An imprint of Penguin Random House LLC

375 Hudson Street

New York, New York 10014

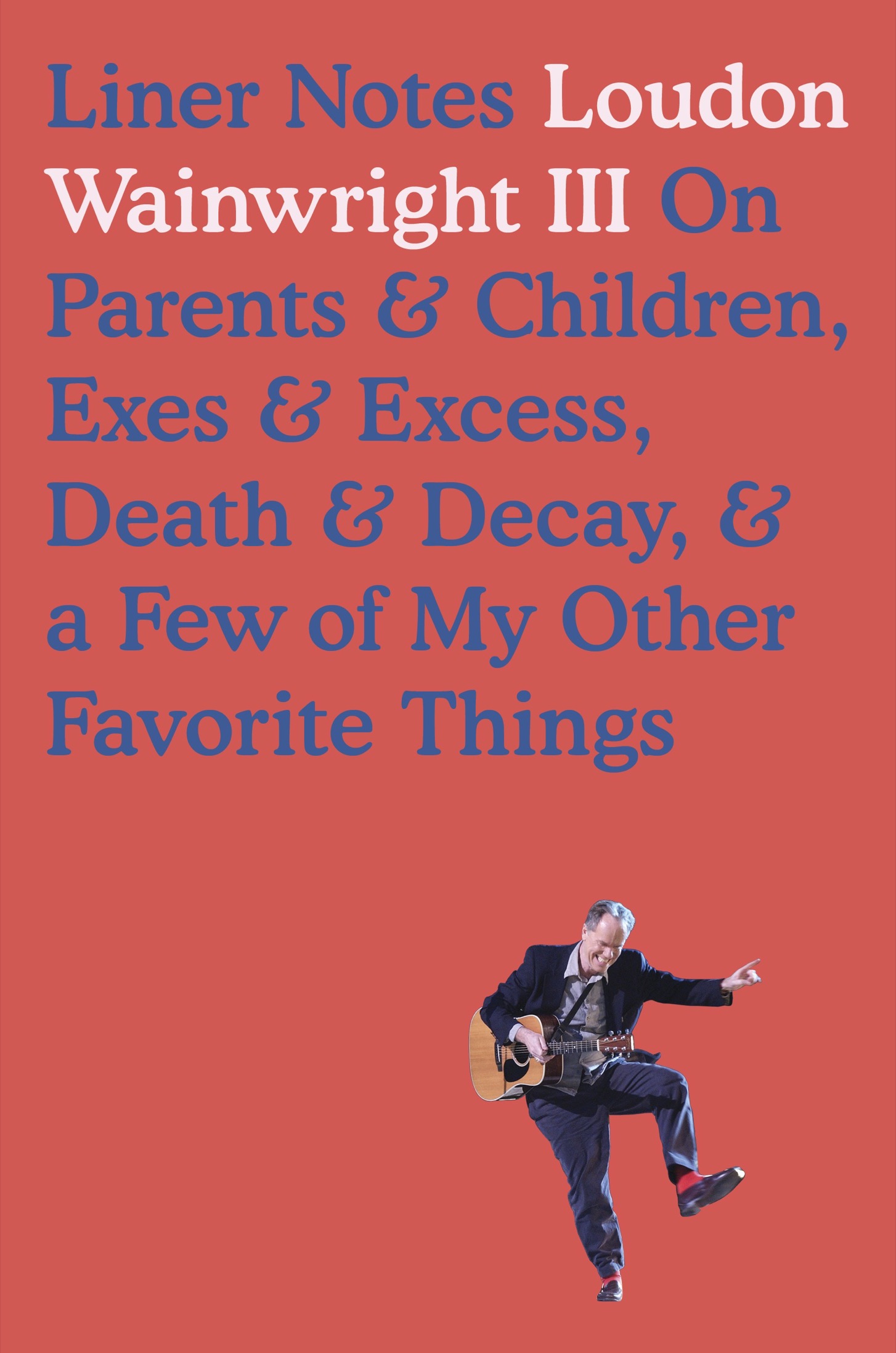

Copyright 2017 by Loudon Wainwright

Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader.

Lyrics are reprinted courtesy of the author and Snowden Music (ASCAP), except for Rowena, courtesy of the author, Dick Connette, and Snowden Music (ASCAP)/Two Fourteen Music (BMI); and School Days, Ode to a Pittsburgh, Four Is a Magic Number, Motel Blues, Red Guitar, and Samson and the Warden, courtesy of MPL Music Publishing.

Blue Rider Press is a registered trademark and its colophon is a trademark of Penguin Random House LLC

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Wainwright, Loudon, III, date.

Title: Liner notes : on parents & children, exes & excess, death & decay, & a few of my other favorite things / Loudon Wainwright III.

Description: New York, New York : Blue Rider Press, 2017.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017020391 (print) | LCCN 2017021211 (ebook) | ISBN 9780698413085 (epub) | ISBN 9780399177026 (hardcover)

Subjects: LCSH: Wainwright, Loudon, III, date. | SingersUnited StatesBiography.

Classification: LCC ML420.W124 (ebook) | LCC ML420.W124 A3 2017 (print) | DDC 782.42164092 [B]dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017020391

p. cm.

Penguin is committed to publishing works of quality and integrity. In that spirit, we are proud to offer this book to our readers; however, the story, the experiences, and the words are the authors alone.

Version_1

For the family, and all we put us through

People will know when they see this show the kind of a guy I am

Theyll understand just what I stand for and what I just cant stand

Theyll perceive what I believe in and what I know is true

And theyll recognize Im a one man guy, always was through and through

Im a one man guy in the morning, Im the same in the afternoon

One man guy when the sun goes down, I whistle me a one man tune

One man guy, one man guy, only kind of guy to be

Im a one man guy, a one man guy... and the one man is me

O NE M AN G UY , 1985

contents

1.

my cool life

O nce upon a time there were songwriters and there were singers. The former wrote for the latter and the labor was usually divided rather than singular. Richard wrote the tune and Oscar wrote the lyrics. George did the music, brother Ira was in charge of the words. There were legendary musical tag teams: Gilbert and Sullivan, Comden and Green, Lerner and Loewe. Occasionally youd get a genius who did it allwords and musiccreative switch-hitters like Frank Loesser and Irving Berlin, but in Tin Pan Alley it was usually a two-person endeavor. And that continued right up into rock and roll. Goffin and King, Leiber and Stoller, Lennon and McCartney (or vice versa, as McCartney would now have it). Of course, Paul and John had themselves in mind as the singers and protagonists of their songs, in the same way that their hero Chuck Berry wrote and sang about his cool life. When John warbled, I once had a girl / Or should I say she once had me, you felt sure that he was the actual guy being had. In traditional folk, blues, and country, few songwriters, if any, could read or write music. They made up songs about what was happening to and around them and then they had the audacity to sing and play the stuff themselves, using guitars, banjos, and harmonicas for self-accompaniment. These were the first singer-songwriters I heard on records, pioneers like Huddie Ledbetter, Robert Johnson, Woody Guthrie, Jimmie Rodgers, and Hank Williams. Guys with guitars telling it like it was. The it in question was the life they led. They spilled the beans and gave up the gory details. As a listener you felt you were getting something at its source, something simple, direct, and easy to identify with, because it turned out that their beans were not unlike your own. Everybody has pretty much the same gory details, which is why autobiography, and art, for that matter, work.

When I saw Bob Dylan at the Newport Folk Festival in 1963, there was a whole lotta identification going on. Here was a guy just a few years older than I was, writing and singing about what was happening in the worldhis world and mine. These were the heady days of Blowin in the Wind and The Times They Are A-Changin, when there were social issues to sing about and apostrophes in song titles. The not-so-nice Jewish boy from Hibbing, Minnesota, sounded like a sixty-year-old black bluesman whod listened to a ton of Woody Guthrie, but Bob was young and just searching for himself. On his first recordings, Ray Charles all but impersonates his hero Nat King Cole. By the time Dylan went and, for that matter, became electric two years later at Newport, hed become a fully formed original whod left his contemporaries and his own influences in the dust. After 1965, Bob seemed to be pretty much focused on his cool, albeit rather cryptic, life. It had gone from Hattie Carroll was a maid of the kitchen to You got a lotta nerve / To say you are my friend, which for my money is going from good to even better.

So whats the big rule/clich when it comes to writing? Write about what you know? When I started writing songs in 1968 I didnt know about much. Raised in an affluent suburb of New York City, Id gone to a boys boarding school, dropped out of college, been busted for pot, and had survived a few disastrous puppy-love affairs. Id mowed some lawns and had hitchhiked to New Canaan, Connecticut, but I hadnt harvested a single bale of cotton or ridden any rails. Still, I somehow managed to write two or three songs per week, drawn from my pathetic dearth of experience. Like most serious, young, egotistical artists, I thought my life, though yet to be cool, was nonetheless interesting. At least I was smart enough to know I had to make it seem interesting. So I put some work into presentation. To separate myself from the pack of bell-bottomed, ponytailed, guitar-toting song-slingers, I wore khakis and Brooks Brothers shirts and kept my hair unfashionably short. To cope with coffeehouse stage fright, while performing I physicalized my fear into strange, jerky body gyrations, replete with leg lifts, facial grimaces, and lots of tongue wagging. I was trying to make sure people noticed me and, within a year, Atlantic Records did. I made my first two albums for them. The records were positively retro, unadorned, without a trace of the drums, bass, and tasteful pedal-steel-guitar lickage that was going around at the time. My instincts paid off, at least for the critics, who were always looking for the next new thing and desperate to fill the Dylan vacuum (Bob was out of commission at that time, holed up in Woodstock, recovering from a motorcycle accident). I was, to shamelessly quote one hyperbolic journalist, a blinding new talent. All my work on packaging had paid off. Id been noticed. The songs I had written were also good. That helped. Once I began in earnest, I also decided to stop listening to the competition. I didnt want to check out this new guy David Bowie or hear what Dylans latest was. I put an embargo on any and all incoming influences, because I sensed it was important to be original, to not be like anyone else. If I was in a car and another singer-songwriter came on the radio, Id turn it off or go looking for the jazz station. People always want to know what I listen to. My answer to that question has been and continues to be Dead black piano players.