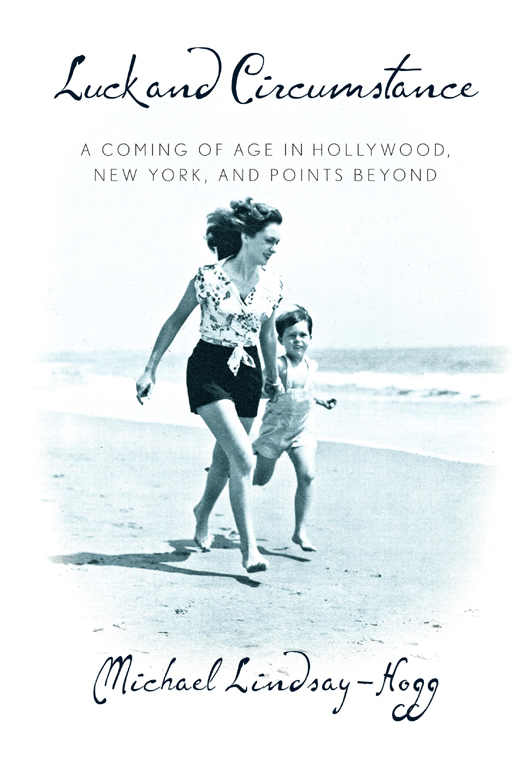

Jacket art: Authors collection

Jacket design by Carol Devine Carson

v3.1

LAT

JMM JM

A L W A Y S

Contents

Illustrations

Edward Lindsay-Hogg, 1941.

Note to my mother from Orson Welles.

With Vladimir Sokoloff, 1943.

My mother and Orson Welles in Heartbreak House, 1938.

With Mary Gillen and my mother.

At age eighteen.

With my dog Freckles, Santa Monica, 1944.

With my mother on the beach, Santa Monica.

My mother and me taken by Robert Capa, 1942. (Robert Capa)

Robert Capa, 1942.

Orson Welles, age eighteen, 1933. (Photofest)

My mother and Edward Lindsay-Hogg, 1939.

Stuart Scheftel interviewing Winston Churchill, 1940.

My drawing of my mother and me at the Waldorf-Astoria. 51 Stuart Scheftel, 1944.

My mother, at the beginning of her British film career.

On the baseball team.

My mother on the cover of Life magazine, 1944. (Photograph by Philippe Halsman, Halsman Archive, Life magazine)

James Brown, RSG! (Photograph by Arnold Schwartzman)

The day we shot Rain, 1966.

John and Mick talking. (Photograph by Ethan Russell)

Eric Clapton, Mitch Mitchell on drums, John Lennon, and Keith Richards. (Photograph by Ethan Russell)

Original Citizen Kane program, 1941.

With Keith, Mick, and behind, our friend Lorne Michaels, whose company had produced the video shoot, 1981.

(Photograph by Arthur Elgort)

During rehearsals for The Normal Heart, Public Theater, 1985.

Photo booth, 1957.

Drawings from my mothers diary, 1943.

A poem by my mother.

Me, age twenty.

Telegram from Orson, 1941.

With my mother, Santa Monica, 1944.

Prologue

A s a small boy, even though my empire existed only in my head, there I was Michael, one name, as a King or a Prince of the realm might be known. Not Mike, not a nickname, but Michael. And I had an army.

I would deploy my toy soldiers in spare regiments, not having that many, and sometimes from a purloined matchbook advertising a restaurant my parents had frequented Id strike a match and, because war has its perils, melt off a lead leg or arm from the little grenadier, once setting alight the field of cotton wool Id laid down to represent the snow on the Russian steppes. Fortunately, Mary was there to help me put it out.

She gave me a slap on my arm and said, Michael, Ive told you never to play with matches.

S o, by what cruel twist of fate had I become Pudge Hoag?

I d been sent to Choate, the boarding school, when I was thirteen, where my last name, Lindsay-Hogg with the hyphen, proved confusing, in some way irksome to the administration, and so, without notice or discussion, it was shortened to Hogg on school lists, for seating in the dining hall or for sports teams, and since most of the probably well-meaning but dense adults thought to pronounce it properly, hog as in pig, would be rude, I became Hoag. I didnt put up any argument, having more pressing crises to deal with on a daily basis. And because the weight Id started to gain when I was eight or so showed no sign of going away, one and then another and another of my school fellows sought to find for me an affectionate nickname. Fatso was first, but then they settled on Pudge. Consequently, during my three years there I felt I was living not as myself but more like an enemy agent with an assumed character and fictitious name, which was fine by me because I knew that as soon as I could, I would find another world to live in. It would have to be better, no matter how rigorous its rules and various its weather.

M y mother, Geraldine Fitzgerald, was an actress and was rehearsing George Bernard Shaws The Doctors Dilemma for an off-Broadway production, playing the wife to Roddy McDowalls tubercular artist. It was December 1954, and I was home on vacation and was by then heavily wrapped in the Pudge Hoag shroud. I was fourteen.

I was standing at the window in my room staring out at a flat sky, when my mother appeared in the doorway wearing her nubbly navy winter coat which stopped just at the knees of her trim legs.

What are you doing today? she asked.

I dont know. Nothing much.

Maybe youd like to come down and watch rehearsal. Ive asked Sidney and he said it would be all right.

I dont know.

Just in case.

She put a piece of paper with the address on my table, written in her large-charactered generous handwriting, and went off to work.

After a couple of hours of aimlessness, sitting in a chair, looking out the window again, arranging my hair in its new style (spit curls modeled on Marlon Brandos Napoleon-hair in the movie Desire), I left the apartment.

One subway and a second and I was outside an old building on Houston Street, at the time a stretch of old buildings in a down-at-heel neighborhood, mostly small stores selling cheap staples with cheap apartments above. But this building had a different role. I took a small elevator up to the first floor, looking at the grimy scissored grille in front of me. The elevator hesitated, then bounced to a stop. I put my hand on the catch and pushed back the stiff old bars. I stepped out.

And my life changed forever.

A slim young man was lying on his front on a wooden bench. One arm was bent and his chin was resting in his hand, and his other hand was on the script he was studying on the floor, a mug of tea beside it.

He turned and looked up at me, took in my age and appearance, and said, You must be Geraldines son, Michael.

Yes, Im Michael.

Come with me, he said, getting up, collecting his script and tea. Ill take you into the theater and well find your mother. Im Roddy McDowall.

He smiled his entrancing smile and we shook hands.

Roddy pushed open a hinged door and we went into the small theater, probably in earlier, pre-television days used by a Yiddish acting troupe. There were some lights focused on the stage and the rest of the theater was in a kind of half light. My mother was at a table onstage, sitting next to another actor, and both were talking to a young man with dark hair and glasses with dark frames who was standing in front of them.

After the conversation, the young man gave them both a hug.