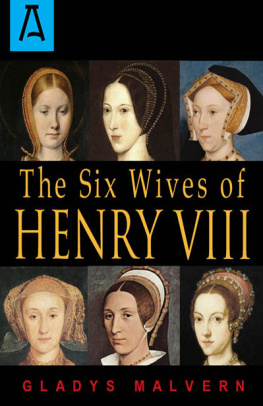

T he Six Wives of Henry VIII is one of the worlds great stories: indeed, it contains a whole world of literature within itself. It is more far-fetched than any soap opera; as sexy and violent as any tabloid; and darker and more disturbing than the legend of Bluebeard. It is both a great love story and a supreme political thriller.

It also has an incomparable cast of characters, with a male lead who begins as Prince Charming and ends as a Bloated Monster with a face like a Humpty-Dumpty of Nightmare. While, among the women (at least as conventionally told), there is almost the full range of female stereotypes: the Saint, the Schemer, the Doormat, the Dim Fat Girl, the Sexy Teenager and the Bluestocking.

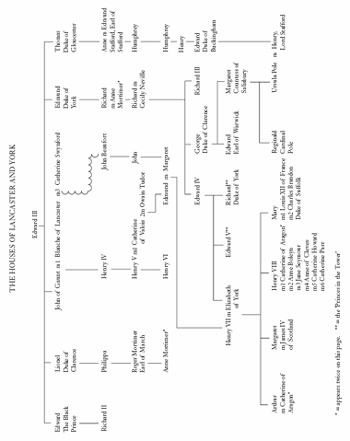

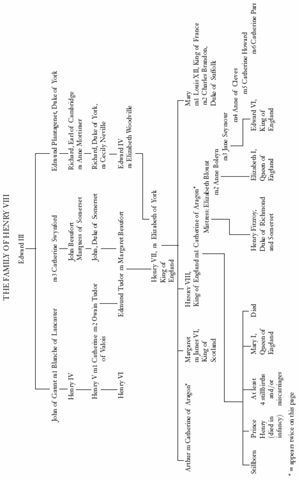

Finally, it evokes, like the best historical novels, the peculiarities of the behaviour and mind-set of another agethe quirks of sixteenth-century etiquette and love-making; the intricacies and passions of religious faith and practice; the finer points of heraldry, genealogy and precedence; the gleaming stiffness of cloth of gold and the unclean roughness of the hair shirt. But it also touches the timeless universals of love and honour and betrayal and death.

What is strangest of all, it is true.

And, being true, it is supremely important. For the reign of Henry VIII is a turning point in English history second only to the Norman conquest. When he came to the throne, Henry was the Pious Prince who ruled an England at the heart of Catholic Europe; when he died, he was the Great Schismatic, who had created a National Church and an insular politics that shaped the development of England for the next half a millennium.

Once, historianswho imagined that England was somehow naturally Protestantthought there were profound social and religious reasons for the change. It is now clear there were none. Instead, it came about only because Henry loved Anne Boleyn and could get her no other way. And he stuck to what he had done, partly because it tickled his vanity, but also because no succeeding wife was able to persuade him out of it.

It is, of course, a story that has often been told before. It was given its classic shape as long ago as the nineteenth century by Agnes Strickland in her immensely influential Lives of the Queens of England. Within this vast work, the number and importance of the Queens of Henry VIII made them, as Strickland herself recognised, virtually a book within a book. Stricklands historical discoveries were equally important. She used all available printed sources. She charmed (she was very pretty, especially for a scholar) her way into the national archives of both Britain and France. And, unlike the male historians of her time and long after, she realised the importance of cultural history and made effective use of buildings, paintings, literature and the history of manners.

The result was that she invented, more or less single-handedly, the female biographer as a distinctive literary figure, and established the lives of women as a proper literary subject.

It is a formidable achievement. But there is almost as great a drawback to Stricklands work. For she was undiscriminating and credulous and, as a true daughter of the Romantic Era, loved a legendthe more sentimental and doom-laden the better. Such stuff seeps through her pages like a virus. Like a virus, it risks corrupting the whole. And, like a virus again, it has proved almost impossible to get rid ofwith consequences that linger to the present.

Everyone knows, for instance, that Catherine Parr, Henrys last Queen, acted as nurse to her increasingly lame and sickly royal husband. But there is no mention of this fact in the earlier, classic characterisations of the Queen. Herbert in the seventeenth century focuses on her ageshe had some maturity of yearsand Burnet in the eighteenth on her religionshe was a secret favourer of the Reformation. But neither mentions her supposed nursing skills. The first to do so, indeed, seems to be Strickland herself, who paints a bold and vivid picture of Catherine as a Tudor Florence Nightingale. She was the most patient and skilful of nurses, Strickland claims, and she shrank not from any office, however humble, whereby she could afford mitigation to the sufferings of her royal husband. It is recorded of her, Strickland continues, warming to her theme, that she would remain for hours on her knees beside him, applying fomentations and other palliatives to his ulcerated leg.1

But curiously, despite the claim to evidential support, Strickland cites no sources. And, in fact, there are none. Instead, the idea of Catherine as her husbands nurse is a fiction and rests on a wholly anachronistic view of the relations of sixteenth-century Kings and Queens. Henry had male doctors, surgeons, apothecaries and body servants. There was no need for his wife to act as nurse. Indeed the notion would have been regarded as absurd, even indecent.

But that has not stopped modern historians. To a man and a woman, they have repeated Strickland, and they have sought to go one better by finding evidence. Their search has turned up the accounts of Catherines apothecary for 1543. These indeed note innumerable fomentations and palliatives. But they were all for Catherine herself or for members of her Household. Henrys name, however, despite the explicit assertion of Neville Williams, does not appear.2

Stricklands power is therefore considerable: it turns assertion into fact and makes respectable scholars see things.

Inevitably, the twentieth-century versions of the Six Wives have stood in Stricklands shadow. Martin Hume, The Wives of Henry VIII (1905), was a self-consciously masculine reaction, which emphasised the political at the expense of the personal. But both Alison Weir, The Six Wives of Henry VIII (1991), and Antonia Fraser, The Six Wives of Henry VIII (1992), despite their considerable merits, reverted to Stricklands tried-and-tested formula.

Nor was this book intended to be any more ambitious. I had a few new points to make. But I thought I could fit them into a short, vivid retelling of the familiar story.

It was only once I began work that I realised I had to start from scratch. For, as I wrote, the conventional story started to come apart in my hands. The result is the present book: which is both very big (which my publishers have come to love) and very late (which gave them many a headache).

My problems started quickly, with the character of Henrys first wife, Catherine of Aragon. Catherine is one of Stricklands less satisfactory lives. This is largely a question of materials. Or rather a lack of them, since the archives of Spain, unlike those of Britain and France, remained firmly closed to her. And yet there were riches there. Gaining access to them in their dusty fastness at Simancas made the name of the Victorian historian, James Anthony Froude. But it was only with the publication of the Calendar of Letters, Despatches and State PapersPreserved in the Archives at Simancas and Elsewhere that the treasures were made generally and comprehensively available. Historians promptly fell on them and all subsequent assessment of Catherine has been based on the evidence of the Calendar .