Published by The History Press

Charleston, SC

www.historypress.com

Copyright 2020 by Alan F. Dutka

All rights reserved

First published 2020

e-book edition 2020

ISBN 978.1.43967.162.7

Library of Congress Control Number: 2020941937

print edition ISBN 978.1.46714.672.2

Notice: The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. It is offered without guarantee on the part of the author or The History Press. The author and The History Press disclaim all liability in connection with the use of this book.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form whatsoever without prior written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

Contents

Preface

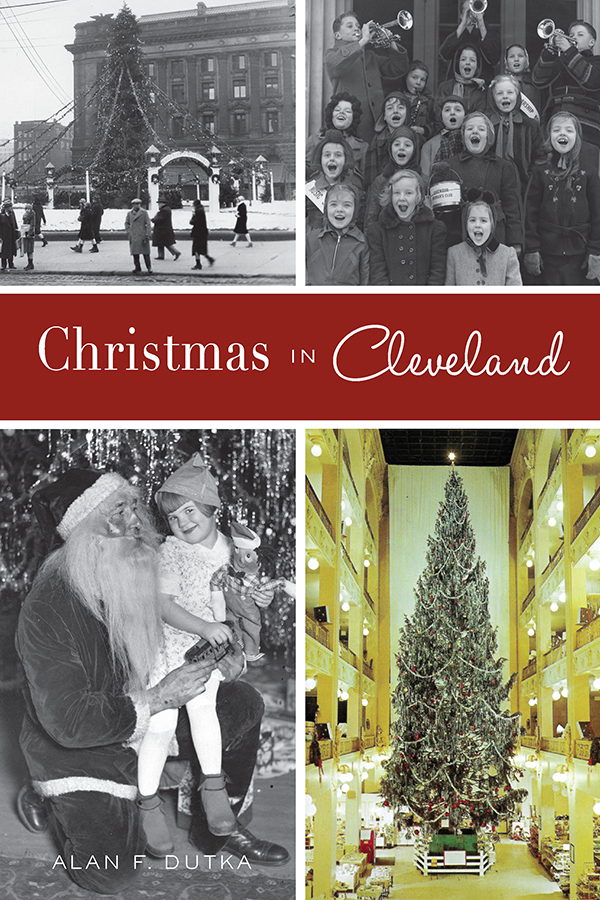

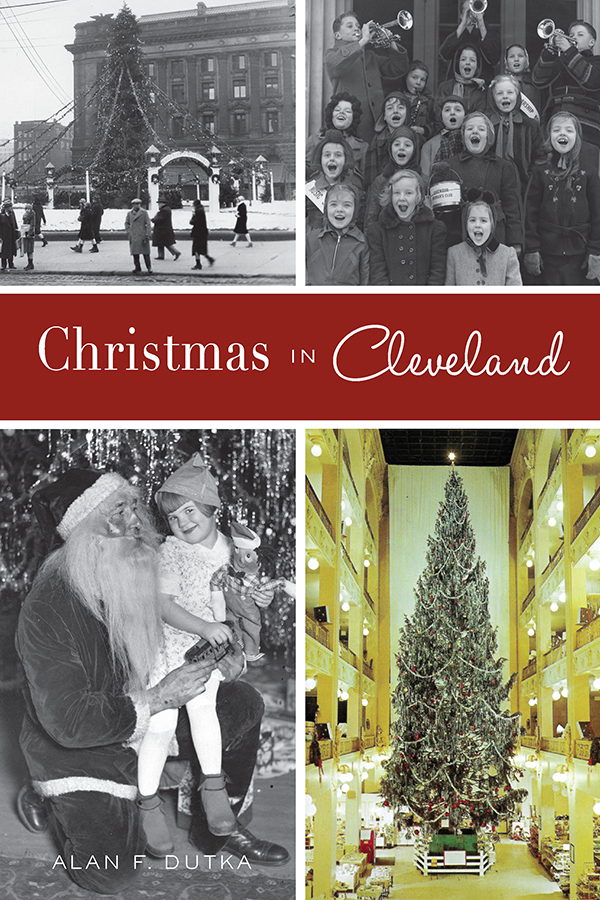

I was born and raised in Cleveland at the proper age to vividly recall the glorious department store Christmas windows, lights on Public Square and gigantic Sterling-Lindner-Davis Christmas trees. But I must have grown up much too fast or spent too much time in an alternate universe because viewing the Sterling trees never seemed to be as fun as feasting on a sirloin steak or a hamburger, followed by a hot fudge sundae, in a downtown restaurant. Shopping with my mother at the age of six, I was amused by the animated Christmas windows at the Halle department store for no more than two minutes. Viewing the Stillman Theaters marquee across the street, I suggested to Mom that, since she must have been pretty tired having already reaching the advanced age of forty-three, maybe we could rest while watching The Three Musketeers. I had never heard of either Lana Turner or Gene Kelly, but as she was a fan of both, I got my wish.

My most vivid Christmas memory occurred on December 25, 1959, when I spent about ten hours downtown laboring in the dark. As an usher at the Stillman Theater, I toiled from noon until 10:00 p.m., with one thirty-minute break to grab a hamburger and milkshake at LaMars Restaurant across the street in the CAC Building. The line to purchase tickets that Christmas day started at 11:00 a.m. and didnt end until the box office closed at 10:00 p.m. Thanks to full-page advertisements in the Plain Dealer every Sunday from Thanksgiving to Christmas, along with radio and television commercials, the opening of the biblical epic Solomon and Sheba produced the second-largest moneymaking day in the history of the theater.

After conducting research for this book, I cant believe that I was so indifferent toward the wonders of celebrating Christmas in Cleveland. For all of you who had a better appreciation for the holiday season, or if you would like to learn more about what you missed due to age or apathy, here is my best attempt at re-creating Clevelands holiday seasons starting as far back as the earliest pioneers.

Acknowledgements

Members of three different departments at the Cleveland Public Library contributed to this book: photographs (Brian Meggitt and Adam Jaenke), history (Olivia Hoge, Terry Metter, Danilo Milich, Lisa Sanchez and Aimee Lepelley) and special collections (Stacie Brisker and Bill Chase).

At Cleveland State University, William C. Barrow in special collections and Vern L. Morrison made contributions in obtaining images and providing insights.

Saint John Cathedral, the Cleveland Ballet, the City Ballet of Cleveland and Great Lakes Theater provided beautiful images, as did M.O. Ghorbanzadeh. Priscilla Dutka, once again, provided her amazing proofreading skills and special insights.

Lastly, I would like to thank John Rodrigue and Ashley Hill from The History Press.

Introduction

Christian missionaries considered Clevelands first settlers heathens because of their lack of interest in Christmas. Yet today, magnificent churches enhance the landscapes of almost every Cleveland neighborhood.

As early as 1881, Clevelands department stores displayed Christmas merchandise and decorations on the Friday following Thanksgiving. Eighty years later, in 1961, readers of the Plain Dealer conveyed their extreme dissatisfaction with rushing the season when stores exhibited Christmas decorations a week prior to Thanksgiving:

Two weeks before Christmas should be enough time for decorating and really getting into the swing of things.

My husband and I are doing our own private boycotting by not mentioning Christmas until after Thanksgiving and refusing to allow our children to listen to TV Christmas shows.

Starting this early to think, speak and display Christmas is a punishment to children; to make them aware of Christmas so far ahead is a cruelty beyond the realm of human dignity.

Many of the enclosed malls that were so instrumental in ending downtowns once near monopoly on Christmas shopping have been demolished. Most of the great downtown department store buildings remain in existence, but they are no longer shopping meccas. The structures that were once home to the Taylor and May Companies now accommodate luxury apartments. The Halle edifice is a combination apartment and office building. The Higbee department store building is now a casino with office space on the higher floors. A portion of the Sterling-Lindner-Davis complex is an office building; another segment houses a parking lot. The Bailey site is a multistory parking garage with a ground-floor restaurant.

Today, many Clevelanders prefer laptop computers to radios and record players for enjoying Christmas music. Social media and email have diminished the importance of the post office in delivering holiday greetings. The giant downtown movie screens have been superseded by downloading and streaming alternatives. The internet is challenging the importance of brick-and-mortar stores for Christmas shopping supremacy. Yet through decades of change, Clevelanders still worship in church services, gather for family dinners, attend holiday stage productions and relish giving and receiving holiday presents. Beginning with Clevelands first settlers, Christmas in Cleveland surveys the local holiday scene through two hundred years of remarkable excitement and change.

Celebrating the Season

Clevelands pioneers expressed little interest in celebrating Christmas; in fact, many held holiday merriment in downright disdain. Clearing towering trees, constructing makeshift log cabins and plowing and cultivating what they hoped would become fertile farmland didnt stimulate gaiety and laughter. Life-threatening encounters with four-foot-long venomous rattlesnakes, four-hundred-pound black bears, packs of wolves, wandering wildcats, two-hundred-pound panthers and herds of wild hogs did nothing to improve their predicament. Even so, early Clevelanders relished the boisterous Fourth of July celebrations they initiated shortly after arriving in the pristine territory. The pioneers aversion to Christmas festivities stemmed mostly from a firmly established disapproval of the idea of the holiday itself.

Thomas Robbins, an early missionary in Northeast Ohio, described the settlers as being openly hostile toward religion. Pioneer Moses White hesitated to expose his wife to a territory that had acquired a reputation for being a heathen land and Godless community. Yet the most devout Christians also ignored Christmas celebrations. The Puritan American contempt for extolling Christs birth dates back to Plymouth, Massachusetts. Even prior to a Puritan-led Parliament outlawing Christmas celebrations in England, the Plymouth pilgrims demonstrated their disapproval of Christmas festivities by purposely engaging in hard work on their first December 25 in the New World. William Bradford, the colonys governor, once chastised a group of boys for engaging in playful games on Christmas Day and presented a clear directive: Work or go to jail.

Next page