Tales of

Canyonlands

Cowboys

Tales of Canyonlands Cowboys

Richard F. Negri

Editor

Foreword by

David Lavender

Utah State University Press

Logan, Utah

1997

Copyright 1997 Utah State University Press

All rights reserved

Utah State University Press

Logan, Utah 84322-7800

Typography by WolfPack

Cover photograph: Ned Chaffin in Ernie Country, 1938; courtesy of Ned Chaffin.

All photos in the text are by the author unless credited to another source.

ISBN: 978-0-87421-800-8 (paper)

ISBN: 978-0-87421-801-5 (e-book)

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Tales of Canyonlands cowboys / Richard F. Negri, editor; foreword

by David Lavender

p. cm.

ISBN 978-087421800-8 (paper)

1. CowboysUtahCanyonlands National ParkInterviews.

2. Canyonlands National Park (Utah)Description and travel

Anecdotes. 3. Ranch lifeUtahCanyonlands National Park

Anecdotes. I. Negri, Richard F., 1926

F832.C37T35 1997

979.2dc21 974900

CIP

Illustrations

A much-appreciated thank-you

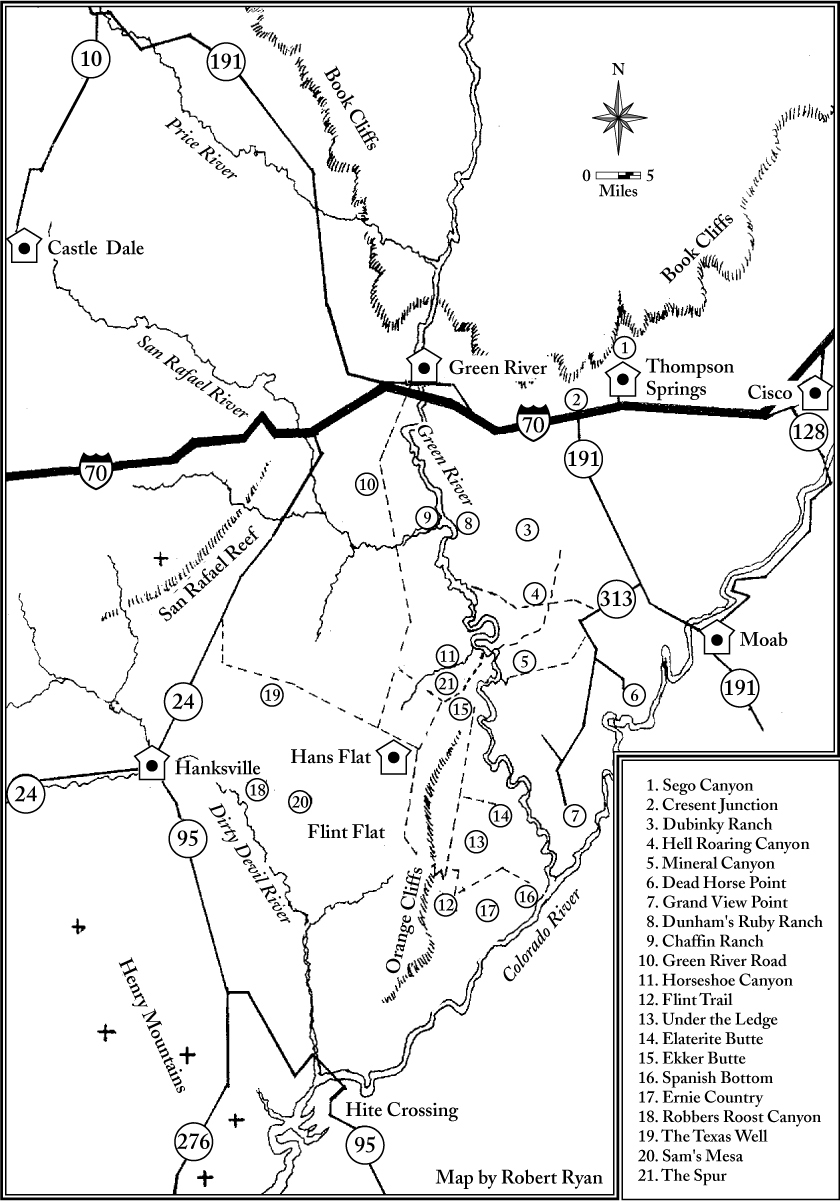

Maps

The Western Canyonlands Region.

Foreword

Hanging On

David Lavender

If you ever have a youngster

And he wants to foller stock,

The best thing you can do for him

Is to brain him with a rock.

Or if rocks aint very handy

You kin shove him down the well;

Do not let him be a cowboy,

For hes better off in hell.

Gail Gardener, Arizona cowboy poet

As a practiced old-timer, I read with interest the tales Richard Negri extracted from seven men and three women by means of a tape-recorderoral history, the process is sometimes called. Since a good deal of the significance of the tales depends on their stern setting, Ill risk condensing some of what Negri has already said about the backdrop. The reason will become apparent as we thread our way through the rock jungles on both sides of Canyonlands National Park.

If you enter Negris territory, as Ill call it, in an automobile, youll soon find yourself immersed in a broad expanse of brush and fragile desert grass. At first the countryside appears either flat or slightly undulant. Actually, it is seamed here and there by rimrocked canyons, blistered by red buttes, embroidered by pion pines and runty junipers. It stretches eastward from the whale-shouldered San Rafael Swell and the Waterpocket Fold to a sudden long drop into hidden benchlands guarded by tumults of stone. The lower area is known locally as Under the Ledge. The Ledges drainage, such as it is, funnels quickly into the placid twinings of the gray-canyoned Green River.

The first tale I want to mention deals with an errant cow that fell irretrievably from one of the Ledges hair-raising trails into a cluster of crags and boulders. Since she could not be moved, she faced a slow death from choking. As used throughout the Canyonlands area, choking means dying of thirst. To prevent that, one of the cowboys Negri tells about clambered down beside the animal and sawed through her jugular vein with his pocket knife. Clearly he thought quick deaths preferable to slow ones, a mercy forbidden to humans.

Another story tells of a cowboy slowly riding toward his own death by choking. The 110 degree heat was reflecting mercilessly from the bare ground and naked stone cliffs when he chanced across a thin patch of damp sand. Dismounting, he managed to scratch a shallow trough in the soil. One faint hope: he lay motionless in the depression. Slowly his body absorbed enough moisture from the earth to let him continue his ride to a surer source of water. Choking cow, choking cowboy: there are ironic equities in the desert.

The riders, though, could bring balance to their lives by indulging in their favorite sports. Their playing fields were the semicircular bottomlands carved out of the lower cliffs by the meandering Green River. At certain seasons, deer congregated in the back parts of those canyoned bottoms. Aware of this, two or three riders would pick a rough way down into a place chosen in advance. Shooting was permissible, but the real sport was roping a high-antlered buck in full flight before it crashed through the brush into the river. More throat cutting followed, preparatory to butchering. Incredibly, we are assured, a good horse can outrun a deer every time, provided, of course, the horse doesnt stub a toe jumping a boulder and so turn himself head over heels.

The wives, meanwhile, stayed at home with the children, packing in stove wood and water while their husbands were away. Routines were similar. Each woman canned beef in old-fashioned pressure cookers, prepared crocks of sauerkraut, tied bandages onto scraped shins, and laundered the menfolks pungent long johns, socks, shirts, and Levis by scrubbing them back and forth, back and forth, over the metal corduroys of her washboard. How she hailed that first gasoline-powered Maytag washing machine! She also moved supplies, when necessary, in the ranchs stuttering, slat-sided Model-T flatbed truck, wondering how long it would be before one of the thin, bald tires blew. If an extra hand was needed at branding time or for driving a few head of cattle from one overused swale to another, she provided it.

Richard Negri diligently recorded all this, even after one of the people he was interviewing remarked, Oral history means we can tell you whatever we want. To flesh out the reminiscences, he gathered suitable photographs. Most chapters include their own maps. In short, Negri has done what he set out to do.

Still, I continue to puzzle over one factor. The country Negri concerns himself with had been settled during the 1880s. A generation passed before the characters he lays before us were born. Most of them spent the major part of their lives in or near the region where the recorder found them. (An exception: the Seely brothers left Negris territory when they were still young. One brother found a wife and both prospered elsewhere, raising sheep in the kindlier climes of northwestern Colorado. Lets remember, though, that the brothers were descendants of a famed pioneer, Orange Seely, weight 320 pounds, who led the first colonists into what became Emery County, some miles north of Negris chosen area. Orangeville is named for him. Reputedly his wife blasphemed on stepping down from their wagon, Damn a man who would bring a woman into such God-forsaken country. So the spirit is there, even if time and geography are stretched a little.)

To resume: except for one drifter, the people who told their tales to the inquiring reporter knew, or should have known, the onerous demands that would be imposed on them by the land they settled in. Inevitably, then, questions arise. Why did they stay here? What made them believe they could achieve fulfillment here?

While I was mulling over these questions, an extraordinarily visual epiphany appeared to me. It took the form of a heavy-shouldered, slightly stooped, slab-cheeked rancher whose blue eyes could pierce a forgetful hand or bothersome government official with the force of a cactus thorn. To me, thirty-seven years his junior, he was always Mr. Scorup. To his contemporaries, he was Al. His full name was John Albert Scorup.