CONTENTS

FOR BILL

FOREWORD

I first heard of the Rowe family in the summer of 1995, when my second child was eight months old. It was a happy time for me. My children were healthy and well cared forand I was incapable of making that assertion without knocking on wood. Why tempt fate? I knew terrible things could happen whether or not I lived up to my parental responsibilities.

I had been exploring various subjects to write about when a friend introduced me to Edith Patt, who for many years had been the chief social worker at the Industrial Home for the Blind in Brooklyn and had a story to tell. In the early 1970s, Edith had organized a support group for the mothers of blind children enrolled in the agencys nursery school. Some of the children had additional handicaps, including severe autism and inexplicable seizures, and there was one case of bilateral anophthalmiaa child who was born without eyes. The women had developed abiding friendships that helped them weather motherhood in its most difficult form. Now their children were grown and the womenthe mothers, as they called themselveswere interested in having someone write about their experiences. Their higher purpose may have been to help others who found themselves in similar straits, but they also wanted recognition for the battles theyd fought on the domestic front. Their struggles may not have had the cinematic glamour of war, but they were as searing to the spirit. While most wars come to an end, caring for a handicapped child is a lifelong obligation.

I listened with fascination and sympathy and admirationand terror. I wasnt sure I was prepared to immerse myself in the heartrending details that would force me to face my worst fears about being a mother. I was still hesitating when Ediths story took an unexpected turn.

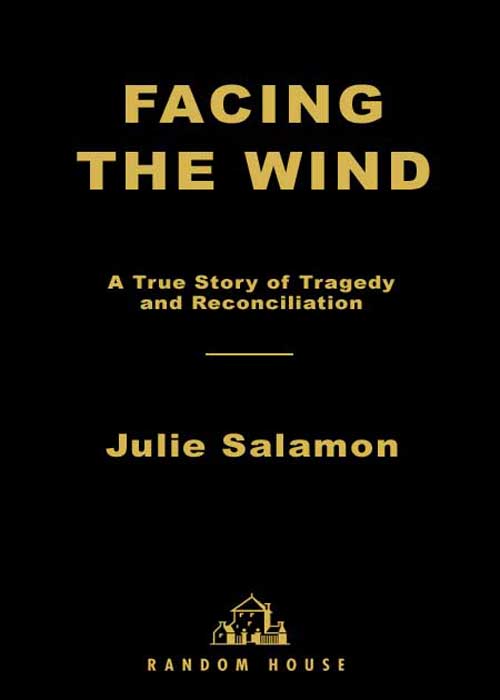

The IHB mothers had become friends because of their children, but they were bound together when one of them was killed, along with her three children. The woman was Mary Rowe. The weapon was a baseball bat. The killer was her husband, and he had always been an exemplary father, a lawyer, a man the women knew and admired. Robert Rowe was declared not guilty by reason of insanity in 1978, spent two and a half years in mental hospitals before being released, and then tried to resume normal life.

It was a monstrous story, but Edith Patt assured me that this was not a monstrous man. I was drawn in. I spent the next four years learning as much as I could about these families, whose lives were yoked by contingency and fate. I interviewed the mothers and their husbands, children, doctors, and social workers. I studied Robert Rowes court records and psychiatric files. I found out that the case had become a legal curiosity, provoking yet another debate about the limits and usefulness of the insanity defense. But I also discovered that for those who were involved, before and after the killings, this was a tragedy, not an intellectual exercise. From it arose a wellspring of questions about responsibility and guilt, retribution and forgiveness: We do what we can to hold chaos at bay, but what if we cant? Why can some people assume responsibilities in trying circumstances; why are others crushed by them?

The narrative that emerged was not uplifting in a conventional sense, though it included moving chronicles of survival and renewal. Nor was it condemnatory, though it contained an act of horrible violence. But in the stories of these mothers, fathers, and children I encountered uncommon strains of human resilience and was gratified, even as I prayed never to be testednot like that.

Prologue

I n the summer of 1977, baseball was the only thing that mattered to Bobby Rowe and Jeffrey Mond. When they werent hitting balls and playing catch, they were listening to games on the radio or rehashing old plays (both theirs and the Yankees) or speculating about whether the Yankees would actually win the World Series. They werent being boyishly optimistic. For the first time in fifteen yearsa lifetime for Bobby and Jeffrey, who were teenagersthere was general agreement that a championship seemed entirely possible.

Bobby and Jeffrey lived in Mill Basin. This was merely a fact of life for them but an accomplishment for their parents, who sounded like real estate brokers when they described this prosperous enclave in Brooklyn as the best of both worlds, with suburban amenities and urban convenience. The fathers of Mill Basin were lawyers, accountants, dentists, and shopkeepers. The mothers were homemakers, though some of them did work outside the house, often alongside their husbands in dry cleaning stores and other family-owned businesses. The population was mainly white and ethnicItalian, Irish, Jewishbut the more liberal residents liked to mention the lovely black family who had moved into the neighborhood (noting with relief that both the husband and wife were doctors).

When Jeffrey heard a game on the radio, hed call Bobby to report the score, and Bobby would do the same for him, even if they were both listening to the same game. When they played catch or shagged flies, theyd pretend to be Yankees starsCatfish Hunter or Ron Guidry or Reggie Jackson. The boys played ball together a lot, even though Bobby, who was fourteen, was exactly four years and four days younger than Jeffrey. Jeffreys mother nagged him about hanging around a younger kid so much, but he liked being with Bobby. Jeffrey was the youngest of three children and Bobby was the oldest of three. It was a novelty to play a different role. Jeffrey could be the big brother and Bobby could be the little one. Besides, they had the same interests. They liked to sail and to climb trees, and more than anything, they liked baseball.

Bobby was the gutsiest kid Jeffrey knew. When he had to use crutches for a couple of years because something was wrong with his hip, hed leave them lying on the ground to climb the giant tree by his house, and then would expertly deal with his mother when she freaked out about it.

Jeffreys affection for Bobby couldnt be disentangled from his warm feelings toward the entire Rowe family. That included Bobbys younger brother, Christopher, who could be a pain in the neck, and Jenna, his little sister, the youngest. One day, when Jeffreys bicycle tire blew out far from home and he couldnt reach his own mother, he immediately called Mary Rowe to pick him up. She was the best lady on their street, as far as he was concerned. And BobRobert, Sr.was the best, period. He had a way of making a summer night in Brooklyn feel like you were at sleepaway camp in the country. Bob taught the neighborhood kids how to build campfires in the backyard and which constellation was which, and sometimes he played the ukulele and sang. None of the other fathers jumped into the Sapolskys swimming pool with the kids, splashing and yelling noisily when they played a game called Whale. Jeffrey certainly couldnt imagine Murray Sapolsky doing that. Mr. Sapolsky didnt play; he yelled. He was always afraid someone was going to drown in his pool. Jeffrey never saw Bob lose his temper.

Jeffrey always felt that when he had children, hed want to raise them the way Bob raised his. He learned so much from Bob. Much as Jeffrey had a good time with Bobby, he also felt as though he were returning a favor to Bob when he taught Bobby things, like how to move quicker when he played ball. Bobby was fast, though not as fast as Jeffrey. The older boy spent hours drilling the kid, figuring out ways to help him put on speed. They worked on it all summer and into the fall. One day Bobby complained that his fathers old bat was slowing him down. It was too heavy. Jeffrey was larger and his bat was lighter, so he told Bobby they should trade. He liked the idea of their having each others bats. What better way to seal a friendship?

Next page