For my beloveds, Here and AfterHere.

You know who you are.

Please read this.

In his 1854 autobiography, American President Martin Van Buren forgot to mention his wife (ne Hannah Hoes), mother of his five sons, to whom he had been married for twelve years. In Journeyman, the autobiography of my first life partner, Ewan MacColl missed mentioning the births of several of his children.

You may have been important in my life, yet you dont appear herein. I didnt forget you. Your scene was most likely cut because someone overran (see Chapter 32, The Occupants of Hell). So you whom I idolise or whom I dearly love, like, dislike, or who might even qualify for inclusion in that chapter you were most likely present in the long, unedited version of this book. I was the one who overran. Ive also had to leave out various awards, Grammy nominations, an honorary doctorate, a flea circus and a sword swallower and friend, Justin Schwartz, who taught his cat to eat vegetables (including Brussels sprouts).

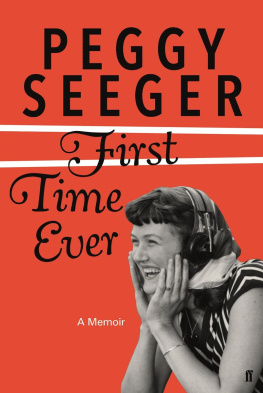

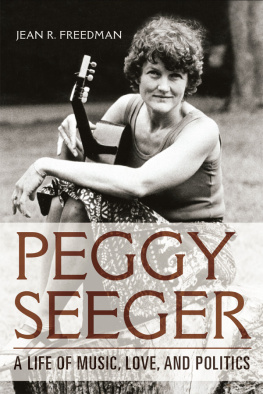

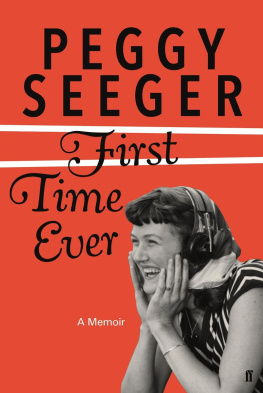

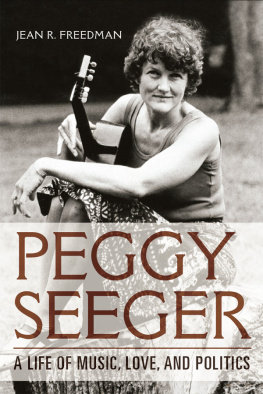

I began jotting down memories for this book in the early 1990s. There got to be so many notes rather like the Post-its on the fridge door that my friend Brian Reese offered to make a long rough draft of them, working towards a proper memoir. I owe him big time for this. I am grateful too for Jean Freedmans biography, Peggy Seeger: A Life of Music, Love and Politics. I used her book as a reference whenever my memory slipped up. Our two books are very different. The biography gives dates, times, facts, etc. It is strictly chronological and uses a plethora of authorised sources, taking us up to 2016. It presents me as I was, as I am. Youd do well to read it alongside this memoir, which presents me as I think I was, as I believe I am. My book roams freely around time, emotions, opinions, prejudices and a lot of whatever.

Memoir memory. I have hardly used old letters and diaries at all they were in the present of the past. This book has been written in the future of that past. Its how I feel now about back then, right up to this morning, when I woke up stiff from yesterdays training at the gym and slightly hungover from two large glasses of red at the Prince of Wales. You do get a rough narrative. I bring in subject-driven chapters when a necessary detour beckons, not for killing Time but for when Time tells me its time to set up my easel and call on my vivid pictorial memory, that enormous gallery of snapshots that lives in my head. The narrative will always resume, so be patient.

Excerpts from some of my songs appear regularly throughout. Unless otherwise stated, all lyrics are mine. Ive put together a CD of some of them, available from my website, www.peggyseeger.com. I am British, so spelling and much of the terminology is British full stop, period. If its easy to find an odd reference (like Board of Inland Revenue v. Haddock), then I generally dont explain it.

Im Peggy. I wrote this book.

Oxford, 2017

Summer, 1955. A barbecue at Butterfly Beach. I didnt fit in. I took off, headed west towards Santa Barbaras year-round Christmas lights. I was running. Ray, my six-foot Californian boyfriend, ran beside me. I would never stop. I would never be tired, hungry or thirsty. We came to a wide, shallow stream. Ray didnt want to wet his shoes. I piggy-backed him over and dumped him on the other side, literally and figuratively. I would never be weak or unable to carry a man. I ran, fusion of inner and outer space, force of nature hurtling forward, my hair streaming behind me, absorbed in the glory of being. I reached Santa Barbara having given birth to reckless optimism and a refusal to regard death as anything but another version of that five-mile flight from one reality to another. I was twenty and immortal.

*

February 1959, England. Ewan, my lover, has gone to see Hamish, his eight-year-old son. I am pregnant with our first child, due in early March. Betsy, Ewans mother, has just arrived to live with us in our tiny upstairs apartment in Purley, Surrey. We are having a companionable cup of tea. In her lovely Scots brogue she comments, haiku-style:

Youll neer get him to leave Jean.

Shes wi bairn, due in October.

Shes a loyal lass.

Her blue eyes have white circles in the middle, milky marbles looking right at me. She knows exactly where her dagger plunged, dangerously close to the babys head. She doesnt know that Im a loyal lass myself.

In the ballads and folk tales, the characters are clear-cut stereotypes, goodies and baddies, facilitated by natural and supernatural in-betweens. Women dont get very good press. Men and girls fare better. I loved the fairy tales. I was the brave mute sister of the seven brothers who had been changed into swans. Knitting the cloaks that would turn them back into men would also revive my ability to speak. Later, I would save my Latin and English teachers, Miss Loar and Miss Fielding, many times from car accidents. A prince was definitely going to kiss me but he wouldnt be forty-four years old, married, with a son and a pregnant wife. So here was Betsy, straight out of a fairy tale, frustrated and vindictive, the size of tuppence, all tongue and temper, short on tenderness. She lived with us for sixteen years, during which time I was steeped in a EwanBetsy world via the traditional method: reminiscence and gossip. I only learned in later life about my own parents, from their very old friends, from my elder brothers, from various publications and from biographies, including my own. But from my mother and father, who gave me a wonderful childhood almost nothing.

Charles Louis Seeger was born in 1886 in Mexico and spent much of his early life there. Simple of speech, not given to tautological perorations, very slow to anger, he was incapable of punishing his children. We called him Charlie. We called our mother Dio the closest my brother Mike could get to our fathers affectionate Ruthie dear. Our parents were different in temperament and class. Even when drawn to anger, Charlies most extreme expletive was Ye gods and little fishes! When Dio became irritated or angry at the chaotic dinner table, he would pat her shoulder, patronisingly, Now, Ruthie dear, dont get peppy. Velvet fist in velvet glove. She would smile and calm from boil to simmer.

Charlie went off to work every day in The Car. Back then, the grilles on automobiles made faces and expressed emotions. Our grey 1938 Chevy had a vertical fish-mouth and a fat ladys rump. If we were still playing in the unfenced yard when Charlie returned in the evening, he would stop at the bottom of the short drive and we would pile onto the running board, a feature now found only as a style accent or as a necessity on high vehicles. Slowly, he would pilot us up the drive and bump the boxes, Charlie! at the end of the garage. If we were in the nightly bath when he arrived, he would lift us out, one by one, and dry us slowly and tenderly on his lap between two towels.

Charlie was skin and bone. The veins on the backs of his hands stood out like blue tubes, as mine do now. We loved to slide those slippery pipelines back and forth under the mottled skin. He was very hard of hearing and would take the little receiver-box from his shirt pocket and hold it near the speaker for clarity. At the dinner table, he would turn his hearing aid off as the family decibels climbed ever upward. Dio would have to handle the battlefield on her own and could get peppy unhindered. Charlies movements were unhurried. I never saw him run. He was incredibly limber and could stand on his head even in his nineties. He exuded inner peace, a quiet that ran through everything he did. He loved my mother with a constancy and depth that shone. She was his