BOOKS BY

Joseph Wechsberg

BLUE TROUT

AND BLACK TRUFFLES

1953

THE

CONTINENTAL TOUCH

1948

SWEET AND SOUR

1948

HOMECOMING

1946

LOOKING

FOR A BLUEBIRD

1945

Published by

Academy Chicago Publishers

363 West Erie Street

Chicago, Illinois 60610

First printing 1985

Second printing 2001

Copyright 1948, 1949, 1951, 1952, 1953

by Joseph Wechsberg

Printed and bound in the U.S.A.

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced

in any form without the express written

permission of the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Wechsberg, Joseph, 1907

Blue trout and black truffles.

Reprint: Originally published: New York: Knopf, 1954.

1. Restaurants, lunch rooms, etc.France.

2. Wine and wine makingFrance. I. Title.

TX910.F8W37 1985 647.9544 85-3847

ISBN 0-89733-134-6

T HE AUTHOR S THANKS are hereby made to the following magazines in which several of the chapters of this book originally appeared in somewhat different form: To The Atlantic for Provence without Garlic; to Cosmopolitan for The Ladies from Maxims; to Gourmet for Tafelspitz for the Hofrat and A Dish for Lucullus; to Holiday for Black Truffles, The Mysterious Fish Soup, and Worth Special Journey; and to The New Yorker for A Balatoni Fogas to Start With, Connoisseurs and Patriots, and The Finest Butter and Lots of Time.

CONTENTS

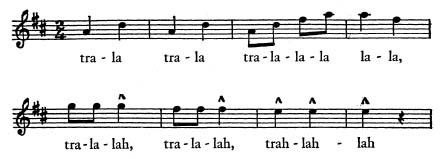

SEVENTEENTH-CENTURY BURGUNDY WINE SONG

Someday hell want to eat more than hes going to get.

DR. HIMMELBLAU

MY DELICATE CHILDHOOD,

OR: THE EDUCATION OF A GOURMET

N OWADAYS I travel hundreds of miles and dont mind crossing international boundaries to lunch at one of my favorite restaurants, but I wasnt always like that.

As a child, I used to run away from food. I would chew on a bite of meat and refuse to swallow until my mother promised to let me go to the cinema. When I was a first-grader in Ostrava, my home town in Moravia, I would get sick every morning at the sight of my breakfast.

The grown-ups said I was a delicate, nervous child, oversensitive and afraid of school. They were wrong. I didnt mind schooluntil the ten oclock recess. Then the boys and girls would unpack their sandwiches and hard-boiled eggs, and I would turn green in the face and get sick again. I couldnt stand the smell of food.

In these years I was kept alive on a diet of frankfurters and cocoa. I had to be tricked into swallowing frankfurters and cocoa in odd moments of mental bemusement. Other foods had to be camouflaged to look and taste like frankfurters or cocoa before I would touch them. It might have been easier to feed me intravenously. I was a spoiled brat, but thats hindsight, of course.

People on the street would stop my mother and inquire about my sallow face. They said I must be quite ill, poor boy. My mother would start to cry. She had the ability to laugh and cry in the same breath, but in those days I rarely made her laugh.

Marie, our old cook, and Fraulein Gertrud, the governess, proffered various suggestions to break the deadlock of my stomach. They thought I should take long walks in the fresh air, or go to the mountains or to the sea. Sometimes they said I needed a good spanking.

Luckily, my father had no confidence in such amateurish suggestions. He knew that there was nothing wrong with me; the women just didnt handle me intelligently. To prove his point, he would take me out on Sunday mornings. We would get on the streetcar for Svinov, a dreary factory suburb, and for two hours we would ride back and forth. My father bribed the motorman to let me push my foot down on the bell; sometimes I was permitted to turn the wheel of the mechanical brake. The streetcar began to jolt and the people inside would berate the motorman; once there was a fight and a policeman had to be summoned. In wintertime it was cold on the motormans platform, but my father would stand next to me, and he didnt mind the cold. He seemed to enjoy the ride.

Afterward we would walk over to the Konditorei Wollgart, the best confectionery in town. I was still elated from driving the streetcar, and the sight of chocolate-coated Indianer, cakes, patisserie, Sachertorte with whipped cream wasnt repulsive at all. I would eat a couple of Indianer dreaming of a bright future when I was going to drive a streetcar all by myself.

When we came home, the air was filled with the aroma of the Sunday dinner. My face would turn green.

My father told my mother about the Indianer. The boy would eat everything if you women would only treat him right, he would say.

The soup was served. I got sick. Small wonder, my mother said, acidly. After all that stuff Id eaten at the Konditorei.

When I had one of my fits of prolonged starvation, refusing even frankfurters and cocoa, my father would call up Dr. Himmelblau, the family physician.

When I had one of my fits of prolonged starvation, refusing even frankfurters and cocoa, my father would call up Dr. Himmelblau, the family physician.

Anything serious? Dr. Himmelblau would ask. Ill be right over.

We-ll, my father would say, cautiously. He was a man of quiet dignity and he couldnt tell a lie. Hehe doesnt want to eat.

Oh, Dr. Himmelblau would say. II have to see a few patients. But Ill drop in tonight. He didnt consider me a patient.

Dr. Himmelblaus polished bald head was like a much-used billiard ball from any angle you looked at it. Throughout all the years his appearance never changed. Even in his sixties he had the timeless appearance of a slightly underfed Chinese Buddha.

He professed no concern whatsoever at my lack of appetite. Sometimes he would glance perfunctorily at my outstretched tongue, perhaps to please my anxious parents, but later on he wouldnt even do that. Fortunately, Dr. Himmelblau was thoroughly impervious to the theories of Professor Doctor Sigmund Freud, though Vienna, and Dr. Freud, were only a few hours by train from my home town. I hate to think what some of Dr. Freuds disciples would do to me today if I refused to eat anything but frankfurters and cocoa.

Once Dr. Himmelblau gave me a thoughtful look and said to my parents: He will be all right. Someday hell want to eat more than hes going to get. It was a remarkable blend of accurate diagnosis and correct prognosis.

A few months afterward I caught a cold, undernourished and transparent as I was, and came down with pneumonia and pleurisy. He almost died, my mother later said. She would break into tears at the very memory of my sickness.

A few months afterward I caught a cold, undernourished and transparent as I was, and came down with pneumonia and pleurisy. He almost died, my mother later said. She would break into tears at the very memory of my sickness.

When I felt better, Dr. Himmelblau advised my parents to take me to a famous professor in Vienna for a checkup. The professor, an internist, lived in the ninth district, practically within stethoscope range from Dr. Freud. He knocked all over my frail body, listened to the windpipes inside my chest, and pronounced that only the southern sun would heal me.

Next page

When I had one of my fits of prolonged starvation, refusing even frankfurters and cocoa, my father would call up Dr. Himmelblau, the family physician.

When I had one of my fits of prolonged starvation, refusing even frankfurters and cocoa, my father would call up Dr. Himmelblau, the family physician.