IMAGES

of America

CINCINNATI

THEATERS

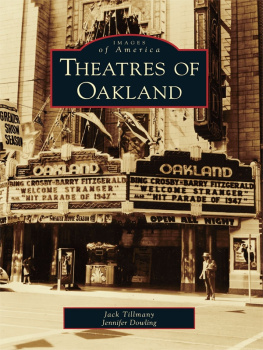

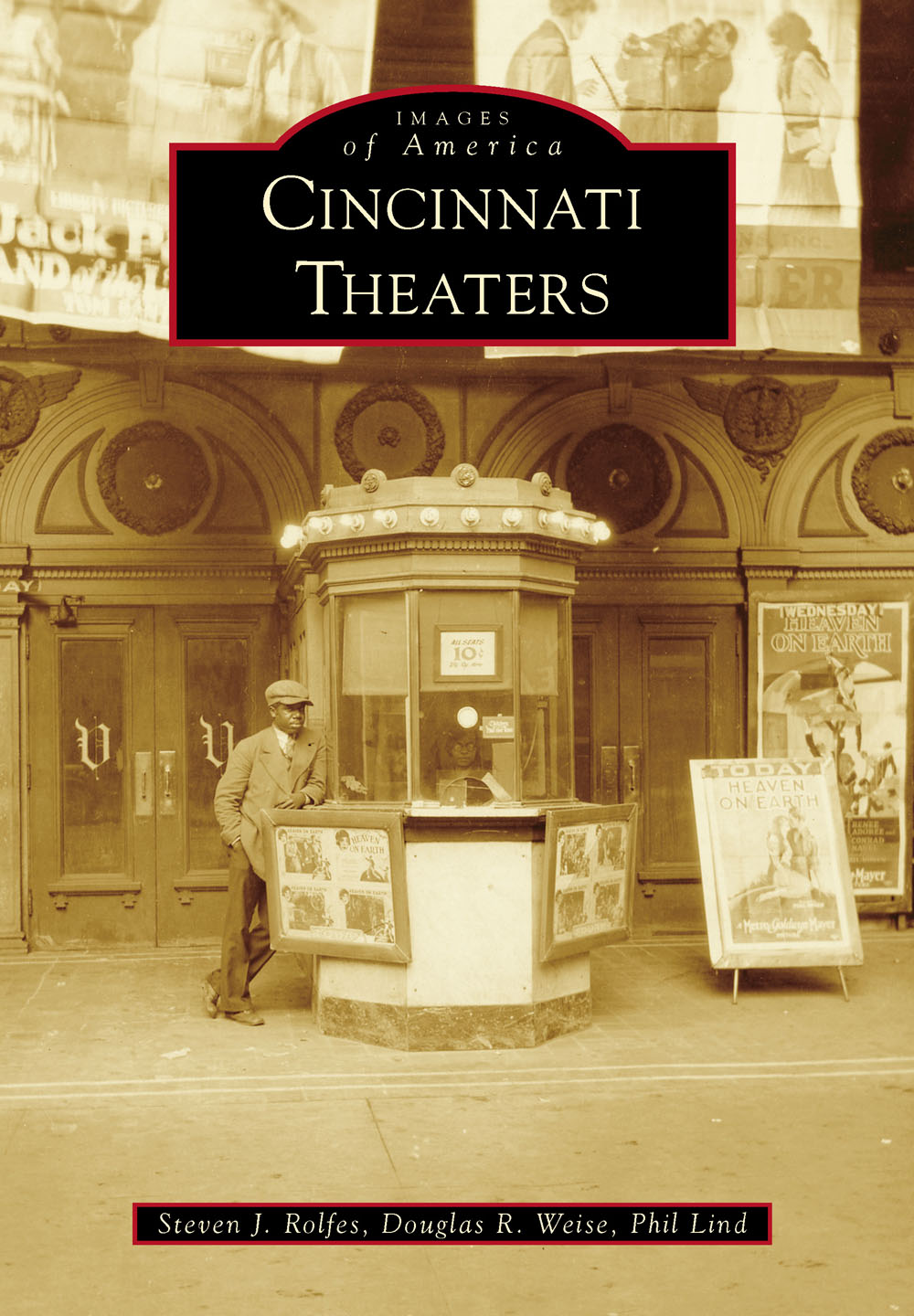

ON THE COVER: No matter how hard life is outside, the neighborhood theater has always been a place to escape the worries and pressures of everyday life. Often, the elegance and unique architecture of these cinemas presented a stark contrast to the neighborhoods around them. (Cincinnati Museum Center, Cincinnati Historical Society Library.)

IMAGES

of America

CINCINNATI

THEATERS

Steven J. Rolfes, Douglas R. Weise, Phil Lind

Copyright 2016 by Steven J. Rolfes, Douglas R. Weise, Phil Lind

ISBN 978-1-4671-1524-7

Ebook ISBN 9781439655658

Published by Arcadia Publishing

Charleston, South Carolina

Library of Congress Control Number: 2015944862

For all general information, please contact Arcadia Publishing:

Telephone 843-853-2070

Fax 843-853-0044

E-mail

For customer service and orders:

Toll-Free 1-888-313-2665

Visit us on the Internet at www.arcadiapublishing.com

To Judy and Isabelle Weise; Terri, Jordan, and Selena Rolfes; and the Lind family

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This book would not have been possible without the help of many very supportive people.

To everyone who had a part in helping us with the research and obtaining images for this project, we say thank you! Special thanks to Diane Mallstrom and everyone associated with the Public Library of Cincinnati and Hamilton County Greater Cincinnati Memory Project and the Southwest Ohio and Neighboring Libraries. We would also like to thank Cierra Earl and the Kenton County Public Library for all the assistance. Thanks also to the Cincinnati History Library and Archives. Thanks to Penny Huber and David Huser of the Mount Healthy Historical Society. Other historical societies who assisted us include College Hill, Catherine Huebner with the Westwood Historical Society, North College Hill, Reading, and Delhi. Thanks to Alicia Krall at the Carnegie, Curtis Trefz, Cincinnati Arts Association, Connie Yeager, the McNamara Collection, the Ray Grothaus Collection, Joe Raphael, Vern Oliver, Pat Kelly, Jim Repogle, Phil Adams, Sharon McCullough, Tom Wernke, Dru Steigert and Ed Miller at the Parkland Theater, Cincinnati Playhouse in the Park, Michel Sheer at the Hilton Netherland Plaza, Mary Casey-Sturk and Sean Mette at Madcap Productions, and Sarah Bradley. Thanks also to Scott Santangelo at Music Hall. Thanks to Jesse Darland, our editor at Arcadia Publishing. We appreciate all your help and encouragement.

We thank our families for all their help and support, especially Jordan Rolfes, of Beagle Rampant Productions, for the beautiful photographs and hours of technical support. Thanks to Isabelle G. Weise for her wonderful photographic contributions. As always, we thank our Lord for his many blessings.

INTRODUCTION

It is impossible to say exactly what the first theater in Cincinnati was. It could have been just a tree stump or a fallen log, an unsteady chair, or possibly the roof of a nearby flatboat that had not yet been taken apart to be repurposed as a cabin. Any structure that would support a fiddler would have sufficed as the Queen Citys very first stage, and the recently cleared open ground could have served as its first ballroom.

Despite the gay music, not everyone would have been drinking and dancing. A few men with loaded muskets would have been standing guard, staring out into the blackness of the surrounding wildwood. They were vigilant for the unexpected appearance of the Shawnees, who would be in no mood for dancing.

It would not always be that way. By 1789, Fort Washington was built to secure the settlements in the Northwest Territory. With the presence of soldiers, the tiny encampment known as Losantiville was destined to become a major city. The next year, the rapidly growing river village changed its name to Cincinnati.

A year later, in 1791, Northwest Territory governor Arthur St. Clair suffered a disastrous military defeat in his campaign against the Indians. As soon as word of this debacle spread, many settlers in remote locations abandoned their cabins and fields, fleeing to the safety of Cincinnati.

Overnight, this sudden influx of new people turned the village into a city. Among the amenities of this remote outpost of civilization were no less than three taverns. The fiddler on the tree stump now had a more traditional setting, and the Cincinnati Theater was off and running.

In 1819, the city directory proudly announced the construction of a real theater on Second Street, to be opened under the management of Messrs. Collins and Jones with a full and respectable corps of comedians. There was no stopping the Cincinnati Theater now!

Cincinnati was still young in 1834 but was quickly becoming the meeting place of the North and the South. That year, Dan Emmett arrived in the burgeoning Queen City. A musician, he carefully listened to the songs of the African American men working on the steamboats and docks and decided to become a soldier. After enlisting in the Army, he was stationed directly across from Cincinnati in Newport, Kentucky. There, he continued his life in music and became part of the marching band. After being stationed in Missouri, where he also listened to African American music, this time from actual slaves, he returned to Cincinnati and left the Army. Around this same time, a New Yorker named Thomas Dartmouth Rice, often known as Daddy, created a character named Jim Crow. A third songwriter, Stephen Foster, was sitting in his room in a boardinghouse at what is now the Guilford Building, where he penned some of the most well-known songs of all time, including Oh! Susanna. The uniquely American form of musical theater practiced by these men became known as the minstrel show.

Emmetts days as a soldier were over, but he still loved music. He joined a circus and began to imitate the music he had heard, performing the foot-tapping melodies under a thick coat of black makeup. His troupe, which donned blackface, called themselves the Virginia Minstrels. Among the songs he penned was one that would later become the anthem for the ConfederacyDixie.

The minstrel show was extremely popular not only in the years before the Civil War but also throughout the Gilded Age and into the early part of the 20th century. In the decades following the Second World War, however, this form of entertainment was regarded as derogatory, an attempt to humiliate African Americans. Today, it is extinct.

While this uniquely American theatrical experience certainly has no place in todays society, one must always be careful of judging the past by modern standards. To understand the appeal of this curious form of entertainment, one must look at the audience. Presented as a diversion to average, hardworking white men and women, the minstrel show was a three-act romp depicting the Southern plantations as a kind of Elysian Fields with stirring music and sometimes risqu comedy. Men would howl at the dandy character who effectively satirized their foremen and factory owners. A life of singing lively songs, dancing, and loafing was presented to the audience.

Of course, it was all a myth. The reality outside the theater door painted a very different picture. The streets of Cincinnatiand all Northern citieswere filled by African Americans who had escaped the bonds of slavery and, later, the brutal discrimination during Reconstruction. They could tell anyone who would listen that life on the plantation was not a song and dance.

Of course, no one was listening. They were seeking escape in a fantasy realm far from the stress and boredom of the everyday world. But, then, that is what theater is all about.

Next page