Copyright 2011 by Mary Soames

All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Random House, an imprint of The Random House Publishing Group, a division of Random House, Inc., New York.

R ANDOM H OUSE and colophon are registered trademarks of Random House, Inc.

Originally published in Great Britain by Doubleday, an imprint of Transworld Publishers, a Random House Group Company, in 2011.

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Soames, Mary.

A daughters tale: the memoir of Winston Churchills youngest child / by Mary Soames.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references.

eISBN: 978-0-679-64518-4

1. Soames, MaryChildhood and youth. 2. Churchill, Winston,

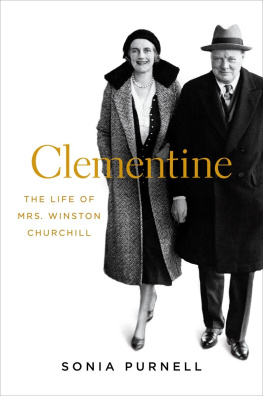

18741965. 3. Churchill, Clementine, Lady, 18851977.

4. Soames, MaryFamily. 5. Great BritainHistory

George VI, 19361952. 6. World War, 19391945Great Britain.

7. Great BritainBiography. I. Title.

DA566.9.S57A3 2012 941.084092dc23 2011037070

[B]

www.atrandom.com

246897531

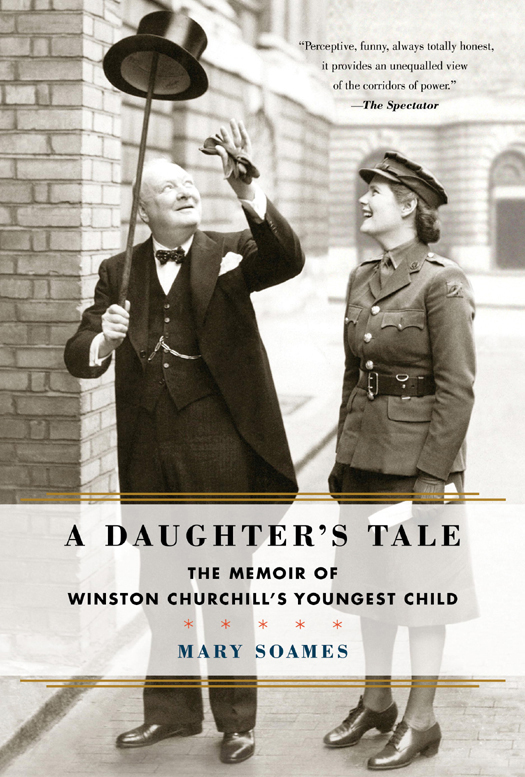

Jacket design: Kimberly Glyder

Front-jacket photograph: Getty Images

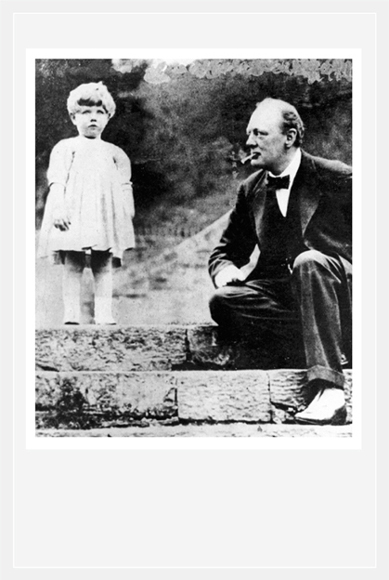

Back-jacket photographs: Mary Soames Collection (top left and top right); Churchill Archives Centre,

The Papers of Randolph Churchill, RDCH [9/2/4B], reproduced with permission of Curtis Brown, London,

on behalf of The Estate of Randolph S. Churchill, copyright

Randolph S. Churchill (inset, top); Daily Mail/Rex Features (center); AP/Press Association Images

v3.1

Note on Sources

T HE TEXT QUOTES EXTENSIVELY FROM THE AUTHORS PERSONAL diaries, which remain in her possession, as do letters from the author to her parents. Letters from Winston Churchill up to his resignation in July 1945 are held in the Chartwell Papers, Churchill Archives Centre, Churchill College, Cambridge. Letters from Clementine Churchill are held in the Baroness SpencerChurchill Papers, also in the Churchill Archives Centre, Churchill College, Cambridge. Papers in these collections are not cited individually in the endnotes.

The authors letter to David Lloyd George, 20 September 1937, is held in the Lloyd George Papers, Parliamentary Archives, Westminster. The authors letter to W. Averell Harriman, 13 May 1941, is held in the Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.

Prelude

A S THE 1920S BEGAN, CONDITIONS SEEMED SET FAIR, PROFESSIONALLY and personally, for Winston Churchill and his family. From the summer of 1917, when Winston had returned to office as Minister of Munitions after the debacle of the 1915 Dardanelles campaign had cost him his place in Asquiths Coalition government, he had served in various ministries and permutations of Lloyd Georges Coalition governments, and in early 1921 he was appointed Secretary of State for the Colonies. Winston was in his forty-seventh year and Clementine, whom he had married in 1908, ten years younger: their family consisted of Diana, aged twelve years; Randolph, ten; Sarah, seven; and Marigold, rising three.

But 1921 was to be a year of heavy tidings for the Churchill family. In early January, Blanche, the redoubtable Countess of Airlie, died. Clementine had never been really fond of her grandmother, but her death brought back memories of childhood summer holidays at Airlie Castle with her so dearly beloved sister Kitty (who had died aged only sixteen), and the twins, Nellie and Bill. Later that month the death in a railway accident of a distant Londonderry kinsman of Winstons, Lord Herbert Vane-Tempest, brought shock and regret if not grief; his unexpected demise wrought changes in Winstons fortunes, the consequences of which belong to a later chapter.

Then, in the spring, stark tragedy struck. In April, Bill Hozier, Clementines only brother, aged thirty-three, shot himself in a hotel bedroom in Paris. And at the end of May, Lady Randolph Churchill, the beautiful and celebrated Jenniein predictably high heelsfell down a staircase: a month later, after amputation of her leg, and a sudden haemorrhage, she died, in her sixty-eighth year. She had become a legend in her own lifetime, and her death was widely mourned. Her sons, Winston and Jack, grieved deeply; and if their wives, Clementine and Goonie, had had their reservations in the past about Belle Ma-mans extravagances and vagaries, the undaunted spirit with which she met the difficulties in her life, and her great courage in her last weeks, commanded their true and loving admiration.

A quieter departure was the death in early August of Thomas Walden, who had been Lord Randolphs manservant: he had accompanied Winston to the South African war, enlisting in the Imperial Light Horse, and continued in service with him after the war. He was indeed a family treasure, and his departure was a cause of great sadness for Winston.

But the worst blow in this already dark year was yet to come. Winston and Clementines youngest child, Marigold, had been born four days after the Armistice in 1918. A chubby, redheaded, lively baby, the Duckadilly was the pet of the family. Reading her parents letters to each other during Marigolds brief infancy, one perceives from passing references that she was markedly prone to sore throats and catching colds, so probably earlier action should have been taken when the child developed symptoms while in seaside lodgings, along with Diana, Randolph, and Sarah, at Broadstairs in Kent in early August. The nursery party, in the charge of a young French nanny, Mlle. Rose, was due to travel north to join Winston and Clementine for a lovely family holiday in Scotland, staying with the Duke and Duchess of Westminster: but the plan collapsed when Marigold became ill, with what developed rapidly into septicaemia of the throat. Tragically, the nanny failed to recognize the seriousness of the childs condition, and it was only after prompting by the lodging-house landlady that Clementine was sent for. She rushed immediately to Broadstairs, to be joined shortly by Winston, and a London specialist was sent forbut alas, to no avail: the adored Duckadilly died with her distraught parents at her side on the evening of 23 August. She was two years and nine months old.

Many years later my father told me that when Marigold died, Clementine gave a succession of wild shrieks like an animal in mortal pain. My mother never got over Marigolds death, and her very existence was a forbidden subject in the family: Clementine battened down her grief and marched on. I was about twelve, I think, when I asked my mother who was the tubby little girl wearing a sun hat and holding a spade in the small photograph on her bedroom deskand she told me: the picture had been taken on the beach at Broadstairs a week or two before Marigolds death. But it was many more years before I discovered that my mother regularly visited the pathetic little grave in the vastness of a London cemetery, with its beautiful memorial cross by Eric Gill: she never invited me to accompany her. It was only during our many conversations at the time when I was beginning work on her biographythis was in the 1960sthat she at last brought herself to open up to me about Marigold.