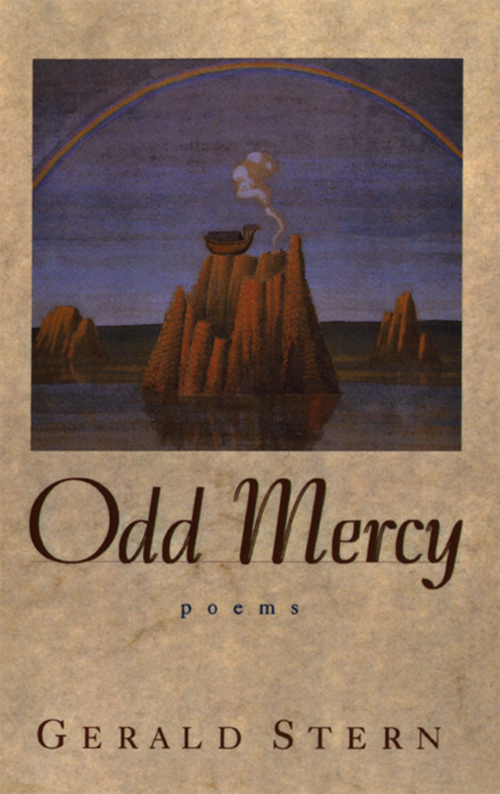

Some of these poems have been published in the following magazines and journals: American Poetry Review: Birthday, Hinglish, Hot Dog Black Warrior Review: Diary Colorado Review: Odd Mercy Exquisite Corpse: Love Me, The Sorrows Field: Only Elegy Kenyon Review: Ida The New Yorker: St. Marks, Most of My Life Poetry: Did I Say, Light, Mimi TriQuarterly: Blacker than Ever Ducks Are for Our Happiness, Birthday, and Bitter Thoughts were published in the Bread Loaf Anthology of Nature Poetry; The Jew and the Rooster Are One was published in Transforming Vision: Writers on Art (Edward Hirsch, editor); and Blue was published in a special collection of poems on painters in the Iowa Museum of Art (Jone Graham, editor). Oracle and Essay on Rime appeared in Cutbank Spring 1995, along with an interview. ALSO BY GERALD STERN Bread Without Sugar Leaving Another Kingdom: Selected Poems Two Long Poems Lovesick Paradise Poems The Red Coal Lucky Life Rejoicings

Some of these poems have been published in the following magazines and journals: American Poetry Review: Birthday, Hinglish, Hot Dog Black Warrior Review: Diary Colorado Review: Odd Mercy Exquisite Corpse: Love Me, The Sorrows Field: Only Elegy Kenyon Review: Ida The New Yorker: St. Marks, Most of My Life Poetry: Did I Say, Light, Mimi TriQuarterly: Blacker than Ever Ducks Are for Our Happiness, Birthday, and Bitter Thoughts were published in the Bread Loaf Anthology of Nature Poetry; The Jew and the Rooster Are One was published in Transforming Vision: Writers on Art (Edward Hirsch, editor); and Blue was published in a special collection of poems on painters in the Iowa Museum of Art (Jone Graham, editor). Oracle and Essay on Rime appeared in Cutbank Spring 1995, along with an interview. ALSO BY GERALD STERN Bread Without Sugar Leaving Another Kingdom: Selected Poems Two Long Poems Lovesick Paradise Poems The Red Coal Lucky Life Rejoicings  Gerald Stern is the author of eight previous collections of poetry. He is the winner of a number of grants, prizes, and awards; the most recent are the 1996 Ruth Lilly Poetry Prize and (with John Ashbery) the 1996 best poem award from The American Poetry Review. He lives in Easton, Pennsylvania, and New York City.

Gerald Stern is the author of eight previous collections of poetry. He is the winner of a number of grants, prizes, and awards; the most recent are the 1996 Ruth Lilly Poetry Prize and (with John Ashbery) the 1996 best poem award from The American Poetry Review. He lives in Easton, Pennsylvania, and New York City.

Copyright 1995 by Gerald Stern All rights reserved First Edition The Library of Congress has cataloged the printed edition as follows: Stem, Gerald, 1925 Odd mercy : poems I Gerald Stem. p. cm. I. Title. W. W.

Norton & Company, Inc., 500 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10110 W. W. Norton & Company Ltd., Castle House, 75/76 Wells Street, London W1T 3QT T he centerpiece of Gerald Sterns ninth collection is a long poem entitled Hot Dog, named for a beautiful street woman who lives in and around Tompkins Square Park in New York. Other characters in the poem are St. Augustine, Walt Whitman, Noah, Gerald Stern himself, and a ninety-year-old black preacher from the Midwest.

In Hot Dog and throughout, Stern wrestles with the issueshope, memory, faiththat have always occupied him. It is that they spend so much time in the sky that bluebirds have streaks of red across their chests; and it is thatexcept for the robbing of their houses they came north for my birthday bringing the light of southern Texas with them. Every year I am able to do the mathematics and stand like another birdoutside my door with one foot in and one foot out, half-looking for the first light and whisper one phrase or other one or the otherand look for a streak of red and a flash of blue. If you asked me what I lived for Id say it was for knowledge; Id never say I was waiting to see the sun come up behind the willow; or Id say I was living to see the bluebirds come east again; Id never say I was waiting for justice, or I was waiting for vengeance and recovery; Id say I was waiting to see the thumbnail moon at five oclock in the evening, or I was waiting to see what shape it takes by morning or when it becomes an acorn moon. Id never say the bluebird has disappeared from the east, the starling has driven him out; Id never turn to the starling and the English sparrow and hate them for their stubbornness how could I as a Jew?Id never say the pigeon is our greatest pest; how could I who came from New York City myself? Id say its too late to go to Idaho and sight the distance to the pole; Id say Ill never move now to southern Arizona-Id let the forest come back to Pennsylvania. I am half-English when it comes to trees; I live for the past as much as the futurewhy should I lie? I am ruined by the past.

I can trace my eyelids back to central Asia. It is when the thaw comes and the birds begin to swell with confusion and a few wild seeds take hold and the light explodes a little I lie down a second time, either to feel the sun or hear the house shake from the roar of engines at the end of my street, the train from North Dakota carrying sweeteners to Illinois, moving forward a single foot, then backwards another, one of those dreary mysteries, hours of shrieking and banging, endless coupling, the perfect noise to go with my birthday, grief and grinding enough, wisdom enough, some lily or other growing on the right-of-way, some brakeman still wearing a suit from Oshkosh, he and I singing a union song from 1920, some dead opossum singing something about a paw-paw tree, his hands over his eyes, some bluebird greased with corn oil and dreaming of New York State singing songs about the ruins or about the exile, notes from southern Texas, notes from eastern Poland, drifting into the roundhouse, Lamentations of 1992, a soft slurring on her part, a tender rasping on mine, though both of us loving the smell of mud, I think, and both of us willing to snap some twigs, although for different reasons I think, and both of us loving light above all else, almost a craving that occupied our minds in late February and made us forget the darkness and the wobbling between two worlds that overwhelmed us only a month or two before. It has to be the oldest craving of all, the first mercy. I kick a piece of leather; except for the claw its mostly sky. Let the silkweed bury it and let the silkweed bury the silkweed. There isnt a particle of life there, thats if leather can have a life.

Silkweed sends its seed to cover the bodythere is grease; there are feathers on the claw. Juice, I think, juice of the cat, juice of the silkweed. The pods are empty, there is no cream, only a little white left over, dry and fluffy. Let the nail bury the nail, let the helmet of someone named Knute bury the helmet of someone named Si or Cyrus. Inside the bliss is gone, the mind is empty; it has moved from one form of grasping to another. I lift it up, it is a kind of football, something between a dry tongue and a ball.

I execute a perfect dropkick, claw after clawthere still are dropkicks in Pennsylvania. It could be the self growing more aloof that gives me the courage, something I can hide behind. I still freeze when I see a corpse, the spiteful dead imitating the living, still lying there with a hand between their thighs, or a paw lifted up against the light. Let the clogged-up neck bury the clogged-up neck, let the wristbone bury the wristbone. If there is someone named Si let there be someone named Cyrus, let him run like Knute ran. In my thirteenth and fourteenth year I spent my afternoons at the Schenley Oval running until it got dark.

I was alone on the ancient track.Was it a mile and a quarter? I know the empty stands were still intact the way they were when horses rounded the bend. The palings were even intact. Let the dark boy with the long face come and stand at the railing, let him comb his hair, the part on the left, let him wipe away the sweat, then look at the moon while he waits for his father; he will spend his lifetime waiting. If there is a brown seed on his shoulder, if it came from the plant beside the fence, it is almost lighter than life and came by air to land as the current decided. He reaches for a twig and breaks it off, the pods are perfect, they are like round canoes with graceful prows and ribbing that holds the silk together. He had vertigo from running, he thoughtsometimes he stopped on a sidewalk or under a tree to feel itit was the pleasure he kept to himself.

I still have that pleasure. Who is the football, he or I? Who is the cat? Am I or he? The son of man, what is that in the other writing? He has neither a Sears nor a Posturepedic. Let me be the father and bury myself. Follow me. We are sitting on wooden boxes. We are singing without lungs! Let the sea horse bury the sea horse, let him die standing up.

Next page

Some of these poems have been published in the following magazines and journals: American Poetry Review: Birthday, Hinglish, Hot Dog Black Warrior Review: Diary Colorado Review: Odd Mercy Exquisite Corpse: Love Me, The Sorrows Field: Only Elegy Kenyon Review: Ida The New Yorker: St. Marks, Most of My Life Poetry: Did I Say, Light, Mimi TriQuarterly: Blacker than Ever Ducks Are for Our Happiness, Birthday, and Bitter Thoughts were published in the Bread Loaf Anthology of Nature Poetry; The Jew and the Rooster Are One was published in Transforming Vision: Writers on Art (Edward Hirsch, editor); and Blue was published in a special collection of poems on painters in the Iowa Museum of Art (Jone Graham, editor). Oracle and Essay on Rime appeared in Cutbank Spring 1995, along with an interview. ALSO BY GERALD STERN Bread Without Sugar Leaving Another Kingdom: Selected Poems Two Long Poems Lovesick Paradise Poems The Red Coal Lucky Life Rejoicings

Some of these poems have been published in the following magazines and journals: American Poetry Review: Birthday, Hinglish, Hot Dog Black Warrior Review: Diary Colorado Review: Odd Mercy Exquisite Corpse: Love Me, The Sorrows Field: Only Elegy Kenyon Review: Ida The New Yorker: St. Marks, Most of My Life Poetry: Did I Say, Light, Mimi TriQuarterly: Blacker than Ever Ducks Are for Our Happiness, Birthday, and Bitter Thoughts were published in the Bread Loaf Anthology of Nature Poetry; The Jew and the Rooster Are One was published in Transforming Vision: Writers on Art (Edward Hirsch, editor); and Blue was published in a special collection of poems on painters in the Iowa Museum of Art (Jone Graham, editor). Oracle and Essay on Rime appeared in Cutbank Spring 1995, along with an interview. ALSO BY GERALD STERN Bread Without Sugar Leaving Another Kingdom: Selected Poems Two Long Poems Lovesick Paradise Poems The Red Coal Lucky Life Rejoicings  Gerald Stern is the author of eight previous collections of poetry. He is the winner of a number of grants, prizes, and awards; the most recent are the 1996 Ruth Lilly Poetry Prize and (with John Ashbery) the 1996 best poem award from The American Poetry Review. He lives in Easton, Pennsylvania, and New York City.

Gerald Stern is the author of eight previous collections of poetry. He is the winner of a number of grants, prizes, and awards; the most recent are the 1996 Ruth Lilly Poetry Prize and (with John Ashbery) the 1996 best poem award from The American Poetry Review. He lives in Easton, Pennsylvania, and New York City.