Contents

Guide

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

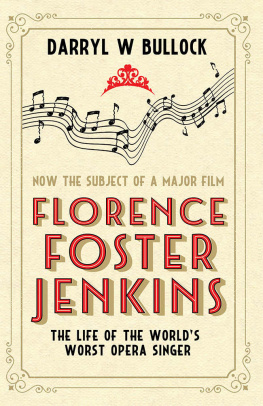

On the evening of Wednesday 25 October 1944 something like two thousand people were shut out of Carnegie Hall. Crowded onto the New York City sidewalk, some waved $20 bills in an effort to persuade their way in, even though the most expensive tickets, long since sold out, officially cost $3. They could only watch as Cole Porter walked through the doors of the most hallowed concert hall in America, there to be joined by the much-loved superstar soprano Lily Pons, and the queen of burlesque Gypsy Rose Lee. Some say they saw Tallulah Bankhead swan in too. The old hall also swarmed with journalists eager to witness a phenomenon.

The night before, Frank Sinatra was on the same stage at an election rally in support of President F. D. Roosevelt. The night after, the New York Philharmonic Orchestra performed under the baton of Artur Rodziski. But on 25 October it was the turn of Florence Foster Jenkins, a sizeable woman in her mid-seventies who had recently released a series of recordings. It was these including her versions of Mozarts Queen of the Night aria and Delibess Indian Bell Song which had created such a feverish thirst to be there.

The evening has no real right to be remembered on so important a day in the history of the world: 25 October 1944 is such a pivotal date that there is a whole book about it One Day in a Very Long War by John Ellis. In the Philippines the Battle of Leyte Gulf became the largest naval conflict in history, in which for the first time the Imperial Japanese Navy deployed kamikaze suicide bombers against US warships. In Europe, the last Romanian city under German occupation was liberated by Romanian and Soviet forces, who also pushed the Wehrmacht from their Norwegian base in Kirkenes, while Bomber Command and the US Air Force took part in daylight raids against Essen, Homberg and Hamburg.

Meanwhile, back in New York, the cover of the recital programme featured a photograph of a stately lady wearing, over short permed brown hair, a tiara with a diadem mounted in the centre. A heavy necklace plunged past her low neckline towards two tentatively clasped hands. On her left hand was a thumb ring. Her eyes were beady and her jaw firm. On a mid-blue background, and under black capitals blazing her name, were the words Coloratura Soprano.

Inside the programme, bona fides advised of previous triumphs. Madame Jenkins, as she liked to be known, possesses a marked individuality in style and piquancy in her interpretations. So reported the New York Journal-American. A Dr B. B. James (publication unattributed) confirmed that a recent audience in the federal capital included persons in the political, cultural and intellectual society of Washington, all of them critically minded hearers. The New York Daily Mirror hailed a personage of authority and indescribable charm whose annual recitals bring unbounded joy.

These notices were in accordance with more or less everything that had ever been written about Lady Florence (another of her preferred modes of address). She had been singing to select audiences since the 1910s, mostly in the protected world of the womens clubs which flourished in great profusion in New York City from the turn of the century. In 1917 she founded her own society and called it the Verdi Club, to whose members she later began singing in an annual recital in the ballroom of the Ritz-Carlton Hotel. Press coverage was not solicited, other than from the Musical Courier, a trade paper whose friendly discretion could be relied upon, indeed bought. The recitals acquired a cult following and, apart from the odd exuberant heckler, for years no one publicly said the salient and obvious thing about Florence Foster Jenkins: that she was a remarkably talentless singer. Instead they cheered and clapped and stifled their guffaws by stuffing handkerchiefs in their mouths.

In 1941 those recordings introduced her feeble voice and drastic pitching to a wider public, and word started to travel. Then came Carnegie Hall. Supported by a pianist, a flautist and a string quartet, she proceeded to massacre a variety of tunes in a variety of outlandish costumes. The three thousand who crammed Carnegie Hall as it had never been crammed before raised such a commotion that her accompanist Cosme McMoon judged the recital the most remarkable thing that has happened there. Her assault on the famous aria from The Magic Flute had all the trappings of a brilliant comedic tour de force as she persistently failed to reach the stipulated notes. But it wasnt meant to be funny, any more than her rendition of Clavelitos, a short, flirtatious song in the Hispanic idiom which pushed the audience to fresh peaks of hysteria. As Florence lobbed rosebuds into the audience from a basket on her arm, one uncontrollable actress had to be removed from her box. In such a frenzied atmosphere it is hard to imagine anyone creating enough of a disturbance to warrant ejection, and yet apparently it happened. The instant demand for an encore meant that poor McMoon had to make his way down into the stalls to retrieve the flowers. The pleasure and the pain was even more intense the second time round. And throughout the evening Madame Jenkins interpreted the gales of laughter and waves of applause as a genuine acknowledgement of her art. Afterwards, her guests mingled with her onstage. Dont you think I had real courage to sing the Queen of the Night again, she said to one of them, after that wonderful recording I made of it at the studio?

The next morning news spread far across the United States. Mme Jenkins, if you havent heard, and the chances are you havent, is a lady who gives song recitals because theres no law against it. That was the Milwaukee Journal. She takes the songs that bring out the best in Lily Pons and permits them to bring out her worst. And the worst of Mme Jenkins, you are herewith assured, is something awful. Earl Wilson of the New York Post reported that Florence Foster Jenkins could sing anything but notes. Hey, You Music Lovers! ran the headline above his report. I Heard Madame Jenkins. Describing her recital as one of the weirdest mass jokes New York has ever seen, his column he was not a music journalist pondered the discrepancy between the serious demeanour of the performer and the unbridled jollity of the audience. On the way out Wilson bumped into a man he described as the singers personal representative, whose name he transcribed as Sinclair Bayfield.

Why? Wilson asked.

She loves music, said St Clair Bayfield, an Englishman in his late sixties who for many years had been a minor Broadway actor. There was only one question Wilson could ask next.

If she loves music, why does she do this?

* * *

People may say I couldnt sing, but no one can ever say I didnt sing. Thats what Florence Foster Jenkins is reported to have said towards the end of her life. It certainly sounds like her. She lived for music and she loved to perform. She refused, utterly and triumphantly, to dwell on her limitations as a singer or to be cowed by those who mocked her. Indeed there is a poignant possibility that Florence simply could not hear those limitations. Audiences certainly rejoiced in her sincerity, and the pleasure she derived from entertaining them. Her performances, by dint of sheer charisma, somehow transcended technique. So inspirational is her example that even the greatest singers have found a place in their hearts for her. In 1968 the young Barbra Streisand was asked by New York magazine which other singers shed like to be: Ray Charles and Florence Foster Jenkins, she said. For Vanity Fair in 2003 David Bowie nominated The Glory (????) of the Human Voice, the RCA album of Florences recordings released in 1962, as one of the 25 LPs that he counted as his greatest discoveries. (The only other soprano listed among all the blues, jazz and rock was Gundula Janowitz singing Strausss Four Last Songs. )