One

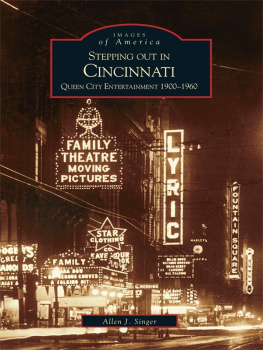

WHERE THE FLICKER SHOWS WERE

At the dawn of the 20th century, the motion picture had just recently made its public debut with the kinetoscope. Hand-cranked machines located in downtown penny arcades showed the minute-long flicker shows through a peephole. Films were soon edited into 5- and 10-minute features, and new projectors put them on screens. The only places big enough to show these photoplays and photodramas were dark storerooms often infested with bugs and mice. These were soon replaced with buildings designed especially as theaters, charging 5 admission. These nickelodeons were clean, comfortable, and vermin-free.

Mostly working-class folks patronized the nickel shows, but general audiences were growing. Programs changed weekly and usually included five different films: a drama, comedy, adventure, novelty, and documentary or other short feature with accompaniment by a live piano or organ. Nickelodeons lasted until around 1910 and were either renovated to accommodate the larger crowds or closed, unable to compete with the big theaters being built around the Queen City.

Folks developed interesting new habits as they got used to stepping out to see the picture shows. They read the title cards out loud. They chatted and shared recipes. Nobody minded, because that was what happened during the show. Prime advertising space was utilized on the screen just like today. In addition to the coming attractions, slides promoting local businesses were shown. The main feature then appeared on the screen and generally lasted an hour and a half, followed by serials, comic shorts, and newsreels. Hollywood studios soon began releasing full-length feature films such as Birth of a Nation in 1915 (shown at the Grand Theater in 1917), and admission rates soared by 10 or more.

These were the days before air-conditioning. Cold refreshments were sold during the shows, and attendants walked the aisles squirting disinfectant to freshen the air. The primitive projection equipment was not always reliable, and the nitrate film was flammable. At the Grand Theater in June 1917, two small explosions occurred in the projector and a fire broke out in the booth. The projectionist extinguished the flames while the audience of 200 calmly filed out to the current melodies played by the organist.

Upon a movies release, distributors sent the films directly to the first-run theaters. Second-run houses received them next, and by the time the films arrived at the small third-run suburban theaters, the abused film had been repaired with chewing gum, safety pins, hairpins, and sometimes even horseshoe nails. The projectionist made repairs before showtime. Whenever the film broke during the show, the projectionist fixed it while audience members booed, yelled, and stomped their feet.

Moviegoers tended to drop a lot of personal articles in the theaters. During comedies, small items fell from their pockets while they were laughing at the slapstick antics onscreen. In melodramas or action films, patrons tore or crushed their belongings in the excitement. Among the items in the lost-and-found bin at the Walnut Theater in 1920 were a porcelain tooth, a stethoscope, gold and jeweled fraternal pins, class pins, a gold watch, watch fobs, earrings, bracelets, a string of beads, scores of eyeglass cases, gold pocket pieces and stick pins, gold and silver cufflinks, shoes, gloves, ties, belts, scarves, fur pieces, pocketbooks, a wallet containing $98, and a purse containing $500. Most of these went unclaimed.

Sound effects like chirping birds and train whistles in early-1920s movies came from a record playing on a specially equipped phonograph, usually poorly synchronized with the film. In 1926, Warner Brothers Vitaphone films introduced high-quality sound and voice on a specialized accompanying record. The first talkie The Jazz Singer , starring Al Jolsonopened in 1927. Lights of New York premiered in 1929 as the first movie to feature all-synchronous dialog. Soon after, theaters that showed the new sound films proudly proclaimed, Not a Vitaphone.