Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader.

DUTTON is a registered trademark and the D colophon is a trademark of Penguin Random House LLC.

has been applied for.

While the author has made every effort to provide accurate telephone numbers, Internet addresses, and other contact information at the time of publication, neither the publisher nor the author assumes any responsibility for errors or for changes that occur after publication. Further, the publisher does not have any control over and does not assume any responsibility for author or third-party websites or their content.

Penguin is committed to publishing works of quality and integrity. In that spirit, we are proud to offer this book to our readers; however, the story, the experiences, and the words are the authors alone.

Some names and identifying characteristics have been changed to protect the individuals involved.

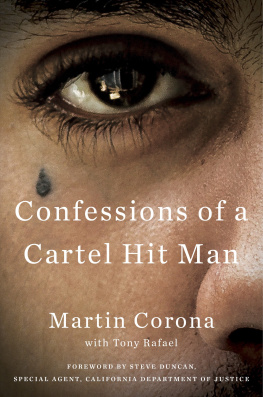

Foreword

Steve Duncan, Special Agent, California Department of Justice

We got a multiple murderer, a brutal hit man who participated in many killings and murdered at least eight people himself. He had often left victims near death. He had destroyed families in the United States and Mexico. We got him. Martin Corona, an accomplished hit man for the extremely violent Tijuana Cartel, also known as the Arellano Flix Organization, signed a plea agreement created by the prosecutor and me. Corona then stood before a federal judge and pled guilty to cocaine distribution. He was sentenced to roughly twenty-five years.

Wait! He pled to cocaine distribution when he was a multiple murderer and youre good with this? Hold on now, theres more.

Corona was thirty-seven years of age. In the federal system, you do eighty-five percent of your sentence. In his case, 20.6 years. Corona would be released when he was fifty-eight years old. Corona was sentenced in October 2001 and would not be released until 2022.

During intensive debriefings with Corona in 2001, he confided to our team that he had hepatitis C, a virus that is chronic and can lead to an early death. We feigned sympathy, but after we locked Corona back into his cell, we smiled. We truly believed he would die in prison. Divine intervention, I thought.

Let me get to the facts.

It was September 1999 and my cell phone rang. As I answered, Bill Ziegler, a parole agent, cut me off and said, Get your ass down here right now. He explained that Martin Corona was in a vulnerable situation and it might be the time to break him. Zieglers office was in Oceanside, about a forty-five-minute drive from San Diego. I put down everything, grabbed my partner, California Department of Justice special agent Javier Salaiz, and we headed north.

From 1992 to 1996, I was a member of the Violent Crimes Task ForceGang Group comprised of the Drug Enforcement Administration, Federal Bureau of Investigation, San Diego Police Department, San Diego County Sheriffs Department, US Marshals Service, San Diego County Probation Department, US Attorneys Office, the District Attorneys Office, the Immigration and Naturalization Service, and the California Department of Justice. I was deputized by the Drug Enforcement Administration to enforce the federal drug laws, or Title 21 of the United States Code. At the time, I was investigating members of the Logan Heights street gang and other Hispanic gangs working as assassins for the Tijuana Cartel.

On May 24, 1993, at the Guadalajara International Airport in Jalisco, Mexico, Cardinal Juan Jesus Posadas Ocampo was shot and killed by enforcers for the Tijuana Cartel. It was a case of mistaken identity, as the enforcers believed that their drug rival, Joaquin Chapo Guzman Loera, was in the white Grand Marquis that the cardinal was being escorted in. About a dozen of the enforcers present were Logan Heights gang members. The Arellano Flix brothers, who headed the cartel, instantly became some of the worlds most wanted criminals, and Mexico wanted justice. Many of the enforcers were rounded up in the US and Mexico and sent to Mexican prisons to face charges related to the cardinals murder. In those days in Mexico, their system was described as Napoleonic and suspects were guilty until proven innocent.

In 1995, the Arellano Flix Organization Task Force was created to target and dismantle the Tijuana Cartel. DEA agent Jack Robertson was the case agent of the Tijuana Cartel and he led the charge at the AFO Task Force. Jack had recruited me to assist in his investigation in 1993.

The government of Mexico eventually dropped the charges on many of the gang members involved in the murder of the cardinal. So much for Napoleon. As the enforcers were released, many returned to San Diego and other parts of the US. An angry US Attorney, Alan Bersin, tasked one of his federal prosecutors to lead the prosecution against the enforcers in the Southern District of California. I was assigned as the case agent. We developed a federal Drug Kingpin case against David Barron, Corona, and ten enforcers and secretly indicted them in June 1997.

Barron, a Logan Heights gang member and Mexican Mafia prison gang member, had become a top enforcer for the Tijuana Cartel after his heroics at Christines disco in Puerto Vallarta in November 1992. As an escort for the cartels top brass, he got them safely out of the disco as Chapos troops attempted to ambush and kill them. After the dust settled, Benjamin Arellano Flix, the cartels leader, personally assigned him to head the cartels enforcement arm, and Barron began to recruit his fellow gang members from San Diego. Barron was a one percenter, a term we use in law enforcement for the gang leaders. Barron, like other one percenters, was charismatic, aggressive, and ambitious.

In November 1997, Barron was killed while he ambushed and shot a Tijuana newspaper editor. We unsealed the indictment and arrested several of the enforcers who were in the US. With the long sentences each was exposed to, we received their cooperation, and the prosecutor and agents were soon able to debrief several defendants who pled guilty for their parts in the murder of the cardinal. Every defendant mentioned Corona as a member of the Death Squad, a special group of cartel enforcers with tactical ability. They had all witnessed Corona being paid $15,000 to $25,000 for murders. Corona was put at the top of the list for the second round of indictments.

So a year or so later, Javier and I went into an interview room, where I met Corona for the first time. I was direct. I told him that I was preparing to indict him and that I knew he was a high-level enforcer for the Tijuana Cartel. Corona did not mention any violence but did admit guarding stash houses for the cartel. We also spoke about family, fishing, and the beauty of the Sierra Nevada mountains, for which we shared a fondness. After a couple hours of conversation, I told him he had a decision to make: Cooperate with the government or go to jail for the rest of your life. He responded that the statute of limitations was up for his drug activity and he no longer worked for the cartel. I told him there was no statute of limitations for murder.