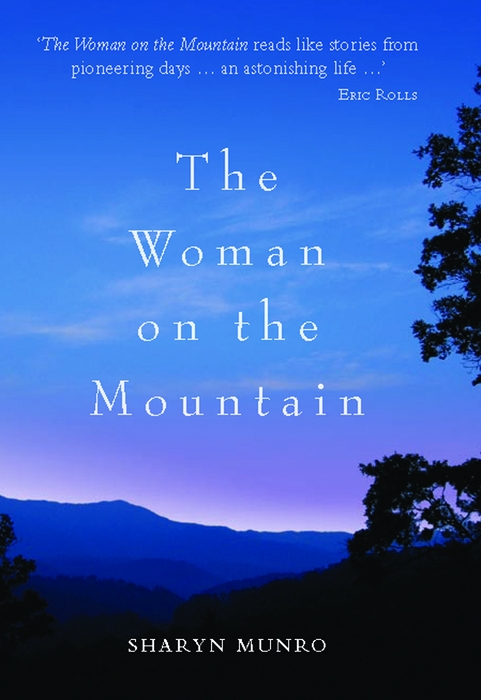

CHAPTER 1

WHY I LIVE WAY OUT THERE

Wherever you live you need to feel safe, and in tune with your surroundings. I do.

Yet my place is a 90-minute drive from a post box, police station, shop or mechanic, let alone a Big M or a Big W or whatever other letter is considered crucial to modern survival. Half of that drive is over a dirt road, partly through a national park which verges on wilderness. I have no neighbours within sight, sound or coo-ee, or not in the accepted sense. My neighbours are the wild creatures who live in the national park.

I have a telephone, but I must take care of my own power, water, sewerage and garbageand of myself, for I live alone. I had never intended to live by myself, way out here in the mountains; I wouldnt have entertained such a foolhardy idea. Youd have to be mad!

Perhaps I was at the time, four years ago, when I made the decision to end my second long-term relationship. My dad had recently died, and I was seeing the whole world differently. That break-up precipitated a second decision: stay here alone, or sell up and leave.

Id first lived here in the late 1970s, with my husband and two young children. Our relatives and colleagues had indeed said we were mad, but we werent alone in following our back-to-the-land urges, just a bit late. Woodstock was long ago, Jimi Hendrix was dead; we hadnt even thought of going to the Nimbin Festival; we owned a Kombi, but it was new and it didnt have flowers on it. We were far too sceptical to be hippiesbut we did read Earth Garden.

For fifteen months we lived in a tent while we made mudbricks and built a small cabin, cooking on an open fire, carting buckets of water up the hill from a nearby spring, showering outdoors under a canvas bag. I absolutely loved the simplicity of it and the closeness to nature.

My husband used to work away from home for a few days each week, often staying away two nights, while the kids and I remained here, with no car and no phone. I was never worriedId done first aid, we were all healthy, and it was too remote for baddies.

But isolation tests a relationship, puts it under stress until any structural cracks show through the civilised veneer. When the marriage failed a few years later, I was as upset by the loss of my simple bush lifestyle as by the loss of my husband of twelve years. Id married far too young, for the wrong reasoninsecurityand to the wrong person. For my foolishness I was then sentenced to thirteen years in the city, bringing up my children on my own, renting cheap, sad houses, and working at a crazy succession of jobs for which my Arts degree had not equipped me.

Every second weekend, if I could afford the petrol, we would drive the four and a half hours to our real home, which we always referred to as the mountain. When the kids had finished school and were so involved in their own lives that I hardly ever saw them, I announced I was going back up there for good.

Amazingly, a phone line had been put in to that remote area by then, under pressure from nervous weekenders. So in 1994 my new partner and I installed solar power and moved to the mountain. With a computer and a phone line, I could keep doing the copywriting/editing for the graphic design studio where Id last worked. He would continue to do guitar repairs and restorations. The plan was that with no rent to pay, growing our own vegies and living frugally, we could make enough for thinly buttered bread at least. In the meantime we would pursue our creative interests, which for me was writing; for him, developing his own handmade classical guitar.

His plan workedthe Kellaway Classical Guitar sounds as beautiful as it looks.

My plan didnt get started for the first four years, as there was always too much else to be done that, being female, I couldnt ignore. We were together here for eight years, during which time this place had etched itself into my very bones. It wasnt really a choice with this break-up; there was no way I could leave. Understanding this, and my grief-stricken state, my ex-partner did not create difficulties.

Having owned the mountain for nearly 30 years, I belonged to it.

Id just turned 55; I had arthritis, which, though under control, restricted what I could do physically. How I would manage, whether I could manage, I didnt know, but I was damn well going to try before I gave up my bush life again. The alternative was too depressing.

Unfortunately, the self-sufficient lifestyle here depends on things that require ongoing work and maintenance, much of which assume either strong wrists or a good relationship with things mechanical, neither of which I possess. There would be many days of frustration and foul language directed at sullen metal objects.

The isolation proved the easiest thing to cope with. Perhaps this is because Im a writer, with my kaleidoscope brain full of people and places and situations demanding I get over here to the keyboard and get on with their storiesso Im never lonely. Only once did I have an intense feeling of aloneness, which is not the same as loneliness. It was the first time Id arrived back here by myself at night. I always tried to get back by twilight to avoid a nerve-wracking trip from town, peering for, second-guessing and dodging panicked marsupials. The Council slash the exotically rye-grassed edges of their long and lonely tarred road; many wallabies and wallaroos are enticed there to grazeand many are killed.

The feeling began almost as soon as I turned off the engine and headlights. Silence. Blackness. Emptiness. I flicked the torch beam about as I walked down to the dark house ... where no one was waiting. After the long drive in around the uninhabited forested ridges of the national park, it hit me: I am totally alone herethis huge forest doesnt give a damn about me! Anything could happen and nobody would know. What am I doing here? Who am I kidding? Im not this brave... and a lot more in the same vein.

Sudden, overpowering awareness of what an irrelevant human dot I was in this vast wild world.

Rushing inside, I lit the fire, sobbing, sniffling, feeling extremely sorry for myself because I would have to leave now I felt like that. But as the familiar cosiness of my cabin settled around me like a childs comforter, the feeling passed. I suppose it had been a flash of panic.

Later, when I went outside and looked up at the enormity of the starry sky, undimmed and undiminished by city lights, I didnt feel overwhelmed. I felt I was in my right place, and grateful to be so.

I once had a similar panicky feeling on a small island, surrounded by sea and with no other land in sight. It was milder but more persistent, and during my stay I had to consciously keep it below the surface. My moment of panic here made me better understand what visitors often evidence when they finally reach my little mudbrick cabin. Theyve been driving for ages, have seen only one house in the last half hour, most likely have taken a few wrong turningsand suddenly there I am, on my tiny patch of civilisation, a clearing in the midst of seemingly never-ending mountain forests. They feel intimidated. One city visitor experienced such anxiety that he had to bolt after only a few hours, instead of staying for the weekend as planned.