Design and composition: Richard E. Farkas

Typeface: Palatino Linotype

For whatever reason, I did not feel the world was mine.

Acknowledgments

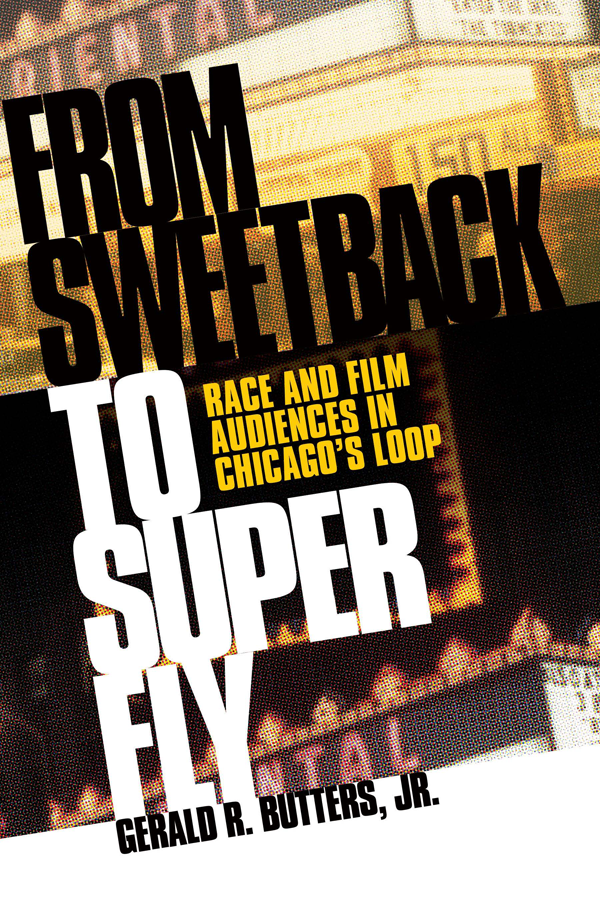

My interest in this project began with two relatively simple questions. First, I wondered what had happened to the grand cavernous movie theaters in the Loop. By the time I moved to Chicago in 1999, not one was still showing films; in fact, most had been bulldozed. Second, I questioned why some suburbanites had such a frightening take on the Loop; many were terrified to either take the L or to simply wander around downtown Chicago. The area had gone through a remarkable transformation by 1999, and I was amazed that suburbanites still had this mentality. These two questions formed the research for this book. This project took many years to come to fruition, and there are individuals I must thank.

First, the coolest part of this project was being able to meet and interview Timuel Black Jr., historian and civil rights pioneer, and Earl Calloway, longtime entertainment editor of the Chicago Defender. I was fortunate to receive a Timuel D. Black Fellowship from the Sylvia G. Harsh Society in order to complete research on this manuscript. This is perhaps one of the highest honors I have received, because it is named for Dr. Black. Both men are generous, kind pioneers and gentlemen of the sort that doesnt exist anymore. I want to be them once I reach their age. I thank them both.

I am also greatly indebted to a large number of librarians and their staffs at multiple institutions, including the Chicago History Museum, the Carter G. Woodson Library, the Harold Washington Library, and Aurora Universitys library. Special thanks to Kay Culhane and Lauren Jackson-Beck.

I am fortunate that several professional scholars whom I consider friends helped me with this manuscript. They include Novotny Lawrence, Jacqueline Stewart, Christopher Sieving, David Gerstner, and Harrison Sherrod. Robin Means Coleman gave me remarkable support and guidance, and I am deeply indebted to her. My colleagues at Aurora University, including Jessica Thurlow, Mark Soderstrom, Martin Forward, Jay Thomas, Henry Kronner, Jonathan Dean, and Mark Plummer, have also been very supportive. I intervieweda number of individuals for this book who were gracious with their time and memories. Special thanks go to Barbara Holt, Sergio Mims, Jim Galezewski, John Danzer, and my good friend Myrna Lovejoy.

This manuscript would have probably not been published without the support of my friend Craig Prentiss, who saved me when I was floundering, and Gary Kass, my editor, who always has patience with me.

I am also surrounded by a group of friends who give me support in ways they are not even aware of. They include Amy Danzer, Brad Potts, Charles Wilson, Isaac Persley, Jim Kinzer, Tim Fox, Anson Christian, Canan Cullins, Randy Jones, Enrique Nieto, Joel Morton, Lee James, Nora Ellen Richards, Ramzi Fawaz, Mark Robinson, Jim and Sharman Galezewski, Stanley Jackson, Jeff Lodermeier, and Maria Montano. And I cannot forget my running buddy, partner-in-crime, and confidant, Denise Hatcher.

I want to thank my family, including Gerald Butters, Sr., Bob and Nancy Butters, Breana Butters, Bryan and Tiffany Butters, Brittney Butters-Costello, Derek Butters, Rachel Balderston, and Greg Mack. And a very special thank you to Andr Meeks.

Finally, I want to thank Jarrett Neal. He has heard the stories in this book too many times to mention, and he has been there for me every step of the way. His support is seemingly limitless. I dedicate this book to him.

Introduction

I have long been fascinated by the occupation of geographic space. Historians and cultural theorists have explored the notion of occupied space since the transnational attention that Englands Birmingham Centre for Contemporary Cultural Studies gave this concept in the early 1980s.

As a film historian I have become interested in the role of the motion picture theater as an occupied space. For the last hundred years, certain motion picture theaters have attracted audiences that were distinct in relationship to their race, sexual orientation, ethnicity, or class. Often these theaters were patronized by individuals who occupied the geographic space or neighborhood in which the motion picture theater existed. But this was not always the case. Some theaters became distinctive because their audiences did not represent the dominant community of the neighborhood. This has been the case in the city of Chicago. The Loop has traditionally been the downtown, the epicenter, of the city. During the early 1970s the major, first-run motion picture theaters in the city were still located in the Loop. But during that time and immediately after, both the Loop and these theaters experienced hard times. The Loop faced many of the problems that decaying downtown regions experienced across the country in the mid-twentieth century. Deteriorating infrastructure and crumbling architecture gave downtown areas the appearance of being past their prime. In the first half of the twentieth

In this study I examine box-office attendance and programming in motion picture theaters in the Loop from 1970 to 1975. I chose these years because they were the heyday of so-called blaxploitation films and because motion picture theaters in the Loop booked films meant to attract an African American audience. I will only be able to begin to explore many questions related to this study, especially, Why did African American audiences suddenly begin attending motion picture theaters in the Loop in the early 1970s? Which came first: African American audiences or motion pictures that were meant to appeal to African American audiences? Did African Americanthemed motion pictures increase the desire of black audiences to attend these theaters? Why did certain theaters in the Loop screen a large number of black-themed films while other theaters played almost none? Were certain theaters thought to be identified with one race or another?

THE LOOP AS SPECIAL EXPERIENCE

In the late 1960s the Loop was the major entertainment district in Chicago, a destination for millions of Chicagoans who were commuting to their jobs or homes. Going to the movies downtown was an event for Chicagoans in the period from 1945 to 1970. Individuals dressed up when they went to a motion picture in the postwar era;

But the Loop was experiencing rapidly changing racial dynamics in this period, and business interests mobilized economically and politically to protect their investments. Because Chicagos major first-run motion picture theaters were located in the Loop, they were the first to screen major Hollywood films; once the studios figured that most interested urban patrons had seen the feature, the film would start showing at neighborhood theaters in Chicago and/or the suburbs. But the exhibition branch of the motion picture industry was learning to exploit the growing suburbanization of the white middle-class movie audience by constructing new suburban theaters and changing distribution patterns.

This paper meets the requirements of the American National Standard for Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, Z39.48, 1984.

This paper meets the requirements of the American National Standard for Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, Z39.48, 1984.