Contents

Introduction

OK, Thomas Carlyle, famous and greatly respected nineteenth-century Scottish philosopher, Im going to quote you again, with the purpose this time of completely demolishing what are probably the best-known few words you ever said: The history of the world is but the biography of great men. Wrong, wrong, wrong! And this time I have the whole wide world with which to prove how utterly mistaken you are and were, even in your own time. I wonder that a man of such erudition was so blind to the presence of all those great women, from the past and from his present, who spent their lives in defiance of the conventions that for centuries and across all cultures attempted to confine them to hearth, home and domestic servitude.

Perhaps its simply been convenient for you and for many men like you to ignore the fact that women the world over are, like men, people and not some sort of enslaved lower life form with no purpose other than to breed your children, cook your food and make and mend your clothes. How strange, Mr Carlyle, that at the very time you took up your pen you should have remained oblivious to women across the globe questioning and challenging the status quo. In your own time a woman stood up and asked why it was that, even though she worked, as so many had to or chose to, and was expected to contribute to general taxation, she didnt have the right to vote and decide what kind of government ruled her. Had you, Mr Carlyle, not heard that other familiar saying No taxation without representation? Or, as Susan B Anthony, one of the American leaders of the suffrage movement, put it during its campaign for the vote: Men their rights and nothing more. Women their rights and nothing less. Women of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, after a long and hard battle, finally forced the agreement that, as citizens, we must be acknowledged to have won the right to vote and take a full part in democracy.

In the UK, universal suffrage for all women and men over the age of twenty-one was granted in 1928. Britain was a good way down the list of countries that finally gave in to the fact that so many men, and indeed, some women, had found so difficult to believe: women and men are equal citizens. New Zealand was the first, in 1893, quickly followed by Australia in 1902 (although Aboriginal women were excluded and did not win the right to vote until 1962). Finland, Norway, Denmark, Canada, Austria, Germany, Poland, Russia, the Netherlands, the United States and Sweden all came before Great Britain. Other countries you might have expected to be quick off the mark lagged behind well into the twentieth century; women in Switzerland won the right only in 1971.

Saudi Arabia came to its senses regarding the vote in 2011, and in 2018 the countrys young Crown Prince, Mohammed bin Salman, heir to the throne, began his moves to drag the Kingdom into the twenty-first century. Women, who until now have been denied the right to drive a car, will be permitted to be behind the wheel later this year. There remains, however, a significant restriction on the free movement of what the Kingdom continues to regard as the lesser sex. In conversation with a Saudi professor of womens studies, Hatoum al Fassi, at a literary festival in Dubai this spring, I learned that the guardianship rule, which dictates that a woman must be accompanied by a man when she appears in public, still applies. It is, she told me, essential that the law be changed and written down clearly so there can be no argument or debate about a womans right to personal freedom. This would, she said, be the most important step towards changing the culture. The Princes plan to open theatres and cinemas, banned for the past thirty-five years, will also be significant in introducing more liberal ideas to the society. Art, she believes, will change womens lives.

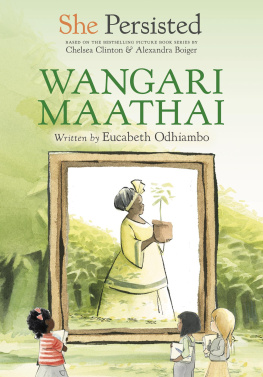

All over the world, there is still a long way to go for women and girls. As Hillary Clinton, who has her own chapter in this book, said, Women are the biggest untapped reservoir of talent in the world. In this collection of twenty-one of that reservoir a tiny number when you trawl the entire globe, venture back in time and discover how many women have simply said no to the limits placed upon their hopes and dreams I have tried to include as wide a range of clever, talented and determined women as possible. There must, I felt, be politicians, writers, artists, musicians, scientists and athletes, and there must be women of different ethnic backgrounds.

Its always necessary to emphasise that feminism and the fight for womens rights is not only the concern of white middle-class women. Intersectionality, the somewhat awkward word coined in 1989 by an American professor, Kimberle Crenshaw, means certain groups of women have to navigate multiple layers of discrimination. For instance, a black woman may have to deal with both sexism and racism, and the feminist movement has to account for class, race and gender when seeking to improve womens lives.

I have to admit that the word intersectionality caused me one of the most embarrassing moments of my broadcasting career. I was interviewing Professor Crenshaw and asked her why shed chosen such a difficult word to introduce what is, in effect, a pretty obvious concept. What exactly did it mean?

Well, she said, its a crossroads, its where these problems of race, class and gender intersect.

Of course, I mumbled, blushing. We are indeed two nations divided by a common language. The penny had dropped Americans dont have roundabouts and their crossroads are commonly called intersections. I really should have cottoned on quicker! What unites my chosen twenty-one is that each has faced seemingly insurmountable obstacles to achieve her ambition, regardless of her colour or class.

Its also important to emphasise that the women in this book are my personal choices and, inevitably, lots of truly great women will have been left out. In some cases, I have been privileged to meet the women, as a result of my thirty years as presenter of the BBCs radio programme Womans Hour . They have impressed and influenced me beyond measure. Some have raised their heads so high above the parapet that they have faced ridicule, torture, and in some cases assassination, for having dared to pursue their beliefs and challenge male authority.

I hope this book will go some way to demonstrate how widely womens fight for justice and recognition of their human rights has spread, and how long its been going on. In the twenty-first century, we often speak of role models. It is my passionate desire that others male or female, young or old should learn of the determination and courage of so many women throughout the history of the world. They should be known, remembered, cheered and emulated by we who follow them.

Pharaoh Hatshepsut

c.1500 bce c.1458 bce

It was on a trip to Egypt in October 1988 that I came across the legendary figure of Hatshepsut, the first woman in recorded history to hold real power and certainly the first woman in ancient Egypt to have declared herself a Pharaoh a regal position strictly restricted to men. A producer, Mary Sharp, and I had been asked to travel to Cairo to put together a Womans Hour programme on gender issues in the country.

Hosni Mubarak took over as Egypts President after the assassination of Anwar Sadat in 1981. He had outlawed the more extremist Islamic groups that had been pushing for stricter control of womens freedoms, so our programme examined what was going on in the lives of ordinary women. Why were so many beginning to wear the hijab, or head scarf? Was it a fashion statement or the return of a religious requirement? Why was the genital mutilation of girls still so common, even though it had been made illegal? Why was Egypts family court described as the most backward in the world? And why was violence against women and girls a common occurrence?

Next page