Prologue

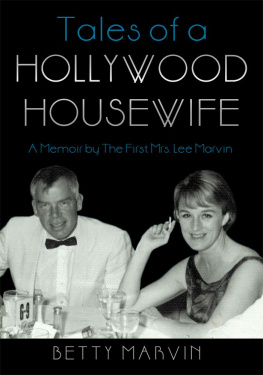

T HE TOTAL QUIET OF AN AFFLUENT NEIGHBORHOOD IN THE stillness of a Sunday morning in early November enveloped Cypress Avenue, a block-long street just above the northwest hook of San Diegos Balboa Park. Suddenly, five gunshots ripped through the silence. Those five reports marked the violent end to one of the bitterest divorces in the towns recent memory and the start of an even more notorious criminal case.

The savagery that shattered the early morning quiet had been predicted by several people, including those most nearly involved, but no one had really believed it would happen. The gunshots were the final eruption of long-simmering rage and humiliation, fueled by fears, some real and some imagined, and a sense of desperation.

Some people said later the shooting was a vicious, premeditated act; others argued it was provoked, the result of a malicious campaign to undermine and discredit a woman who had been grievously wounded. Its outcome left two people dead, four children orphaned, and a town divided.

A BOUT FIVE A.M. ON NOVEMBER 5, 1989, A WHITE CHEVROLET Suburban van turned onto the empty street and stopped at the two-story brick house near the end of Cypress Avenue. The curved driveway passed in front of the four white columns that rose to the overhanging roof; the two in the center framed the pediment-topped front door. White shutters decorated the second-story windows, and two wings covered in white clapboard grew from the central structure. The Georgian-style mansion seemed out of place next to the more traditionally California outlines of its tile-roofed neighbors in the tiny enclave of wealth known as Marston Hills.

But that seemed to be the point for the houses owner, Daniel T. Broderick III, a medical malpractice attorney and a major figure in San Diego legal circles. A dashing dresser who wore only custom-tailored suits and had a top hat and cape for more formal occasions, he identified with the mansions Southern plantation aura of red brick, double chimneys, and columns. The big house represented success to Broderick, at least as he had defined it years earliermansions, cars, and boatsto his first wife.

Elisabeth Anne Broderick, known as Betty to her friends, emerged from the Suburban dressed in casual clothes and a diamond necklace and earrings. She walked to the front door. A tall, slightly overweight woman with a puffy face, she wore her blond hair pulled back into a ponytail. She peered through the doors glass side panels to the dark interior. She looked like a suburban matron, but her stealthy movements were those of a burglar, checking for signs of life inside the big house.

She clutched an almost comically large key in one hand and tried it in the lock. Her other hand hung down by her side, as if she were gripping something heavy. When the door wouldnt open, Betty turned to the back of the house. The back door was more cooperative, and she entered quietly. She was inside without a sound to break the stillness.

Upstairs in the master bedroom above the front door, no sense of impending violence disturbed the sleep of Dan Broderick and his bride of seven months, Linda Kolkena Broderick. They had spent Saturday on the water with friends, on Dans powerboat. Fresh air and salt spray are terrific soporifics. He wore only undershorts in the cool San Diego night, but Linda was dressed more warmly in pajamas. He slept on the side of the double bed nearest the door that led to the stair landing. In the relatively small room, he was also closest to the wall.

The closed door of their bedroom faced Betty Broderick at the top of the stairs. Undaunted, she walked down the hall, going through the open doorway of another room closer to the back of the house. She knew the small TV room led to a bathroom adjoining the master bedroom. From that doorway she would be inside before Dan knew she was there. It was part of her plan that he have no warning of her presence.

Pushing on the door from the bathroom, Betty Broderick stepped into the bedroom. Drapes covered the window, keeping the brightness of the dawn out of the room. She could see only the vaguest shapes of furniture and people. Two years later she wept as she recounted the next few seconds of that morning:

The door to their bedroom was partially openit wasnt closedlike ajarthe motion I made, although I dont think it was a big motion, the movement I made into their bedroom woke them up and they moved. Somebody screamed: Call the police! and I said, No! I just fired the gun and this big noise went off and then I grabbed the phone and got the hell out of there. But I wasnt in that roomit was just an explosion. I moved, they moved, the gun went off it was like Aaahhh !!!it was that fast.

That fast and one explosion, set off by a slight movement, perhaps a scream. Betty Broderick is the only one left alive to tell the story. She remembers only one explosion, but the gun fired five times. Three of the hollow-point bullets hit the two people on the bed. The police found two more bullet holes, one in the wall beyond the bed and one embedded in a bedside table.

Betty Broderick insisted she didnt remember pulling the trigger five times or even aiming the revolver she was holding. The curtained room was dark, the furniture only dim shapes, and she didnt recall seeing the pair on the bed, just what she described as an impression of someone on the mattress near the door as she entered the bedroom. Questioned about those seconds, Broderick explained she had visual memories, like slides, but some of them are blank:

I remember opening the door to the bedroom, so I see myself doing that, but then, I dont see anything elseI know I grabbed the phone, but I dont remember leaving the house or running down the stairs or anything, so its like there are these spots missing. Its like a flash of this and then shes over there and a flash of that

Betty thought she remembered someone screaming, but could not be sure if it was Linda yelling Call the police, or her own anguished howl. I just went Aaagghhh !! I felt like I made a huge scream, but I dont know if I made any noise. It was justjust all sensation. I moved in and they movedthen there was this huge explosion and scream and everything all at once.

Her next visual memory puts her on the other side of the bed, by Dan and the door that led to the stairs and the front door: Im grabbing the phone so he couldnt get on it. I tried to get out of the room, and it kind of jerked and I jerked it back and pulled it out of the wall, and I think I threw it on the top of the stairs.

Behind her, she left Linda Kolkena Broderick sprawled facedown across the double bed, twisted in the bloodstained sheets. One bullet hit the twenty-eight-year-old woman in the chest, a second in the head, killing her instantly. Dan Broderick lay on the floor next to the wall, half under the bed. He had a bullet wound in his upper back that penetrated his lung. Seventeen days before his forty-fifth birthday, he died a few minutes after he was shot, still trying to reach the nightstand phone that had been snatched from his grasp.

The prosecutor in California v. Broderick , Kerry Wells, described the deaths of Dan and Linda as cold-blooded murder. A long-time deputy district attorney in San Diego County and head of the Domestic Violence Bureau, Wells acknowledged no rationalization or provocation for Betty Brodericks actions on that morning in early November, and the lawyer maintained a cold fury as she prosecuted the case for more than two years.