IMAGES

of America

CHICAGOS

LOST LS

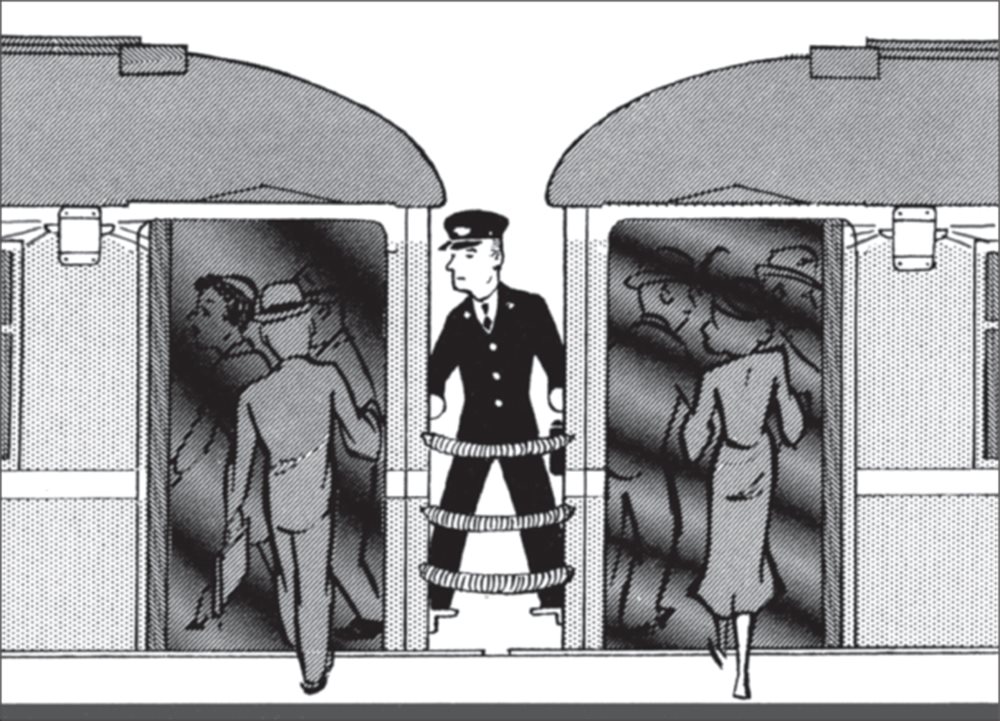

Before 1950, there were no married pairs of L cars in Chicago. Trains could be as small as a single car. A three-car train required two conductors whose jobs were to open the passenger entry doors (which were on the sides at the ends of the cars) using controls situated between the cars. To operate his side doors, a conductor had to stand between the carsin any weather. Conductors told the motorman when to proceed and had to observe when the doors were clear. A bell system was used to notify the motorman. Two dings meant proceed, and one ding meant hold. The rearmost conductor started with his bell, then the next rearmost, and so on, until two dings rang in the motormans compartment, which was his signal to go. The longer the train, the longer it took to leave the station. The New York elevated had multiple unit door controls in the 1920s, but after the Depression, the Chicago L lacked money to install them, even though it would have saved on labor costs. (Authors collection.)

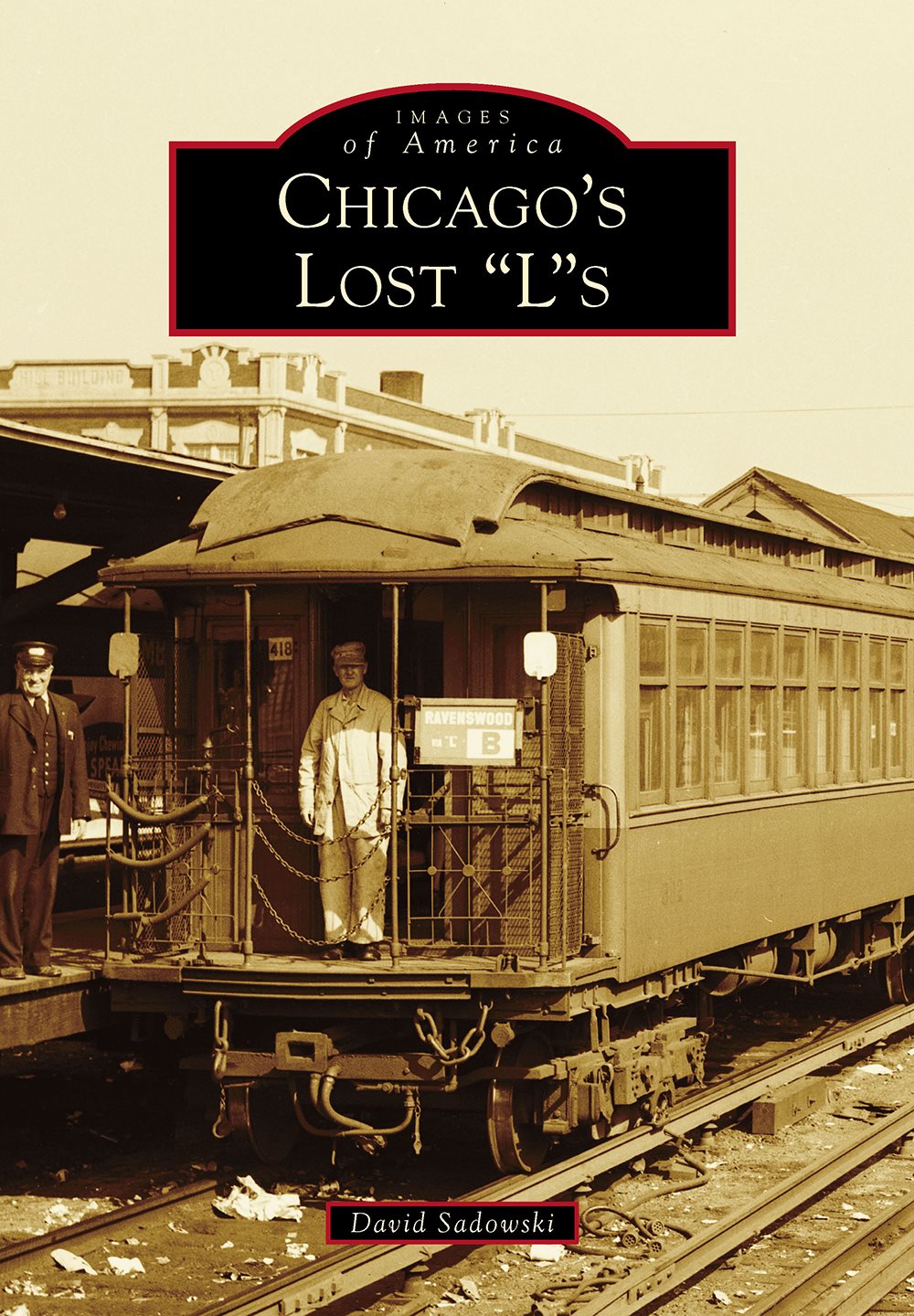

ON THE COVER: In this 1950 photograph, Chicago Transit Authority motormen and conductors prepare to depart the Ravenswood L terminal at Kimball and Lawrence Avenues in the Albany Park neighborhood on Chicagos northwest side. L car No. 392 was built in 1905 by the American Car & Foundry Company for the South Side L. It was retired in 1957. (Authors collection.)

IMAGES

of America

CHICAGOS

LOST LS

David Sadowski

Copyright 2021 by David Sadowski

ISBN 978-1-4671-0602-3

Ebook ISBN 978-1-4396-7291-4

Published by Arcadia Publishing

Charleston, South Carolina

Printed in the United States of America

Library of Congress Control Number: 2020947748

For all general information, please contact Arcadia Publishing:

Telephone 843-853-2070

Fax 843-853-0044

E-mail

For customer service and orders:

Toll-Free 1-888-313-2665

Visit us on the Internet at www.arcadiapublishing.com

To Raymond DeGroote Jr., the dean of Chicago railfans

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The author wishes to thank the following individuals, without whose assistance this book would not have been possible: Jack Bejna, Craig Berndt, Glen Brewer, Eric Bronsky, Leslie Engelberg, Graham Garfield, Ross Harano, David Harrison, the late John Horachek, Diana L. Koester, Andre Kristopans, Bruce C. Nelson, Don Ross, J.J. Sedelmaier, William Shapotkin, John Smatlak, David Stanley, George Trapp, and the late Jeffrey L. Wien. Special thanks go out to my editors Stacia Bannerman and Ryan Vied, who helped make this a better book.

The references used in the course of completing this work include:

Chicagos Metropolitan Elevated Railway. Leslies Weekly. June 6, 1895: 386.

Dana, William B., ed. Street Railway Supplement of the Commercial & Financial Chronicle, March 9, 1895. New York: William B. Dana Company, 1895.

Davies, Owen, ed. Chicago Elevated Railroads Consolidation of Operations, 1913 (reprint). Chicago: Owen Davies, 1967.

Mass Transportation in Chicago Moves Forward. Mass Transportation. January 1939: 510.

Running on the L. Chicago Daily Tribune. June 7, 1892: 9.

The West Side Metropolitan Elevated Railway System of Chicago. Scientific American. April 27, 1895: 264.

For further reading, check out the authors transit blog at www.thetrolleydodger.com.

Unless otherwise noted, all images are from the authors collection.

Note: Chicagos street numbering system, which has been in use since the early 1900s, is in the form of a grid, with State Street being the eastwest coordinate and Madison Street the northsouth. The numbers provided in parentheses after many of the street names will help readers orient themselves to various locations. For example, there are eight blocks in a mile throughout most of the city, so Western Avenue, which is three miles west of State Street, is written as 2400 W.

INTRODUCTION

Chicago became the fastest growing city in the world as it rose from the ashes of the disastrous 1871 fire. It quickly grew to a size where public transit became a necessity. First came the omnibus, horsecar, cable car, andfinallythe electric streetcar. The streets were congested, and gridlock ensued, especially downtown. New York inventors came up with the idea of elevated railways that would defeat traffic by rising above it. Starting in 1868, the New York El gradually caught on, and by the 1880s, there were several lines in Manhattan. Chicago began to take notice. Elevated railways were no fly-by-night undertaking. They required major capital and held the promise of major profits.

Numerous companies were formed to construct elevated railways in Chicago, but only four succeededthe South Side Rapid Transit Railroad Company (1892), Lake Street Elevated Railroad (1893), Metropolitan West Side Elevated (1895), and Northwestern Elevated Railroad (1900). Chicagos south side was more developed than the north and west sides (there is only a small east side, far to the south due to the shape of Lake Michigan), and that is where the first L (as Chicagoans refer to it) was built.

When Chicago was chosen by Congress to host the Worlds Columbian Exposition in 1890, the city had to get serious with building the Ls in a hurry. The 1893 worlds fair also spurred a grade-separation movement in Chicago. Many existing railroads were put on embankments between 1890 and 1910. The Ls were part of that movement. The South Side L began service on June 6, 1892, and was an immediate success. It was colloquially known as the Alley L, since its original route to Thirty-ninth Street ran next to an alleyway, even though it was built on private property. Like the New York Ls, it used small steam engines to pull unpowered coaches. The L was extended to Jackson Park, site of the worlds fair, the following year. At the exposition, visitors were transported by the experimental Columbian Intramural Railway, which was powered by electricity. By the end of 1893, the Lake Street L had started running to the west side. Soon, service reached as far west as suburban Oak Park, again powered by steam.

The Metropolitan West Side Elevated opened on May 6, 1895, and was innovative in several respects. First, it used electricity from the start. Second, it was planned with several branch lines, and third, it had four tracks near the downtown area, facilitating express trains in addition to locals. Fourth, it had adequate yards and shops, mostly at the ends of lines. These were important advantages over the other Ls, which eventually were retrofitted with a third track for express trains over parts of their lines; at times, it was difficult to find adequate storage space for trains. All three Ls suffered from the same probleminadequate distribution downtown. Their stubend terminals were all located on the outskirts and therefore limited their appeal. High start-up costs led to bankruptcies, reorganizations, and corporate name changes.

Enter Charles Tyson Yerkes (18371905), often called the Robber Baron of Chicago transit. Yerkes controlled several street railways on the north and west sides. He saw the new Ls as both a threat and an opportunity, and he seized the moment. First, he took over the Lake Street L. Next, he had a brilliant ideaa downtown Union Loop (known as the Loop) that would solve the distribution problem faced by all the Ls. They would all benefit, but obtaining the necessary permissions from businesses and the city was a complex and difficult undertaking. Fortunately, Yerkes was up to the task. The Lake Street L line was extended east to Wabash Avenue, putting one fourth of the Loop in place. Once it had this advantage, the South Side L pressed for an extension, which became the Wabash leg in 1896.

Next page