Copyright 1976 by The University Press of Kentucky

Scholarly publisher for the Commonwealth,

serving Bellarmine University, Berea College, Centre

College of Kentucky, Eastern Kentucky University,

The Filson Historical Society, Georgetown College,

Kentucky Historical Society, Kentucky State University,

Morehead State University, Murray State University,

Northern Kentucky University, Transylvania University,

University of Kentucky, University of Louisville,

and Western Kentucky University.

All rights reserved.

Editorial and Sales Offices: The University Press of Kentucky

663 South Limestone Street, Lexington, Kentucky 40508-4008

www.kentuckypress.com

Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available from the Library of Congress.

ISBN 978-0-8131-0140-8 (pbk: acid-free paper)

This book is printed on acid-free recycled paper meeting

the requirements of the American National Standard

for Permanence in Paper for Printed Library Materials.

Manufactured in the United States of America.

| Member of the Association of

American University Presses |

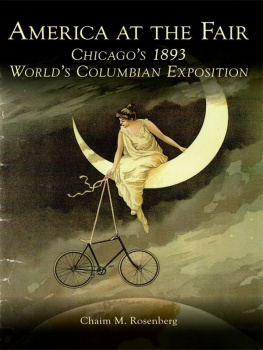

PREFACE

THE WHITE CITY was the most popular title of that most remarkable event, the Worlds Columbian Exposition, otherwise known as the Chicago Worlds Fair of 1893. The White Citys life was brief but legendary. It inspired hundreds of publicationscatalogs, photographic albums, speeches, essays, novels. It was the subject of four full-length histories and a fifth unfinished one which alone consist of thousands of pages. A merely cursory investigation reveals that the Worlds Columbian Exposition evoked far more commentary than any exposition in history. Obviously this study cannot do justice to all that commentary. But from the written records it gleans the important outlines of the story and the meaning of the exposition. In addition to the plethora of commentary published in its own time, the exposition has been referred to since by numerous social, architectural, and intellectual historians. It has been sometimes extravagantly praised; more often, resoundingly damned. Whether laudatory or damnatory, however, historians have generally conceded that the exposition was an event of genuine cultural import. Even so, retrospectively, no attempt has been made to evaluate that import in a study of sufficient length to do justice to the subject. This study makes the attempt.

It is not enough to assume merely on the basis of voluminous accumulated commentaries that the White City deserves the attempt. Consequently, one purpose of this study is to argue the expositions historic merit. There are several reasons why such a study rewards interest. One is the nature of the event itself. International expositions are of recent origin. The first was the Great Exhibition held in London in 1851 which was the scene of Joseph Paxtons Crystal Palacethe first large-scale, prefabricated iron and glass buildingwhich alone attested that fairs significance. From then until 1893 there were several European expositions, probably the most famous being that held in Paris in 1889, celebrated for its Eiffel Tower. The United States had hosted several trade fairs but only one full-scale international exposition, that held in Philadelphia in 1876, the celebration of the centennial of American independence. The Worlds Columbian Exposition would be the fifteenth worlds fair and the second American one. But it was of vastly greater scope than any of its predecessors. Early expositions had consisted simply of one large exhibition hall, as at the Great Exhibition, or of such a hall augmented with attached or nearby sheds. The main hall might be artfully designed, but little attempt was made to lay out the surrounding grounds or to embellish the buildings with sculpture and paintings. The Paris Exhibition of 1867 originated both the idea of gridlike layouts for buildings and a park site plan. By the time of the 1889 Paris Exhibition many buildings, such as the Trocadero, were permanent, as successive expositions there were always held at the Champs de Mars. It was the 1889 exhibition that inspired the Worlds Columbian Exposition. But the progeny far surpassed its forebears. Paris, London, Vienna temporarily transformed their appearances to host their expositions. Chicago created a veritable new city. That city was not only larger than any previous exposition but also more elaborately designed, more precisely laid out, more fully realized, more prophetic. First of all, this was to be a celebration of the four hundredth anniversary of Columbuss discovery of the New World, of which the United States was only a part, though, as the Americans assumed, the greatest part. Given the historic setting, it would have been inconceivable that a Latin American country would have hosted the event. It was intended from the start, however, to be a genuinely international exposition. That is, it was the first exposition truly to solicit the participation of the entire world. Hence in an era of intense nationalistic rivalries and imperialistic ambitions, the Worlds Columbian Exposition reflected a unique spirit of internationalism.

Another and more important reason for studying the exposition is the fact that the White City was intended to inform all visitors of the momentous achievements in such areas as fine arts, industry, technology, and agriculture of the United States, the first new nation, in Seymour Martin Lipsets phrase, whose political, cultural, and economic endeavors had prepared her to join the ranks of the worlds great nations. In short, the exposition was a celebration of Americas coming of agea grand rite of passage. It was also the primary representative event of an era that Henry Steele Commager has aptly designated as the watershed of American history. On the one side lies an America predominantly agricultural; concerned with domestic problems; conforming, intellectually at least, to the political, economic, and moral principles inherited from the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.... On the other side lies the modern America, predominantly urban and industrial; inextricably involved in world economy and politics... ; experiencing profound changes in population, social institutions, economy, and technology; and trying to accommodate its traditional institutions and habits of thought to conditions new and in part alien. Thus Commager referred to the entire decade of the 1890s as the historic divide between past and present America. Though an early event of the nineties, the exposition embodied and portended that truth. The Worlds Columbian Exposition was both hail and farewell.

It is therefore instructive of how Americans saw themselves in a period of profound and complex change. The extraordinary responsiveness of visitors, both informed critics and lay public, to the wonders of the White City is highly revealing of American values, anticipations, and aspirations. The making of the exposition, as an achievement of cooperative endeavor and technical expertise and as a singular agglomeration of inventive and exotic amusements, is a story of high culture and popular culture combined. It is a story of masterful artistic and engineering achievement. The creation of the White City provided a giant index of an urban-industrial environment that might have been, had the publics enthusiastic regard been honored; had the vicissitudes of rapid change, commercial enterprise, and political priorities developed differently. As such the fair is an incomparable event in American history. It demonstrated at a timely juncture that the artistic capacity and technical knowledge were available to transform new industrial cities into well-designed centers of business, culture, and humane community in agreeable combination. For the White City was in itself such a well-designed center.