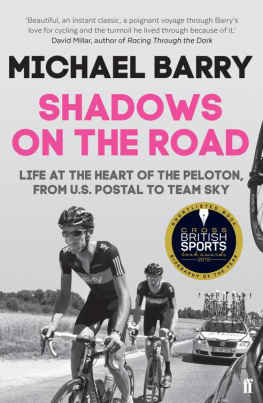

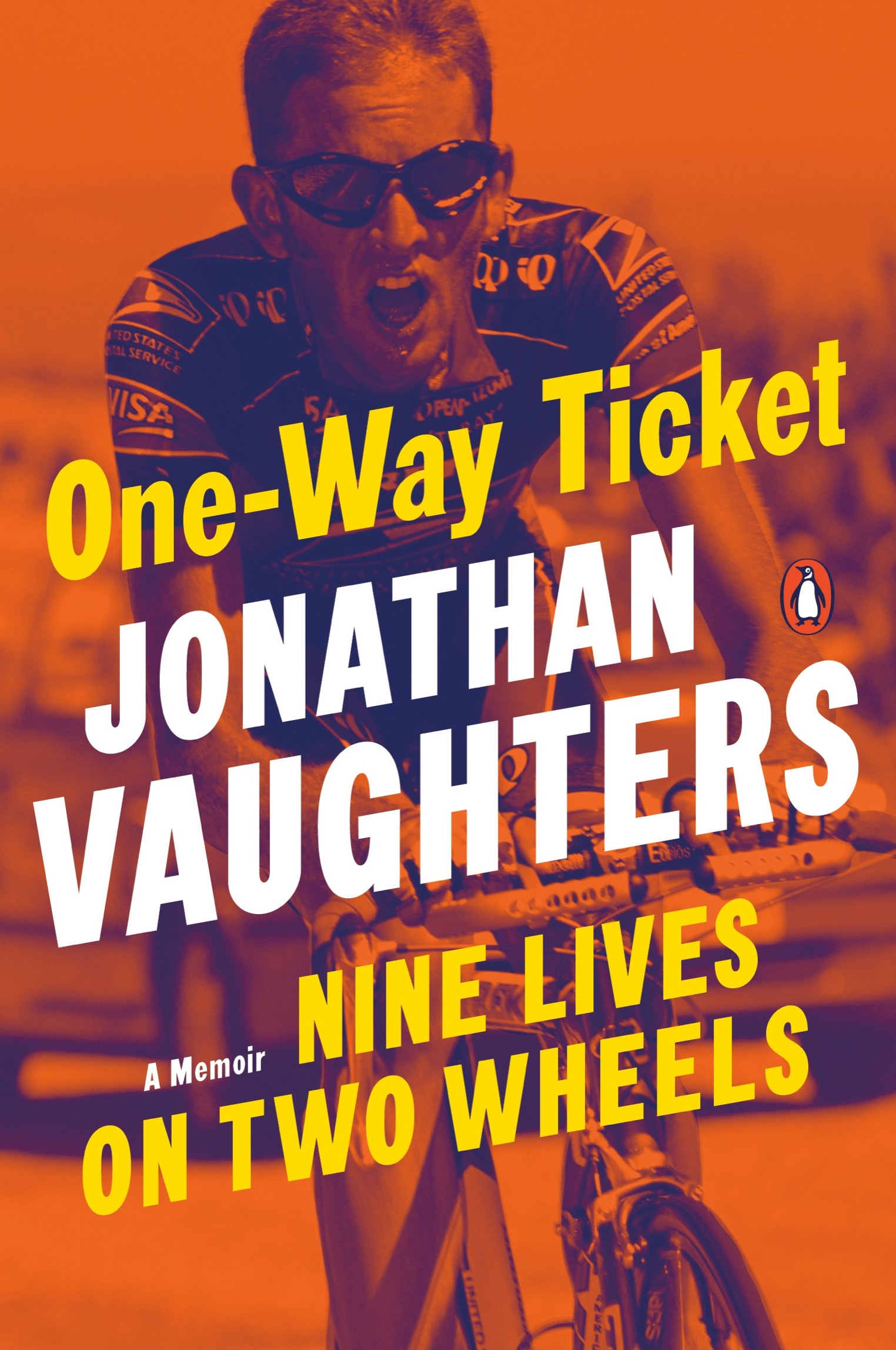

I started bike racing in complete ignorance of the fact that, from its early days, the sport had been tainted by cheating in many forms. By the time I retired from racing, I knew all about it. It is hard to pinpoint the moment when my innocence was broken, as it was a realization that slowly dawned on me rather than a single moment when I suddenly knew. I imagine the same is true for anyone involved in the sport in the 1990s and early 2000s. Enough riders have failed drugs tests, and enough have admitted to having doped, that no one can deny that the sport was thoroughly infected by doping in one form or another for many years. That is not to say that everyone did it, or that everyone knew at the time, and nothing in this book should be taken as indicating guilt on the part of anyone who has not already been found guilty of, or confessed to, illegal use of banned materials.

All I will say is that, considering how rife doping was, anyone who succeeded in the sport without doping deserves to be hailed as honorable and exceptional. Instead, sadly, everyone involved in the professional sport of road cycling during that era has the cloud of suspicion hanging over them. One of the reasons I wrote this book is to acknowledge the part I played in the creation of that cloud, and to document the things I have done since in an effort to make amends.

PROLOGUE

One of the first things youll see, heading west from my parents house at the top of a hill in suburban Denver, is the enormous outcrop of Mount Evans.

Every ride to school in my dads orange Volvo station wagon, and every training ride I ever did as a child, started with me staring straight up at this huge mountain.

Its an imposing and beautiful view to see every day. It gave me purpose, gave me motivation, and even as a kid, filled my heart with the spirit of the high mountains.

Its a gorgeous mountain to look at from the top of that little hill by Mom and Dads house. In winter, its a massive snow-covered giant staring back at you. In the summer, it embodies the purple mountain majesties of Katharine Lee Batess song America the Beautiful.

At 14,265 feet tall, it is one of Colorados highest mountains, and very much the most visible from the city of Denver. What makes it special, particularly to bike racers, is that it has a paved road all the way to the top. Its the highest paved road in North America, and one of the highest paved roads in the world.

Every kid in Colorado whos ever raced a bike dreams about winning the legendary race up Mount Evans. But the lure of the race isnt just about winning, but also about setting the record up the Old Lady. For a cycling-mad teenager, owning the record up Mount Evans is like holding the key to immortality.

At 14,000 feet, nature moves fast, and if you want the record, God needs to smile on you. The winds must be just right, the weather just stable enough. To set the record you have to never let up on the pace, yet also keep a close eye on your competition, as they may sit behind you on the shallow gradients, waiting to win and unconcerned with the record.

Bob Cook, a Colorado native and peer to three-time Tour de France winner Greg LeMond, was not only a world-class cyclist, but was also a world-class academic and engineer. Bob won the Mount Evans hill climb time after time in the 1970s and 1980s, but then, just after graduating from university, was diagnosed with a brain tumor and passed away. From there on, the race was named the Bob Cook Memorial.

I won on Mount Evans for the first time as a fourteen-year-old. It was a technical victory, as I was racing with older kids and finished fifth, but the four kids in front of me were all seventeen or eighteen years old. Our race only went halfway to the top, so we got to watch as the professional riders came past on their trudge upward into the thin, rarefied air.

I so wanted to be one of them. I thought that maybe Bob Cook was my spirit mentor. I wanted to be just like him.

I became absolutely obsessed with Mount Evans after that victory. I wanted to become one of the legends to conquer that mountain. I wanted to be king. That was how I started a fifteen-year journey of trying to break the record up Mount Evans.

The record became my Moby Dick, reminding me of Ahab and anguish... stretched together in one hammock.

I chased it to the point of insanity. Many times, when it easily should have been mine, somehow it would slip away. After failing, I would stare at that mountain all year waiting for another chance to claim the record.

I drilled holes in my bike, sought out a lighter option for every component on the bike, tried experimental diets, spent weeks at extremely high-altitude training. Now, in 2019, thats all standard stuff. However, in the early 90s, it was seen as lunacy and obsessive. Indeed, I was obsessed.

My first real crack at the record was in 1992. The year before, as a seventeen-year-old, Id finished fifth in the professional race, so I figured with a year more of adolescent growth under my belt, Id be ready to compete for the win. I asked my team to be let out of the normal race schedule so that I could go and train in Leadville, at 10,000 feet. They begrudgingly granted me permission to go and become a crazed hermit in the old mining town for a month.

I trained harder than I ever had and adopted a low-carbohydrate diet in pursuit of losing a few pounds. I risked getting kicked off my team by replacing all the sponsor-friendly parts on my bike with the absolute lightest components I could find.