It seems remarkable now, when new authors can reasonably expect early induction into the heady world of literary festivals, the media and the writers community, that I did not meet Margaret Mahy for five years after my debut novel was published. Another two years went by before I heard her give a major speech.

There were several reasons for this long wait. The early 1980s had yet to see the spread of the literary festivals Dunedin, Wellington, Auckland, Christchurch, Whakatane, Waitakere, Bay of Islands now securely established on the New Zealand arts calendar and providing, among other things, invaluable opportunities for writers to meet their colleagues. Then, a writer might be individually invited to a more specialised, professional occasion, say, a library conference, a childrens literature or literacy event, a university seminar or a schools book week. If shortlisted for an award, you might briefly meet other authors, under less than relaxed conditions, at prize-giving ceremonies.

Then surely I, and other up-and-coming writers of the 1980s, would have met one of New Zealands all-time greatest writers, twice winner (in 1982 and 1984) of Britains Carnegie Medal, at these occasions, adding New Zealand awards to those she was collecting overseas? No, because her novels, short story collections and picture books, being published principally in England and America, were not then eligible for most New Zealand awards. With the exception of the Esther Glen Medal, which she won six times from 1970, you do not see most of her great novels of the past 20 years included in New Zealands book awards.

To me, as a parent, a newish writer and an eager reader of every Margaret Mahy novel as it appeared, the author down in Governors Bay on the shores of Lyttelton Harbour was a distant and Olympian figure.

I finally met her in August 1987, at a screenwriting course being run in Wellington. My novel Alex, due for publication in September, was also being adapted for television, so the five trips to Wellington seemed a worthwhile investment in my role as script consultant and coincidentally the opportunity to meet at long last the author I admired above all others. Margaret, by then also recognised as an innovative and successful writer of childrens television, with Cuckooland and Strangers under her belt, was to conduct the last session.

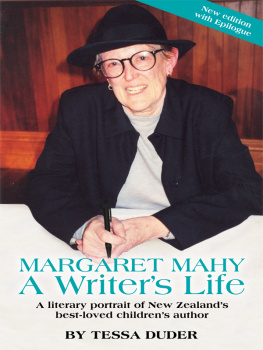

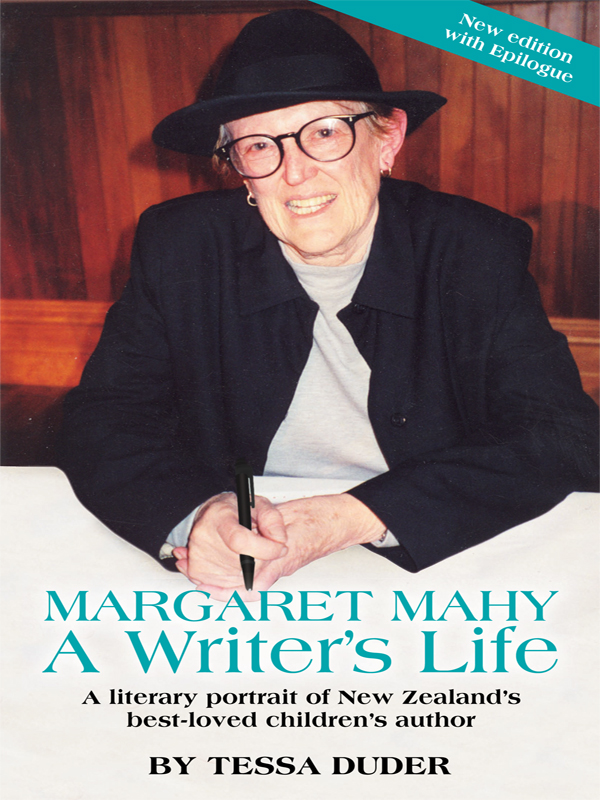

Oh, Tessa, Im so pleased to meet you, she said in that unmistakeable New Zealand small-town voice, a broad smile under the soft felt Homburg-style hat she often wore in public to cover fine and anxious hair. Holding out mint copies of my first two novels, Night Race to Kawau and Jellybean , she added, to my astonishment, Here, Id be so pleased if youd sign your books for me.

I later heard that other new writers had similar experiences of this simple, generous gesture of support for the genre and the writers behind the books. In recent years she often lamented that she simply couldnt keep up with all the childrens books local and otherwise that she wanted to read, never mind the adult ones; for decades Margaret had followed her librarians commitment of reading virtually every New Zealand childrens and young adult novel published. She happily bought literally hundreds of them, creating on her living rooms high-reaching bookshelves what must have been one of the best private collections of New Zealand childrens books anywhere in the country.

I remember her session for one other reason. Until then, a good deal of the discussion had been of a defensive nature: how to prevent or at least deflect nasty producers, directors, financiers, script editors and even uppity actors from generally conspiring to ruin your carefully polished script. In the space of a few minutes, Margaret changed all that. Not for her the inevitability of the beleaguered writer, knowing the risk of being called precious but standing firm against the suits and barbarians. Writing for television, she stated then and continued to say throughout her life, was teamwork with other clever, talented people, and for novelists who normally work in solitude, it was entertaining, surprising, intense, stimulating, full of excitement and thoroughly enjoyable . Her session, an informal talk with 12 or so students in a small room, was positive, wise, often very funny, slyly self-mocking, discursive to the point of seeming to tilt the topic off-balance into a lengthy ramble, but also, given a few minutes of often virtuoso deviation, bringing her point unfailingly, triumphantly home.

It was Margarets brilliance as an essayist and speech-writer, her supreme versatility and completeness as a writer, along with my belief that as a novelist she was (in her own country) shamefully neglected, that largely led me to this book. Even that experience in Wellington was hardly sufficient preparation for the first few occasions I heard her delivering a formal speech to a large and well-informed audience. The first was two years later in New Orleans, where she was a keynote speaker at the American convention of the International Reading Association, which, thanks to an Arts Council grant, I was attending on my way to Rome to research the third book in the Alex quartet.

In New Orleans, I sat spellbound and proud among a large gathering of equally captivated Americans as, for over an hour, Margaret brought all her wit and eloquence to bear on the subtle, scholarly, subversive nature of her ideas. In 1990, it was Rotorua, a full hall of teachers at the South Pacific Convention of the International Reading Association listening to her talk on censorship in childrens literature, and also in Wellington, at the International Festival of the Arts Readers and Writers Week, where I found myself sharing a platform for a childrens session with Margaret Mahy and the acclaimed British poet Charles Causley. Though comparatively little published as a poet, she was as learned and compelling in the specialist field of childrens poetry as he, and able to quote with ease from his widely known, infinitely sad pieces My Mother Saw a Dancing Bear and Timothy Winters, among much else. Causley was gratified, respectful, even overawed.

On these and other occasions through the 1990s, the Mahy hallmarks, well honed in more than a decade of constant public speaking, were always there: the rich, magical language; the sheer musicality and rhythmic ease of her prose; the provocative and often contrary ideas; the incursions into philosophy and science, architecture and the arts, history and anthropology; the literary quotes and allusions; and the social commentary and the psychological insight. Few academics could match her knowledge of childrens and adult literature, both historical and contemporary. Along with a lifetime of reading, many years as a professional librarian, and, by her death, 30 years as a full-time professional writer, there was a phenomenal memory which enabled her, in any question time or informal gathering, to offer impromptu musings on practically any childrens or young adult book you care to name. Characters, storyline, issues, the authors place in the genre under discussion, all were effortlessly, accurately recalled and shared. The same largely applied to adult classic and contemporary fiction or works on a range of science topics, philosophy, popular culture, plays, poetry, horror stories, ghost stories.

In private, she was a creative listener as well as an enthusiastic talker and participant in lively debate. The extent of her reading often astonished: David Hill, writer and passionate amateur astronomer, once settled down to instruct her on the matter of black holes. Two minutes later, he recalled, the reverse was happening with absolutely no arrogance she just paid you the tribute of assuming you could participate. No matter how tired or jet-lagged she was, how currently immersed in work or family affairs, her presentations were invariably delivered with energy, good humour, respect for her audience and skilful timing in a New Zealand accent that she once said sounded more like the sort of voice that should be reading out cake recipes over the radio.