CONTENTS

1 IN THE BEGINNING

Women Warriors of Myth and Early History

2 THE CAPTAINS AND THE QUEENS

Women Leaders and Commanders, Directing War and Conflict

3 RUNAWAYS AND ROARING GIRLS

Mavericks, Misfits, Malcontents, and Wild Ones: Women Seizing the Chance of War to Live and Fight as Men

4 REBELS AND REVOLUTIONARIES

Women Taking Up Arms for a Cause

5 CREATURE COMFORTS

Courtesans, Consorts, and Camp Followers: Women Drawn into War to Minister to Men

6 INTO UNIFORM

Women Mobilized to Support the War Effort

7 AT THE SHARP END

Modern Soldiers, Sailors, and Airwomen

8 HEALING HANDS

Doctors, Nurses, Medics, and Health Workers

9 RECORDING ANGELS

Singers, Entertainers, Artists, Propagandists, and Chroniclers of War, the Good and the Bad

10 VALKYRIES, FURIES, AND FIENDS

Ruthless Opportunists, Sadists, and Psychopaths Unleashed and Empowered by War

11 ARMIES OF THE SHADOWS

Spies, Agents, and Underground Workers

This book is for our mothers,

Lucy Simpson and Betty Cross,

who lived through two world wars

Let the generations know that women in uniform also guaranteed their freedom.

Mary Edwards Walker, Civil War doctor and only female holder of the Congressional Medal of Honor

INTRODUCTION

T HEY FOUGHT LIKE DEVILS, far better than the men.

So Georges Clemenceau, then mayor of Montmartre, recalled the women of the Paris Commune who manned the barricades at Frances republican uprising of 1871. Fighting to the last under a relentless bombardment as government troops stormed the city with a loss of 25,000 lives, they died like men, too. As Clemenceau somberly testified, I had the pain of seeing fifty of them shot down, even when they had been surrounded by troops and disarmed.

History has seen many such acts of courage, daring, and self-sacrifice by women like these. These traits are to be found today, in the opening years of the twenty-first century, in such women as former US Army helicopter pilot Major Tammy Duckworth (see Chapter 7), who lost both her legs when her Black Hawk was shot down in Iraq in 2004; and Colonel Martha McSally (see Chapter 7), who flew A-10 ground-attack missions in Afghanistan and in 2004 became the first woman to command a United States Air Force combat squadron.

No comprehensive record exists of the many roles played by women in the countless wars, both hot and cold, that have marked human history. This book is written to bridge the gap in the way we look at history, women, and war, pulling together in a single volume the many strands of this continuing historical drama. Women have taken a vital part in ancient and medieval warfare; in the world wars of the twentieth century; in armed insurrections; in religious, ethnic, and tribal conflicts; and in the Cold War that lasted from 1945 to the early 1990s.

Today they are caught up in the so-called clash of civilizations between Islam and the West and in the violent politics of the Middle East and Africa. In the modern, mixed-gender armed forces deployed in these trouble spots, often under the banner of the United Nations (UN) or the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) (see Chapter 6), women play increasingly significant and sometimes controversial roles both in making war and in keeping the peace.

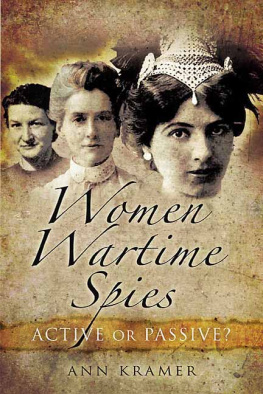

Naturally, women have not always served on the side of right. No account of women and war can be complete without coverage of its dark side, like the part played in the death camps of World War II by the women of the SS, or the career of Saddam Husseins biological warfare expert, Dr. Huda Salih Mahdi Ammash (see Chapter 10), infamous as Dr. Germ. Nor can we overlook the intelligence careers of master spies such as Ruth Werner (see Chapter 11), or the grim exploits in the more recent past of female Tamil Tigers (see Chapter 4), or Palestinian Suicide Bombers (see Chapter 10). These pages contain characters as diverse and complex as General Harriet Tubman (see Chapter 4), the former slave who became the only woman to command a military mission in the American Civil War; Margaret Thatcher (see Chapter 2), a modern Boudicca (see Chapter 1); and the Cuban revolutionary and cultural tsar Hayde Santamara (see Chapter 4).

This rich history is crammed with other characters and events crying out for a wider audience. Readers will find here most of the names they know, or think they know: Boudicca, Joan of Arc (see Chapter 3), Elizabeth I (see Chapter 2), Florence Nightingale (see Chapter 8), and Golda Meir (see Chapter 2). But they appear here as they have not always done in the past. Florence Nightingale, for instance, was not known to the troops in the Crimea as the Lady with the Lamp, an invention of the war correspondent of The Times of London, but as the Lady with the Hammer. This nickname arose from one of her fearless exploits, when she defied a military commander to smash her way into a locked storeroom and released much-needed medical supplies, to the great delight of the wounded men.

Like Nightingales story, most accounts of women at war offer an unsatisfying and often mythologized pop-up history of a few outstandingly courageous and sometimes eccentric women, which invites the reader to do little more than mutter, What a gal! So the courage in World War II of the British agent Odette Hallowes (see Chapter 11) is solemnly celebrated, but not the complaint by her French Resistance colleagues that she spent too much of her time in bed with fellow agent Peter Churchill.

And these women did not operate alone. The story of Hallowes and other British women agents can only be understood in the context of the Special Operations Executive (SOE, see Chapter 11), which directed their work. Many fascinating questions about women at war are raised by considering the aims and methods of the SOE, its policy on the recruitment of women, and the legal problems this brought in its train. The same is also true for the American equivalent of the SOE, the Office of Strategic Services (OSS, see Chapter 11).

In Hell Hath No Fury, these womenboth the good and the badrub shoulders with one another, and challenge conventional notions of womanhood. Yet many of their stories are not widely known and have not been incorporated into an overview of womens experience and achievement in thousands of years of warfare. Encyclopedias or general accounts of war give little or no attention to the contribution of women, and the fair sex finds itself consistently written out of the records. Female war leaders of the past regularly found their victories attributed to their generals, while some women were not acknowledged at all: the Muslim chroniclers of Africa, a continent whose tradition of warrior queens reaches back into prehistory, regularly omitted queens regnant from their lists of rulers, because women holding power did not accord with their theology of Islam.

As this suggests, the careful massaging of the record to ignore or minimize the contribution of women is as old as history itself. Resisting the Roman invasion of Britain while contending with the infighting of rival Celts, the first-century British queen Cartimandua (see Chapter 1) displayed outstanding qualities as a war leader, defending her considerable territories for many years. But her success has proved far less interesting to historians than the spectacular downfall of her contemporary, the warrior queen Boudicca, who serves as an Awful Warning to women not to embark on the path of war. When Cartimanduas career is discussed, her marital status and her sex life receive greater coverage than her military prowess, just as any tabloid newspaper would treat her today.

Next page