Copyright 2020 by Guy Stern. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced without formal permission. Manufactured in the United States of America.

ISBN: 978-0-8143-4759-1 (jacketed cloth)

ISBN: 978-0-8143-4760-7 (ebook)

Library of Congress Cataloging Number: 2019957276

Wayne State University Press

Leonard N. Simons Building

4809 Woodward Avenue

Detroit, Michigan 482011309

Visit us online at wsupress.wayne.edu

The excerpt on is from Hilde Domin, Vorsichtshalber. In: Smtliche Gedichte. S. Fischer Verlag GmbH, Frankfurt am Main 2009. By courtesy of S. Fischer Verlag GmbH, Frankfurt am Main.

To my wife, Susanna Piontek, beloved companion in life, sage advisor, and fellow writer

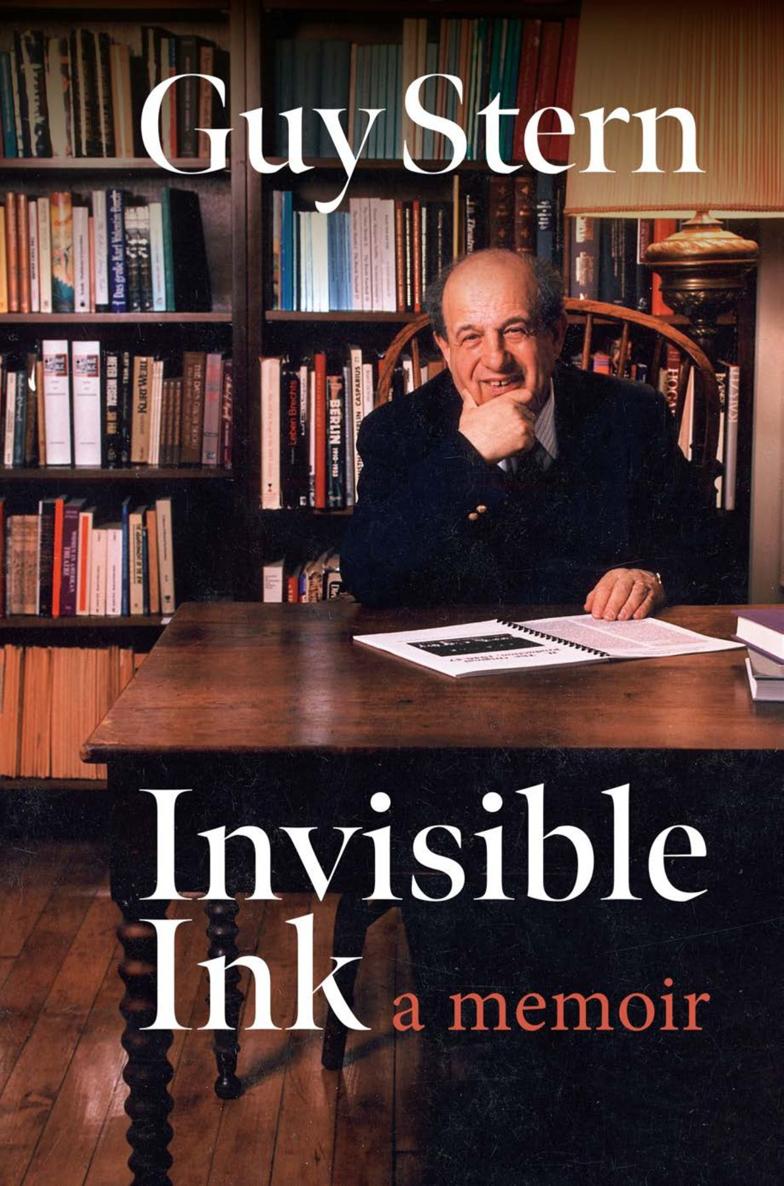

Invisible Ink

A fter I finished the irrevocably last sentence of this autobiography, I started searching for an appropriate title. Three different ones seemed to be worth exploring. One of these described a series of events that recurred throughout my life and invariably changed its course. Few of these events could have been foreseen. I called them chance encounters and for a while I thought my book would bear that title.

Here are some of the events that made the label so compelling to describe the roller-coaster ride of my life. Chance encounters abound, with strangers emerging at various turning points. At fifteen years of age, my life was saved because of a brief meeting with a kind United States consular official. My family perished because of a half-hour encounter with a hapless, hidebound local attorney in St. Louis, who thwarted their rescue. After World War II, my postwar plans were sent helter-skelter. A rare meeting with one of my superior officers, a senior editor of the New York Times, sent me scurrying off to New York. One short telephone call led to my discovery of the whereabouts of a long-lost cousin.

I found my present wife because she had been pressured at the last minute into attending a public lecture of mine. I unearthed a hitherto unknown branch of my wifes family by taking a wrong turn during a nocturnal walk in a small Swiss town near Locarno. Finally, while writing this autobiography, some of my wartime experiences came rushing back to me because of a chance encounter with a British gentleman, a one-time resident of Bristol. That led me back in minute detail to those all-engrossing weeks, when we had been planning the most gigantic invasion of enemy-held territory in human history. Contrary to Einsteins observation, God (or fate) may play dice after all.

Another idea was to call these recollections Of Life, Loss, Love, and Literature, for its euphonious alliteration and beyond. Love was lavished upon me by many people who walked alongside me during my long and variegated life. For all too brief a time, it was primarily given to me by my family. My losses can be summarized by the word Holocaust and the untimely deaths of my son, Mark, and my wife, Judy. As to literature, my immersion in books started in my childhood and accompanied me all throughout my career as a professor of literature and is still clinging to me even beyond retirement. Language has been my lifes passion and my life preserver. The ability to use persuasive language was my intermittent ally at dangerous moments throughout my life. For example, as a dean in the 1960s, I squelched an escalating students riot via an impassioned appeal to reason. Earlier, in 1937, I stood before an American consular official, pleading for a visa to the sheltering shores of the United States. Fifteen years old at the time, I stammered forth the right answers to his questions in acceptable English, received the appropriate US stamp and seal on my papers, and was thereby spared the fate of my parents, grandmother, brother, and sisterall victims of the Nazi Holocaust.

Throughout everything that has happened to me, language has been my mainstay and muse, my labor and leisure, lodestar and love. New words have always fascinated me; as a kid I soaked them up like a sponge and sometimes shattered the composure of the adults by my mature vocabulary. Owners of cigar stores in Hildesheim (where I grew up), whom we kids pestered for collectible pictures for our albums, ranging from postcard-like views of German cities to models of automobiles, usually shooed my playmates and fellow collectors unceremoniously out of their stores. But often they gave me a hearing, I suspect because my precocious eloquence entertained them, and some of the coveted cards of automobiles, animals, national flags, and city sites landed in my collection.

Two sources fed my insatiable appetite for delectable tidbits of language. There was my wildly indiscriminate reading, ranging from spurious Wild West stories to watered-down German classics. But even more important and enduring were the conversations with my mother. My German, then and now, comes from my motheror rather my mothers tongue. She was a luminous woman who had an unerring instinct for just the right word. She was, amid our far-flung family, the occasional lyric poet. For my Bar Mitzvah she put together a multipage album of poems, in which she gently spoofed the foibles of twenty-one Bar Mitzvah dinner guests. Nor did she spare me: Zigarrentabak schmeckt auch aus der Pfeife (You can savor cigar leaves smoked from a pipe). I had dismembered one of my fathers cigars, intended for customers, and had ignited the leaves in a clay pipe from a toy set.

My own attempt at humor was more boisterous. It came about because of my one and only and quite shameful encounter with foreigners. Come to think of it, we Hildesheimers were a bit provincial and xenophobic. One day when I was fourteen, I encountered two young French ladies, smartly dressed, with their faces stylishly made up. They were crossing the square in front of the Cathedral of Saint Andrew. A sizable group of youngsters and adults was following them like the satellites to the orbiting planets. Not having seen ladies with make-up before, we outdid ourselves with witty, nay, absurd, remarks. I offered the ladies the use of my watercolor box. While recalling this bit of juvenile fatuity, my face turns redder than the rouge on the faces of those two poor French women. Only one year later, I and my fellow Jews became the targets of verbal insults. But my penchant for language on that occasion was served. One of the French women responded with an expression I had not heard in my beginning French class in high school. Ta gueule, she said to me. As I fled the plaza commemorating the saintly Andrew, it dawned on me that I was told to shut up in no uncertain terms. I was taken aback, of course, but then felt triumphant that I had acquired an expression that would have been banished from our French class.

When I reached the age of fourteen, my parents took me along to adult plays performed at our local theater. I can still reconstruct isolated scenes, for example, from a drama called Uncle Braesig. I remember mostly the protagonists intermittent pratfalls, when least expected, and his inane, funny expletive, hurled repeatedly at a friend. Why, just keep your nose in your face! I didnt understand why this remark made the audience convulse with laughter. But there may have been something in the context or the acting that was suggestive beyond the comprehension of this fourteen-year-old.