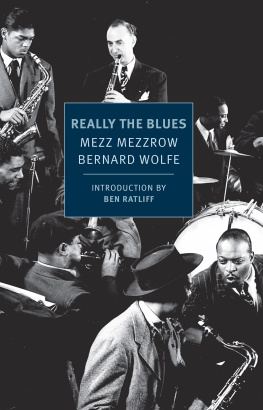

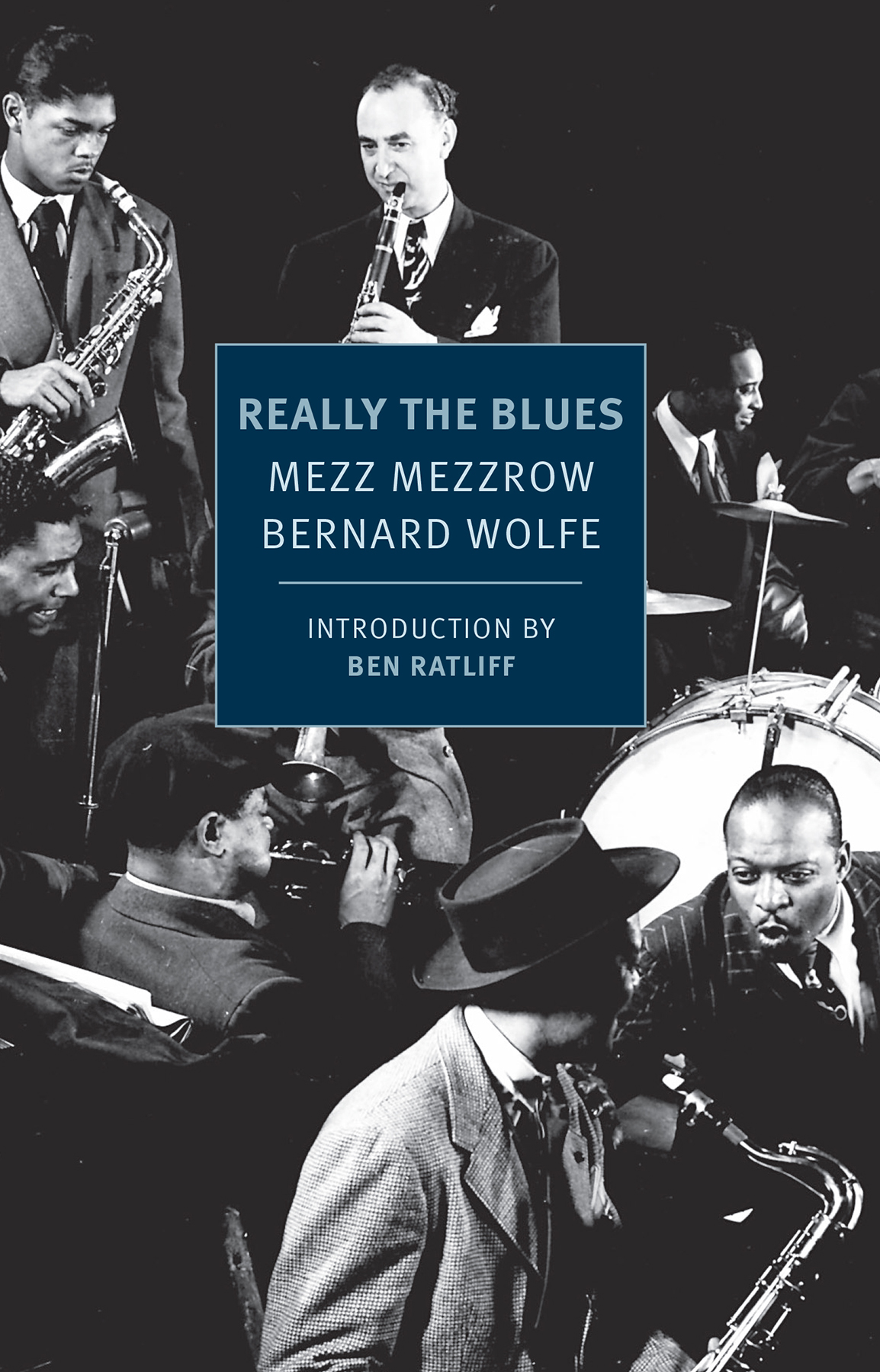

MEZZ MEZZROW (18991972) was born Milton Mesirow in Chicago to a Jewish family as respectable as Sunday morning. As a teenager, however, he was sent to Pontiac Reformatory for stealing a car; there he learned to play the saxophone and decided to devote his life to the blues. Beginning in the 1920s, he had an intermittent career as a sideman in jazz groups, and struck up friendships with many of the greats of the day, including Louis Armstrong and Bix Beiderbecke. Enamored of African American culture, he helped channel it to whiter and wider audiences, backing and producing significant recordings by Frankie Newton, Teddy Wilson, Sidney Bechet, and Tommy Ladnier, among others, and helping to spark the New Orleans revival of the late 1930s. In the 1940s, Mezzrow started his own record label, King Jazz Records. He spent the last years of his life in Paris.

BERNARD WOLFE (19151985) was born in New Haven and attended Yale University, where he studied psychology. An active member of the labor movement, he moved to Mexico for eight months in 1937 to work as personal secretary and assistant to Leon Trotsky. In subsequent years, Wolfe held disparate jobsfrom serving in the Merchant Marines to working as a pornographic novelist to editing Mechanix Illustratedwhile writing fiction and science fiction. His best-known work is the 1959 novel The Great Prince Died, a fictional account of Trotskys assassination. Among his other books are The Late Risers, In Deep, Limbo, and Logans Gone.

BEN RATLIFF has been a jazz and pop critic for The New York Times since 1996 and has written four books including The Jazz Ear: Conversations over Music and Coltrane: The Story of a Sound. His latest book is Every Song Ever: Twenty Ways to Listen in an Age of Musical Plenty.

REALLY THE BLUES

MEZZ MEZZROW

and BERNARD WOLFE

Introduction by

BEN RATLIFF

NEW YORK REVIEW BOOKS

New York

THIS IS A NEW YORK REVIEW BOOK

PUBLISHED BY THE NEW YORK REVIEW OF BOOKS

435 Hudson Street, New York, NY 10014

www.nyrb.com

Copyright 1946 by Mezz Mezzrow and Bernard Wolfe, copyrights renewed 1974

Introduction copyright 2016 by Ben Ratliff

All rights reserved.

Cover image: Gjon Mili, Jam Session, 1943; top: Mezz Mezzrow, bottom, left to right: Dizzie Gillespie, Lester Young, Count Basie (all others unidentified); The LIFE Picture Collection/Getty Images

Cover design: Katy Homans

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Mezzrow, Mezz, 18991972, author. | Wolfe, Bernard, 19151985, author. | Ratliff, Ben, writer of supplementary textual content.

Title: Really the blues/by Mezz Mezzrow and Bernard Wolfe; introduction by Ben Ratliff.

Description: New York: New York Review Books, 2016. | Series: New York Review Books classics | Reprint. Originally published: New York: Random House, 1946. | Includes index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2015037760 (print) | LCCN 2015039294 (ebook) | ISBN 9781590179451 (alk. paper) | ISBN 9781590179468 (epub)

Subjects: LCSH: Mezzrow, Mezz, 18991972. | Jazz musiciansUnited StatesBiography.

Classification: LCC ML419.M5 A3 2016 (print) | LCC ML419.M5 (ebook) | DDC

788.6/21643092dc23

LC record available at http://lccn.loc.gov/2015037760

ISBN 978-1-59017-946-8

v1.0

For a complete list of titles, visit www.nyrb.com or write to: Catalog Requests, NYRB, 435 Hudson Street, New York, NY 10014

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

O N N EW Y EARS D AY OF 1947, NOT LONG AFTER R ANDOM House published Mezz Mezzrows memoir, Really the Blues, there took place at Town Hall a kind of musical-revue version of his life. Mr. Mezzrow himself served as the narrator, reported The New York Times the following day. He told how he had encountered different jazz players in different places. Then the curtains opened and instrumentalists or singers acted the parts of the performers mentioned, performing in the styles of the originals.

Mezzrow was an early traditionalist: His love for jazz centered on New Orleansderived music and swing, and stopped before bebop, then a current language. He was a white jazz musician who played on some excellent records (including some sessions organized in late 1938 and early 1939 by the jazz critic Hugues Panassi, led variously by Mezzrow or the trumpeters Tommy Ladnier and Frankie Newton, and described in this books ); had a rigorous and principled feeling for the blues; followed a lifelong yearning to be a musician, a Negro musician, hipping the world about the blues the way only Negroes canyet was generally overshadowed, talent-wise, by his peers.

At Town Hall, the pianist Sammy Price played the role of Tony Jackson, who shows up early in the book. Jackson was a New Orleansborn musician who moved to Chicago, Mezzrows town, and died not long after the teenage Mezzrow saw him play at the Pekin Inn; he never recorded. And so Mezzrows eyewitness account of him, however stylized, remains valuable. (The passage uses its jive mode to identify Jackson as one of the greatest blues piano players that ever pounded a joybox, and its psycho-moralizing mode to hear in Jacksons songs the Negros real artistry with his prose, and the clean way he looks at sex, while all the white songs that ever came out of whorehouses dont have anything but a vulgar slant and an obscene idiom.) The singer Coot Grant played the role of Bessie Smith, whom Mezzrow admired greatly. A young sextet, including Bob Wilber and Dick Wellstood, performed as the Scarsdale High School Gangreferring to the group of young white Chicago musicians in the 1920s known as the Austin High School Gang, to which the slightly older Mezzrow had a bootleg-liquor-sharing and semi-mentoring relationship. Sidney Bechet played Sidney Bechet. Mezzrow played docent, but certainly not star soloist: The Times writer didnt weigh in on his talent, and only noted that he joined some of the sessions as a clarinetist.

Throughout the program Mr. Mezzrow kept insisting that the performances were authentic jazz, the Times writer reported. Other jazz notables, he implied, had gone to the other side. Mezzrow knew about going to the other side, in another sense. Was there a wink there? Was the whole thing a giant wink?

In Really the Blues, Mezzrow draws a circle around the idea of the real, but as he does so he stands outside of the circle, looking in. Mezzrow was conveying to the Town Hall audience that Bechet was a walking principle of authenticity, and that his own career had been all about staying close to such principles. He understood real jazz as fairly serious and simple, and as Southern black expressionnot to be confused with modern and East Coast tendencies, which he mostly saw as corruptive. (Type the words real and modern into a search engine for this book, and you will find an X-ray image of Mezzrows tastesshaped and limited, surely, by a mixture of what he had witnessed, what he was technically capable of playing, and how he might have felt his livelihood and identity threatened.)

Mezzrow was a scold with his feet slightly off the ground, someone who could transmit real awe and inspiration about the music he lovedwho could explain why jazz is not just an arrangement of notes but a way of looking at the worldbut who also liked to remind his juniors that they probably didnt know what real music was. He often sounded something like a critic, and the opinions of critics mattered to Mezzrow at the time of this book: particularly those of Panassi and Ernest Borneman, both of whom gave him powerful votes of confidence. One imagines he would not have been pleased by the judgment of Nat Hentoff, who described him in 1953 as so consistently out of tune that he may have invented a new scale system, or Whitney Balliett, who in 1977 called him abysmal, or Gunther Schuller, who in 1989 called him inept. (The tides may yet turn the other way. In his 1997 book