ALSO BY BARBARA GOLDSMITH

The Straw Man

THIS IS A BORZOI BOOK

PUBLISHED BY ALFRED A. KNOPF, INC.

Copyright 1980 by Barbara Goldsmith

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by Alfred A. Knopf, Inc., New York, and simultaneously in Canada by Random House of Canada, Limited, Toronto. Distributed by Random House, Inc., New York.

Grateful acknowledgment is made to the following for permission to reprint excerpts from previously published material:

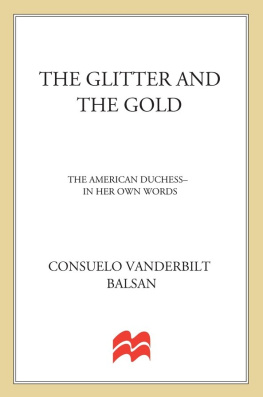

Doubleday & Company, Inc.: Excerpts from GERTRUDE VANDERBILT WHITNEY : A BIOGRAPHY by B. H. Friedman, with Flora Irving. Copyright 1978 by B. H. Friedman. Reprinted by permission of Doubleday & Company, Inc.

David McKay Co., Inc.: Excerpts from DOUBLE EXPOSURE : A TWIN AUTOBIOGRAPHY by Gloria Vanderbilt and Thelma Furness. Copyright 1958 by Gloria Vanderbilt and Thelma Furness. Reprinted by permission of David McKay Co., Inc.

Warner Bros. Music and Chappell & Co. Ltd.: Excerpt from lyrics of ANYTHING GOES by Cole Porter. 1934 Warner Bros. Inc. Copyright Renewed. All Rights Reserved. Used by Permission.

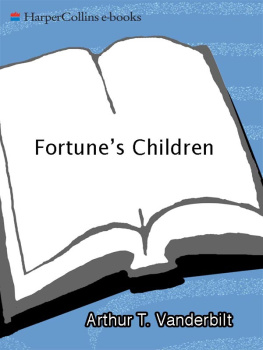

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING IN PUBLICATION DATA

Goldsmith, Barbara.

Little Gloria happy at last.

Bibliography: p.

1. Vanderbilt, Gloria, 1924- 2. ArtistsUnited StatesBiography. I. Title.

N6537.v33G64 1980 700.924 [B] 79-3483

eISBN: 978-0-307-80032-9

v3.1

For these women

my mother, Evelyn

my sister, Ann

my daughter, Alice

Contents

Introduction

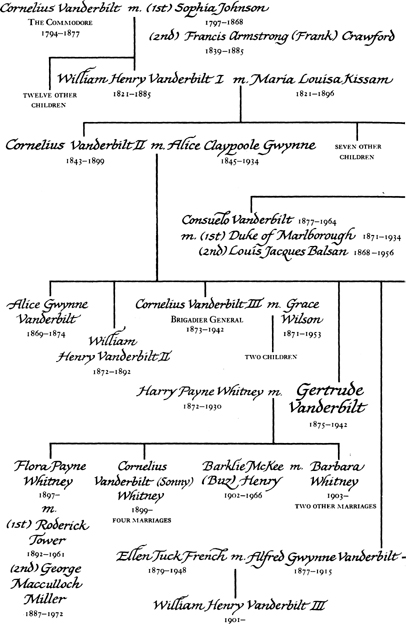

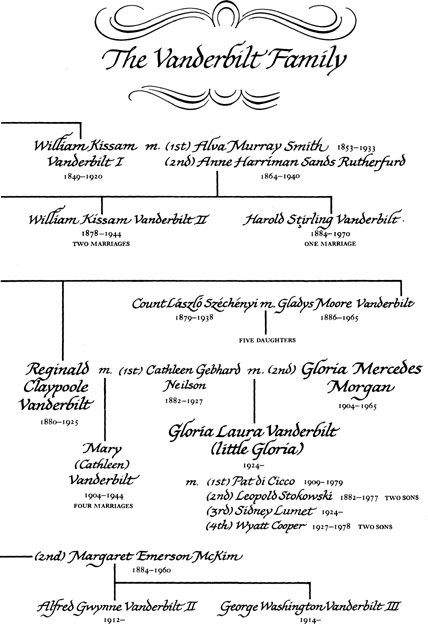

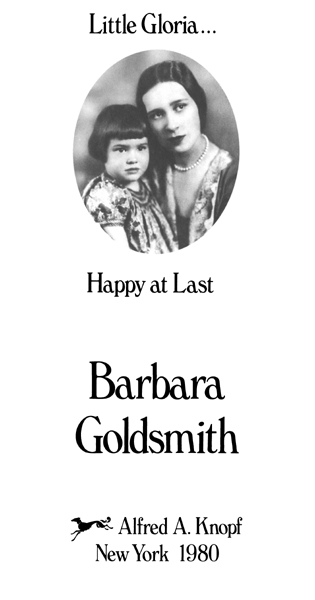

T HE Matter of Vanderbilt was the most sensational custody trial in the history of the United States. It exploded into headlines on the first day of October 1934, and didnt leave the front pages of newspapers across the country until the year was out. The sensation lay in the clash of wills between two internationally famous women, Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney and her sister-in-law Gloria Morgan Vanderbilt, over the custody of solemn, ten-and-a-half-year-old Gloria Laura Vanderbilt. At the time of the trial, Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney was known as the richest woman in America. She was seen by the press as a haughty austere matriarch, the bearer of two mighty social names, the owner of vast estates, a mother and grandmother, a sculptor and art patron, founder of the Whitney Museum of American Art. Gloria Morgan Vanderbilt was a famous international beauty, a widow still in her twenties who was to be seen frolicking in the most fashionable places and who numbered among her friends the most impressive titles in Europe.

This trial took place during the Great Depressiona time when bright dreams had been shattered, and poverty, misery, hunger, and disillusionment were the order of the dayand a glamour-starved public eagerly consumed the accusations against Gloria Morgan Vanderbilt involving a German prince, a member of the British royal family, and an adulterous relationship with a flamboyant, married, playboy-businessman, a Jew and therefore automatically barred from the Society world of the Whitneys and Vanderbilts. Gloria Morgan Vanderbilt found herself accused of neglecting her child while she danced till dawn, of drinking alcohol, of reading pornography, of total indifference to her childs welfare, and of one thing more that so shocked the judge that he cleared the courtroom and conducted the rest of the trial in secrecya secrecy he was powerless to maintain.

Then there was the child herself, whom the press snatched up and immediately designated The Poor Little Rich Girl. Here was a perfect Depression symbol, a gold child, a Vanderbilt heiress worth millions who was dressed in rags, lonely, sick, neglected. These people might be rich, but they seemed emotionally impoverished, with no love to give. It was a consoling thought that this little girl, for all her money, seemed worse off than the poorest Depression child. And this was a time when children had become extraordinarily important as symbols of hope and optimism. At that moment, life held only misery and frustration, but children represented a limitless, untarnished future in which things would surely come right. People responded passionately to Little Orphan Annies smile and optimism, to Shirley Temples bobbing bright curls, to the phenomenon of the Dionne quintuplets in their temperature-controlled nursery behind their one-way glass.

For the entire last quarter of 1934, the Matter of Vanderbilt shared the spotlight with another trialthe extradition proceedings against Bruno Richard Hauptmann, the alleged kidnapper-murderer of the infant son of Colonel Charles Augustus Lindbergh. There was a hidden link between these two proceedings, but no one connected them at the time. At the center of the Matter of Vanderbilt was a mystery: during the trial one questionthe crucial oneremained unanswered. No one could adequately explain little Glorias hysterical, bizarre behavior. Clearly, the child was frightened to death, but no one could discover the root of her fearnot her mother, not her nurse (who had never left her for a single day in her life), not her grandmother, not her Aunt Ger (Gertrude Whitney), not a battery of competent doctors and lawyers, all of whom had questioned her. But I believe I discovered it.

Not immediatelyat first, reading little Glorias testimony in the voluminous trial transcript, I realized only that I was feeling edgy and uneasy; threatened, really. Certain phrases she had used sparked my earliest memories. I was afraid she would take me awaydo something to me then IT would happen. Reading and rereading little Glorias testimony, a secret language that I knew from my own childhood flooded back on me. I felt I knew exactly what she was saying. And I knew what IT was. She was speaking the language of kidnapping, and IT was death.

It came as a shock to me that I could understand something that all the people surrounding little Gloria had not understood (for if they had, the entire notorious and damaging trial might never have taken place); and I realized that I possessed this basic, emotional knowledge because, like little Gloria, I had been a child while The Crime of the Century was unfolding. (Had I been born even a few years earlier or later, I might have been as mystified by little Glorias behavior as everyone else was.) I too had experiencedas a childthe terrible force of the Lindbergh case. It was a crime that shocked the world, but it held a special significance for children. From the moment the baby son of Americas greatest hero was snatched from his crib (on the night of March 1, 1932), terror came rushing into American homes. If this could happen to so exalted a personage, then who was safe? In fact, from 1930 to 1932 there had been more than two thousand kidnappings in America, but this one was to become the quintessential American kidnapping, and later, many people would incorrectly assume that it had also been the first.

It was not the first, but it was the one that put fear into the hearts of a generation of children; little Gloria Vanderbilt knew about the Lindbergh kidnapping and so did I. I could recite the details like a litany. The kidnapper put a ladder up to the second-story nursery window. It was dark when he took the baby from his crib. His mommy and daddy were in the house and so was his nanny, but someone got him anyway. His daddy paid the kidnapper a lot of moneybut it didnt help. The baby was found in a shallow grave in a densely wooded area. His skull had been bashed in. IT had happened.