If thou hast any sound, or use of voice Speak to me.

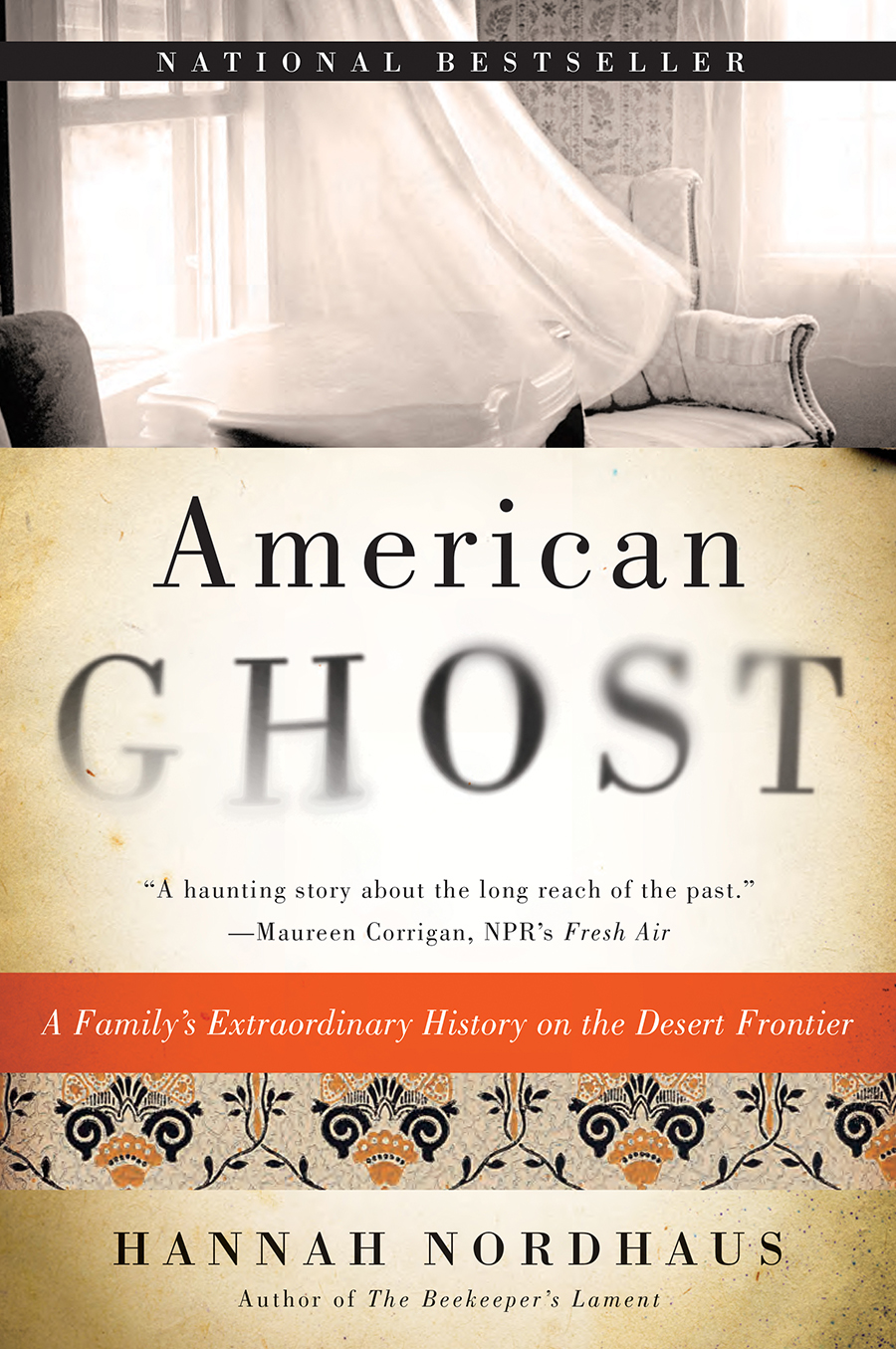

The Staab mansion, Santa Fe.

Paul Horgan, from The Centuries of Santa Fe, 1956, Courtesy of Special Collections and Archives, Wesleyan University.

I t began late at night, as these stories do. It was in the 1970s, at a hotel in Santa Fe, New Mexico. A janitor was mopping the floor in an empty downstairs room. He looked up from his bucket and saw a dark-eyed woman standing near the fireplace. She wore a long, black gown, in the Victorian style of a hundred years earlier, and her white hair was swept up into a bun.

She was also translucent. Through her vague outline, the janitor could see the wall behind her. She was there and yet she wasnt. She looked into his eyes, and the janitor worried that he might be losing his mind. He looked down and told himself to keep mopping. When he looked up again, she was gone. She had possessed, he told a local newspaper, an aura of sadness.

The janitors account was the first the world would hear of the shadow woman in the hotel, but it would not be the last. Some days later, a security guard saw the same woman wandering a hallway. He took off running. A receptionist later saw her relaxing in an armchair in a downstairs sitting room: there, then gone.

Strange things began to happen in the hotel. Gas fireplaces turned off and on repeatedly, though nobody was flipping the switch. Chandeliers swayed and revolved. Vases of flowers moved to new locations. Glasses tumbled from shelves in the bar. A waitress not known for her clumsiness began dropping trays, and explained that she felt as if someone were pushing them from underneath. Guests heard dancing footsteps on the third story, where the ballroom once had beenthough the third floor had burned years earlier. A womans voice, distant and foreign-sounding, called the switchboard over and over. Hallo? Hallo? Hallo?

The woman was seen all over the hotelin the oldest part of the building, the newer annex, and even the modern adobe casitas that dotted the gardens. One room, however, was a particular locus of activity. It was a suite on the second floor with a canopy bed and four arched windows that looked out to the eastern mountains. Guests who stayed there reported alarming events: blankets ripped off in the middle of the night, room temperatures plummeting, dancing balls of light, disembodied breathing. Doors slammed; toilets flushed; the bathtub filled; belongings were scattered; hair was tugged. People sensed a presence. Some also saw a womanthe same wan, sad womanin the vanity mirror, brushing her disheveled white hair.

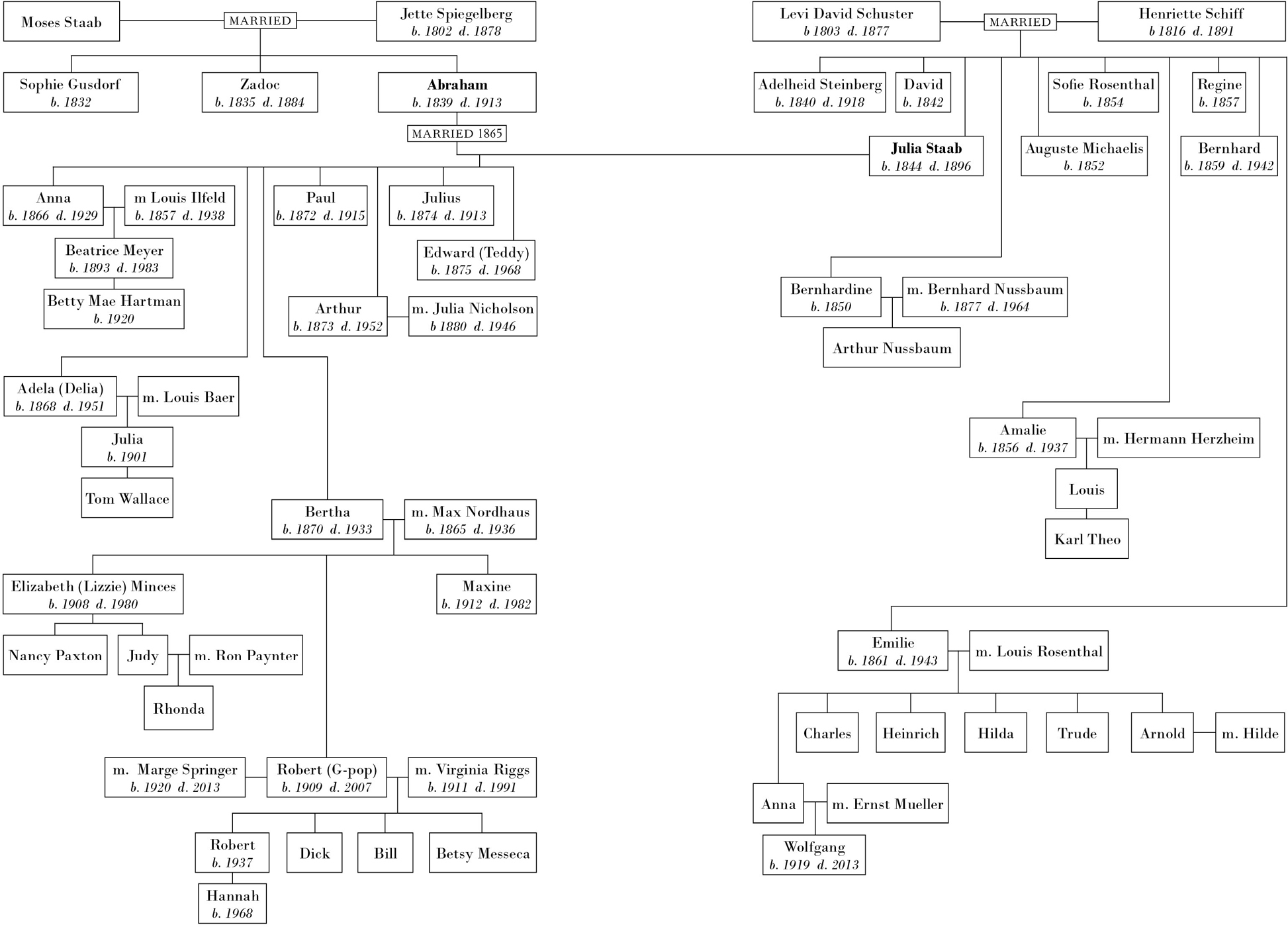

The hotel was called La Posadaplace of restand it had once been a grand Santa Fe home. The room with the canopy bed had belonged to the wife of the homes original owner. The employees of La Posada were certain that this presence was the spirit of that woman, and that she was not at rest, not at all. Her name was Julia Schuster Staab. Her life spanned the second half of the nineteenth century, and her death came too soon. She is Santa Fes most famous ghost. She is also my great-great-grandmother.

Julia Staab occupies a distant point on my fathers family treemy paternal grandfathers maternal grandmother. She came from Germany with her husband, Abraham, a Jewish dry goods merchant who made his living selling his wares on the Santa Fe Trail. Julia was the young bride he brought over from Germany after he made his fortune. It is said that he built his housewhich became the hotel after it passed out of our familyfor her. It was a graceful French Second Empirestyle home on Palace Avenue, a few blocks off Santa Fes main plazaa brick structure in a city of mud and straw, with a green mansard roof ridged with elaborate ornamental ironwork. Julia, too, was formal and elegant, imported from Europe and equally out of place in the rough West: perhaps the house was Abrahams way of making her feel more at home.

I visited La Posada from time to time as a child. My father had moved as a young man from New Mexico to Washington, DC, where I spent my childhood. But we would return each August, when the afternoon drama of mountain thunderstorms painted the desert grasses a gentle green. My parents, my brother, and I would roam through downtown Santa Fe, testing out cowboy hats in the novelty shops that lined the Plaza in the 1970s before the city became fashionable. The hotel was just a few blocks from Santa Fes ancient heart; we would stop in and look around. The old brick veneer had been covered by stucco to match the rest of the city, and the lush gardens were now pocked with guest casitas. But the interior was little changed from how it must have looked in Julia Staabs timedark against the brash high-desert sun, cool, filled with Victorian flourishes that still impressed: molded ceilings, ornate brasswork, gleaming mahogany.

I knew, as a child, that Julia had lived in that house, and that the Staabs had once been a prominent family in Santa Fe. They were historical figures in the city, who had brought money and European manners to a place that lacked both. Abraham hosted lavish soirees in the house; Julia played the piano beautifully and spoke many languages. The family had been written up in regional history books; there was even a street named after them in downtown Santa Fe. The mansion was a local landmark. I knew from my father, who was proud of his familys long history in New Mexico if not terribly interested in the details, that Julia and Abraham had raised seven children in the house. His grandmother, my great-grandmother Bertha, was the third.

Beyond that, I knew little of Julias life. She had lived and died long before I was born, long before even my father and grandfather were born. Although I knew that she had come from Germany, and that her husband had arrived in Santa Fe after New Mexico became a US territory in 1850, I didnt know exactly when or from where. I knew neither how old Julia was when she came to America, nor when she had her children, nor when she died. I knew nothing about her personality and temperament. And I didnt particularly careI was a child; hers was the story of someone old and dead.

It was around the time I was ten or eleven years oldin the late 1970sthat Julia stopped being quite so dead. A cousin who lived in Santa Fe began hearing stories from neighbors about the shadow woman who popped up in the La Posada sitting rooms and pestered guests in Julias former bedroom. And accompanying those tales were intimations of a more dramatic nature about Julias life. Our New Mexico relatives reported hearing rumors around Santa Fe about how Julia had been sickly and deeply depressed, an unhappy bride in a mail-order marriage, shipped against her will or against her grain from the civilized land of her European childhood to the sun-baked hinterlands of the New World.

Julia had suffered in the house, according to the gossip that floated, ghostlike, from Santa Fe bar to restaurant to gallery to stuccoed home. She had lost a child in the room above the La Posada bar and had shut herself in her chamber for weeks. When she emerged, her once black hair had turned completely white. The child was her undoing, the rumors said: after the loss, she became a shut-in. She took to her room and stayed hidden away until she died. Nor was her death peaceful: she killed herself, the stories saidhanged from a chandelier, or overdosed on laudanum. Perhaps she was murdered.