Published by The History Press

Charleston, SC

www.historypress.net

Copyright 2016 by Alan F. Dutka

All rights reserved

First published 2016

e-book edition 2016

ISBN 978.1.43965.675.4

Library of Congress Control Number: 2016931803

print edition ISBN 978.1.46713.646.4

Notice: The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. It is offered without guarantee on the part of the author or The History Press. The author and The History Press disclaim all liability in connection with the use of this book.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form whatsoever without prior written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

CONTENTS

FOREWORD

The camera obscura (dark room), known by the Greek philosopher Aristotle, was literally a large room with a hole on one side that projected light onto the opposite wall to create an image. Centuries later, Leonardo DaVinci used it to help him gain perspective for drawing purposes. The camera obscura was the ancient ancestor of the photograph.

When Joseph Niepce took the first photograph in 1826 on a pewter plate covered in chemicals (exposure time eight hours) and Louis Daguerre demonstrated the daguerreotype process in 1839, preserving an image on a copper plate (exposure time twenty minutes), they introduced a new technology and art form never before seen; it changed the world forever.

But as remarkable as photographs were, nothing captured the imagination and thrilled people more than the invention of motion pictures, or movies, as theyre called today. Movies have influenced and fascinated people from the beginning to the present day. Dreams and illusions, factual history and fantasy, all projected at twenty-four frames per second. In many cases, movies are a reflection of the society and culture. As one British author put it, My mother took me to the silent movies in a spirit of ostentatious condescension and told me theyre nothing like real life and I must not believe them. And she was wrong. Because everyone who comes from England to America and goes back says one thing first: Its more like the movies than youd ever dream.

On a large scale, during the 1930s and 1940s (often referred to as the golden age of Hollywood), movies provided relief and entertainment to a depression- and war-weary nation.

On a smaller scale, there are stories of people who were inspired by a movie and went on to fame and fortune. Charlie Chaplin performed comedy in English music halls until he saw his first flicker, decided to perform comedy on film and became the top silent film comedian of all time, now considered an icon of comedy. Walt Disney was an artist illustrating ads until he started doing ads for films. He switched to making movies, and the rest is history. Liberace started out as a classical piano player. Then he saw the movie A Song to Remember about the life of Chopin. He completely changed his style, adopting the elaborate costumes and candelabra that he saw in the movie, and became world famous as Mr. Showmanship. In 1955, a very young Paul McCartney and John Lennon saw the film Rock Around the Clock and were so excited about this new rock-and-roll music that eventually they formed their own group, the Quarrymen (later the Beatles). Many young girls were inspired to study ballet after seeing the 1948 British film The Red Shoes, and many high school boys decided to study law after seeing Gregory Peck as the lawyer Atticus Finch in To Kill a Mockingbird. The 1985 film The Breakfast Club spoke for a whole generation as no other medium could.

These examples and many others illustrate the powerful effect movies can have on people. This, of course, happened in cities across the country. One of those cities was Cleveland. As a longtime researcher of Cleveland history, the movie theaters of Cleveland have always interested me.

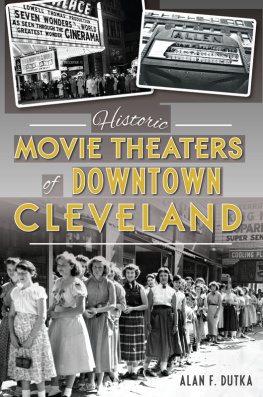

Now, with the latest book by Alan Dutka, we, the readers, are treated to a very thorough, well-researched and detailed history of the movie theaters of Cleveland. Alans skill at digging to the very bottom gives us information of all kinds we cant really find anywhere else. On top of that, he tells the most fascinating, unusual stories about some of the owners, managers, actors and theatergoers, which give the most important part of any history: the human element. When you read one of Alans books, you learn about not only the subject of the book but also many other related subjects. He lets you into a time long ago and far away, and when you finish his book, you are a better-educated person. So lets all read and enjoy Historic Movie Theaters of Downtown Cleveland.

DAVID HORAN

Historian

PREFACE

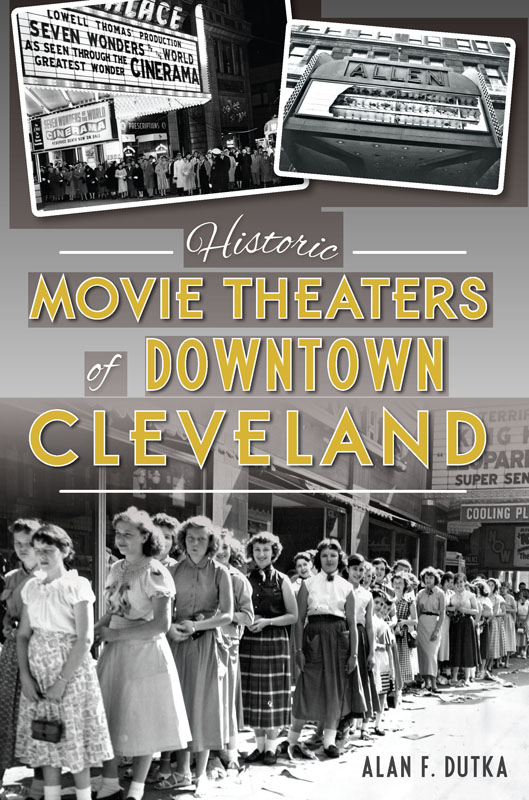

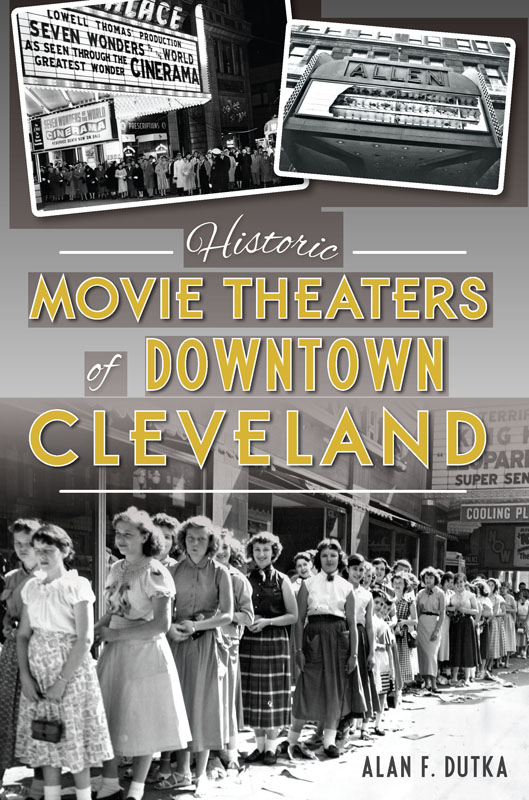

Three months shy of my fourth birthday, I first entered a movie theaternot a neighborhood film house but, rather, the downtown Allen Theater. My father took me to see a reissue of Pinocchio, and the outing created a family crisis. Entering near the middle of the movie, we stayed through the cartoons, news and previews to pick up what we had missed. When I realized Pinocchios adventures would keep returning to the screen, I asked if I could see the film a second timeand then a third time. When we returned home, seven hours after our departure, my panicked mother had just started to telephone the police. In todays world, Im sure it is hard to imagine that just seven years later, my friends and I would attend downtown theaters by ourselves, without any parental supervision.

Working as an usher at the age of sixteen, I watched movies for free and earned money at the same time. Without a doubt, July 17, 1959, marked the highlight of my three-year stint in downtown Clevelands theaters. Among many other duties, I often worked as a doorman at the Stillman Theater. Cary Grant, promoting his yet-to-be-released film North by Northwest, stopped at the Stillman on a publicity tour. Two hours prior to Grants scheduled appearance, I sat virtually alone at the theater door with little reason to expect anything but dullness for at least the next hour. But soon I noticed a distinguished-looking gentleman entering the Stillman from the adjoining Statler Hotel. As he walked up the long lobby, I realized that in just a few seconds I would meet a legendary film star. Grant explained that he wanted to talk with the theater manager to discuss a few logistical issues prior to his appearance. When I told him I constituted the only employee in the theater at the time, he looked straight into my somewhat terrified seventeen-year-old eyes and, with a big smile, asked, Well, would you mind if I chatted with you for a few minutes?

Even in the 1960s, as the downtown movie palaces rapidly declined, I still journeyed into the heart of the city to see many films at the Palace, State, Ohio, Allen and Hippodrome Theaters. Motivated only partly by nostalgia, I recognized that you would always get a good seat at the nearly abandoned downtown theaters, even for the biggest blockbusters. And parking never proved to be a problem because I knew plenty of relatively safe free parking spots.

A few generations later, I now live downtown, no more than a threeminute walk from the Allen Theater where I witnessed my first movie. Although I often attend the beautifully restored Playhouse Square theaters, I have only managed one seven-hour outing since

Next page