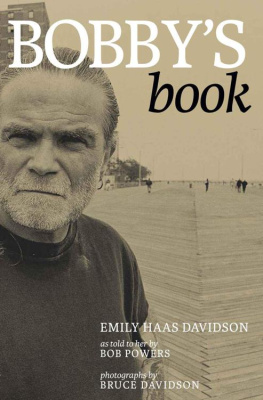

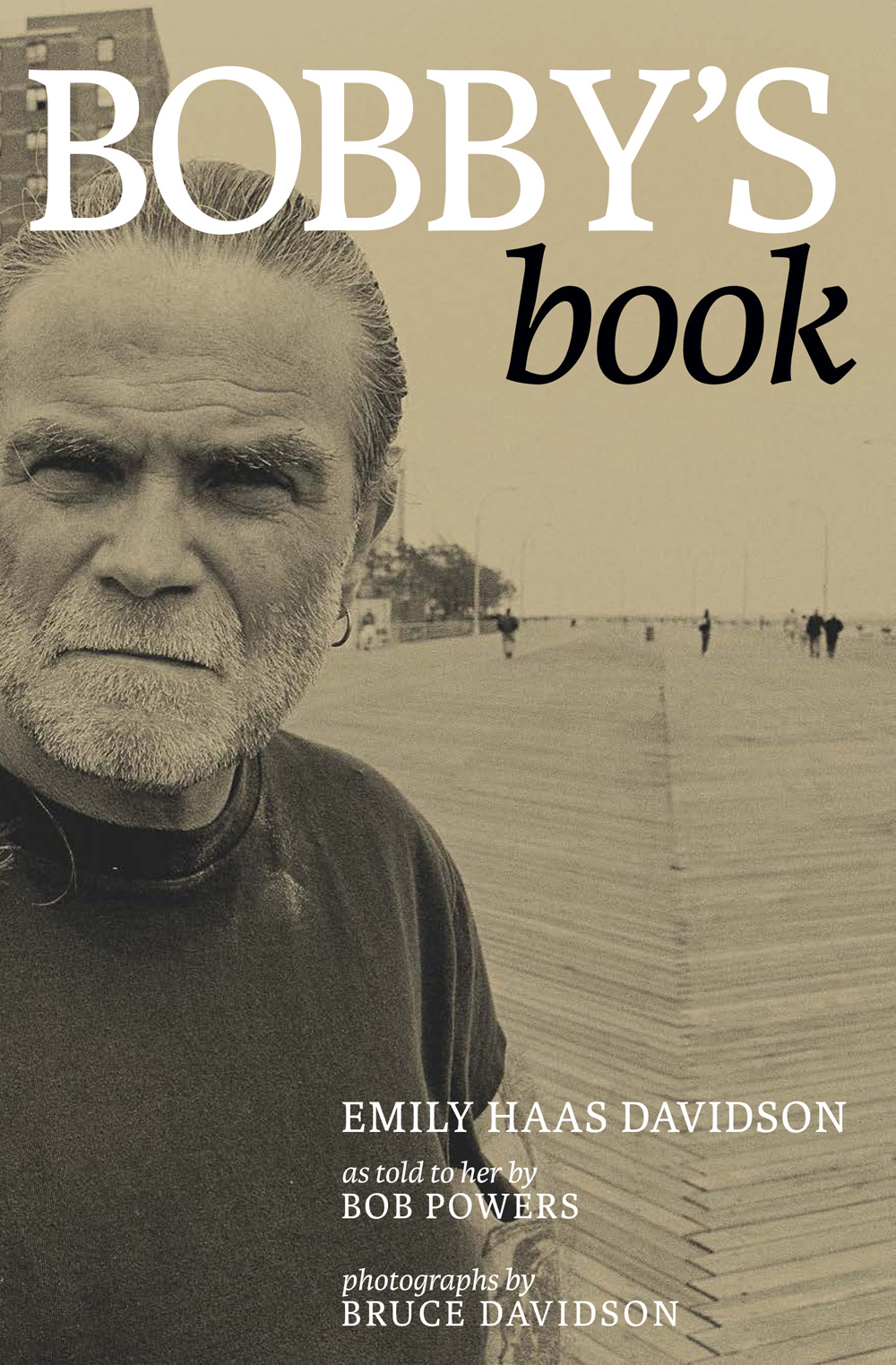

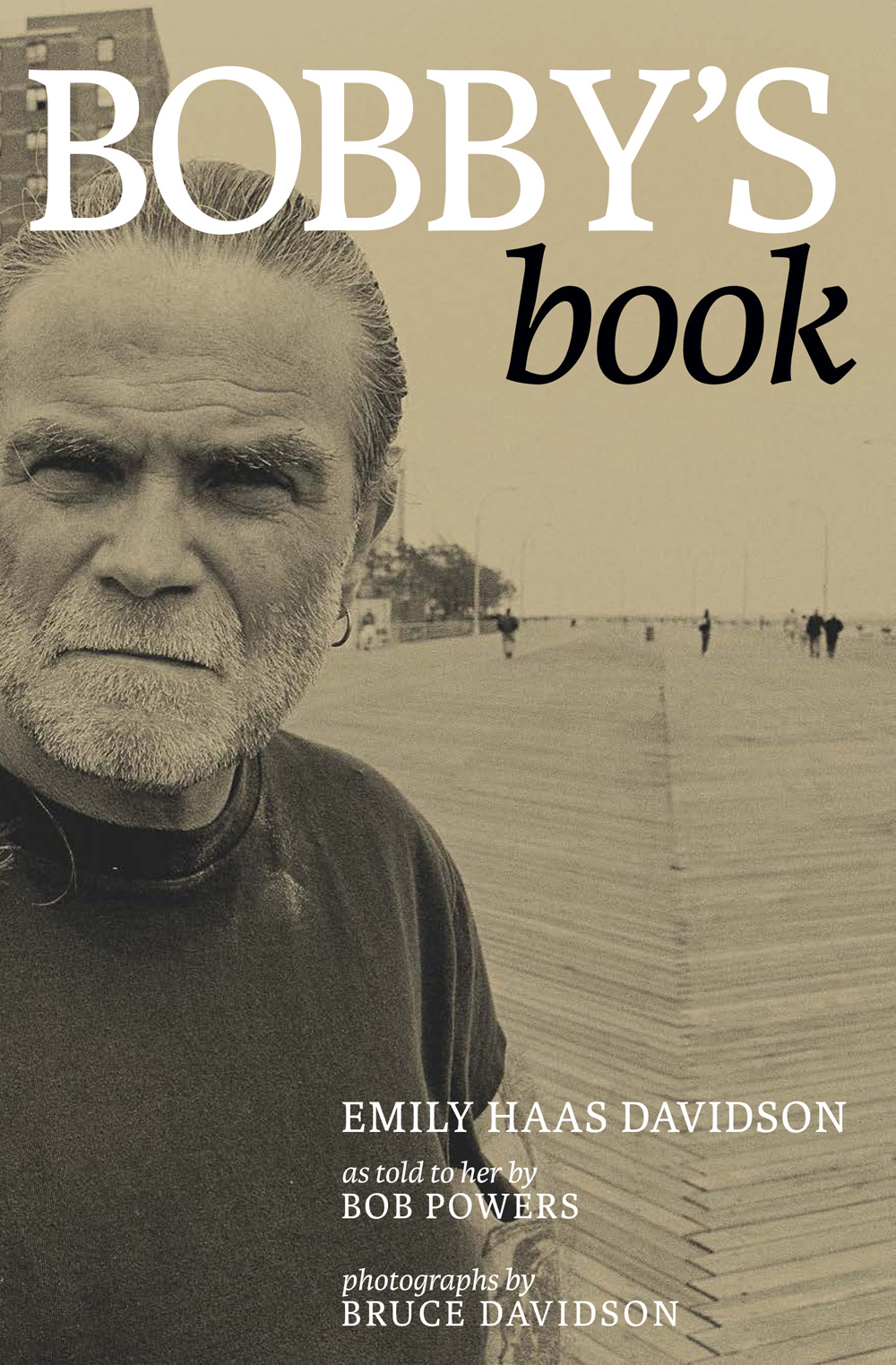

BOBBYS

book

EMILY HAAS DAVIDSON

as told to her by

BOB POWERS

photographs by

BRUCE DAVIDSON

Seven Stories Press

New York

Copyright 2012 by Emily Haas Davidson

Photographs 2012 by Bruce Davidson

A Seven Stories Press First Edition

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, includin g mechanical, electronic, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

Seven Stories Press

140 Watts Street

New York, NY 10013

sevenstories.com

Library of Congress cataloging-in-publication data

Davidson, Emily.

Bobbys book / Emily Davidson and Bob Powers ; photographs by Bruce Davidson. -- Seven Stories Press 1st ed.

p. cm.

ISBN 978-1-60980-448-0 (pbk.)

1. Powers, Bob--Health. 2. Substance abuse--Patients--United States--Biography. 3. Recovering addicts--United States--Biography. 4. Recovering alcoholics--United States--Biography. I. Powers, Bob. II. Title.

RC564.D378 2012

362.29092--dc23

[B]

2012025380

Photographs by Bruce Davidson

Printed in the United States

9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

for

Bruce

who opened

my eyes

Jenny and Anna

who opened

my heart

Bay and Cove

Eden and Elias

who opened

my arms

Contents

Bruce Davidson, Summer 1959

Chapter One

The Way Back

There was no way I was nt gonna be a drug addict, no way, no way. I mean Im drinking since Im eight years old, my mother and them used to have parties, we used to take the shots in the bottles and sip it, sip it, get a little buzzy. Everybody in the neighborhood drank, they were the role models. There was no direction, there was no principles in peoples lives, people were poor, people did the best they could, and on Fridays and Saturdays they went to the bars on the corner and rewarded themselves with a couple of six-packs of beer and a bottle of liquor.

My father used to take me to the bars on Eighth Avenue and Eighteenth Street when I was a little kid and sit me up on the stool and give me a little shot of beer. They used to have a big milk case on the floor for the little kids when they came in so they could play shuffleboard and the fathers could talk at the bar about politics, baseball, the workweek, the bullshit that they did, who worked the hardest, and drink shots of liquor with beer chasers. It was a big deal when I used to go back to the neighborhood and the kids would say, Where were you? and I would say, I was in the bar with my father . Its like going to preschool, before you become an alcoholic, theyre taking you to the bar, theyre showing you where the stool is, theyre showing you theres a bartender, theyre showing you theres cursing and yelling, you mind your own business here. When youre older you get schooled on how to go into bars. I could nt wait till I could go into a bar, slide my little ass on a stool and sit there and have a beer, smoke a cigarette and look at everybody around the room, and nobody d say, Get out, kid, youre too young , or anything like that. It was such a fucking big deal, it was so cool, so cool.

My brothers drank, my sisters drank, and they all hung out in bars and they d be partying. They worked too, but there was ten people living in the house and everybody had an individual life. I see it like a whole chess game and everybodys moving, nobodys bumping into each other because you ca nt or therell be a fight. Then every once in a while theres a bump and a fight breaks out.

If my father did nt come home, my mother would be looking for him and she d be saying, Go get your father, go down to this bar, if he ai nt there, go down to here. If he ai nt there, go over there . I was like a fucking Indian scout, I had to go and get him.

My mother d cook and make dinner the best she could, no matter what it was. She put food on the table even though she was drinking, I do nt care if it was just potatoes or if it was just oatmeal. I can remember eating oatmeal for five or six or seven days in a row, for breakfast lunch and dinner, because thats what we had. She would make apple butter out of apples and icebox cake out of graham crackers with cherry juice and cream and applesauce and she called them icebox cakes. She used to make bread pudding and rice pudding. She d make a big roast when she had money, and everybody would eat. My aunt would come through the door and she would call my mother, May , she would say, May, I smell the corn beef and cabbage all the way from Bay Ridge . We would get a big kick out of that. But the one thing about my aunt is that she knew about my mother. She was the one who sponsored her to come to this country when my mother was young, when she was sixteen. She always helped my mother, she was a great person for my mother to talk to even though my mother would be in the house drinking, or getting drunk and cooking or whatever. My aunt was always there to tell her, May, you should slow down, you should take it easy . Stop, do nt do this, do nt do that . I always knew everything was okay when my aunt was in the house. She d say, Hiya Bobby, how are you? When everybody was calling me Bengie she would call me Bobby , and Id say, Oh, okay, Aunt Lilly, everything is good .

I never really did like my name Robert. They started calling me Bengie when I was around eight years old. One of the older guys on the block, Tommy Conroy, who hung out with my brothers, he called me Bengie like the stray dog in the movie.

I had four older brothers and three sisters, which made us eight. First came my brother Randall, then Billy, then Betty, then Sal, then Margie, then Frankie, then me and then Lillian. There were so many people living in the three-bedroom houseten of us. It was a coldwater flat, we used to have to heat up the hot water to take baths, and we all used the same water. We had a coal stove and me and my brothers would go get oil, the fuel for the kerosene stoves to burn in the wintertime. There was no steam heat, we used to have two or three kerosene burners in all the rooms to heat up the house.

We played on the street between Nineteenth and Twentieth. It was a really busy block. People used to sit out on the stoops. They would all come out in the summertime and be drinking coffee or beer, all kinds of people, Italian, Irish, Polish, some German families. There was an empty lot fenced in with weeds and rubble, across the street was the factory where my father used to work that made medicine cabinets and stuff like that.

On the corner was the delicatessen, Appanels. We used to go down to the store and take a note from my mother or father. Then Mrs. Appanel would give me the stuff and write it in the book. Sometimes when I went down to the store Mrs. Appanel would say she could nt give me anything because the bill had nt been paid. I felt ashamed and embarrassed and would have to go home to tell my mother. She d get mad and sometimes send me back for at least the two beers, cigarettes and bread, and she d say: Until Frank comes home tonight, then shell get the money .

My mother took me to school for the first time when I was seven. Before that I was playing in the house, imaginary stuff, or going places with my mother. She used to take me when she walked my brother Frank the nine blocks to the Holy Name School where my brothers and sisters went and later graduated. One day we went up to Holy Name School and she left me with the nuns. When I got there, no way, I did nt wanna stay, I started screaming and crying but a nun pulled me into the school where I just screamed all day. It was so scary. They tried to shut me up, I kept telling them I wanted to go home. I was just very whimpery, I did nt want to be there, I wanted to be with my mother, and from that day on I never learned anything and never wanted to be there. I went through Holy Name School not learning how to read or write.

Next page