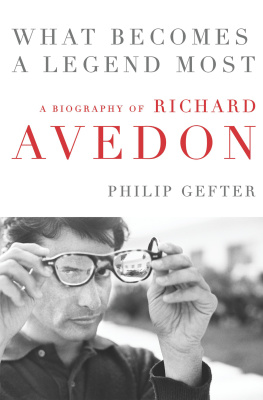

Philip Gefter - What Becomes a Legend Most: Richard Avedon

Here you can read online Philip Gefter - What Becomes a Legend Most: Richard Avedon full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2020, publisher: Harper, genre: Non-fiction. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

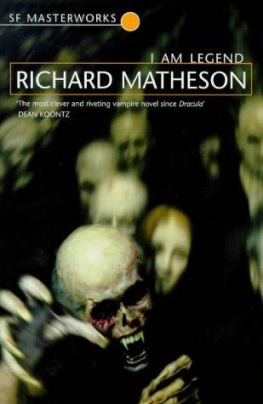

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:What Becomes a Legend Most: Richard Avedon

- Author:

- Publisher:Harper

- Genre:

- Year:2020

- Rating:3 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

What Becomes a Legend Most: Richard Avedon: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "What Becomes a Legend Most: Richard Avedon" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

What Becomes a Legend Most: Richard Avedon — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "What Becomes a Legend Most: Richard Avedon" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

For Richard Press

Fame is a bee.

It has a song

It has a sting

Ah, too, it has a wing.

EMILY DICKINSON

Contents

O n the occasion of her starring role as King Lear on Broadway, the great British actor Glenda Jackson, by then eighty-two years old, asserted that Shakespeare remains the most contemporary dramatist in the world because he really only ever asks three questions: Who are we? What are we? Why are we? These same existential questions underscore the body of portraiture produced by Richard Avedon in the second half of the twentieth century. We are all of the same species, he was saying, and with each portrait he made, regardless of whether it was of the Duke and Duchess of Windsor, Marilyn Monroe, Truman Capote, or a drifter in the American West, he rendered a specimen of our species to be contemplated in the context of his ongoing catalog of humanity, prompting us to consider ourselves over and over again, as if in mirror image: Who are we? What are we? Why are we? And, yet, in Avedons lifetime, he was dismissed as a celebrity photographeran intellectual slur that stuck to him as gum on his shoe, and to which he was often quick to reply: Dont think about who they are; just look at their faces.

Avedons 1957 portrait of Monroe is one of his most recognizable images. If all his portraits are self-portraitsMy portraits are much more about me than they are about the people I photograph, he said on more than one occasionthen the question of how to refer to this photograph presents an additional anomaly about the nature of portraiture: Do Andy Warhols silk screen multiples of Marilyn, for example, or Jackie, or Liz, constitute portraits of legendary icons, or are they Warhols first? A comparable example might be John Singer Sargents bravura portraits of society figures of the late nineteenth century that depict a class and an era with accomplished brushwork and daunting spontaneity. Yet we recognize the exquisite Sargent before identifying the woman in his risqu portrait, Madame X, say, as Virginie Gautreau. No anecdote better epitomizes this paradox than the one recounted about Picassos portrait of Gertrude Stein. When confronted by someone who claimed that the portrait didnt look anything like Stein, Picasso said with imposing confidence: It will. The same could be said of Avedons portrait in which Marilyn Monroe appears unmasked. It may not represent the public image of the radiant movie star, but it has fallen in place historically as Avedons Marilyn. That is true of all his portraits. They are recognizably Avedons first, even before the viewer identifies his subject.

Today, in the pantheon of portrait photographers, Avedon stands alongside Nadar (Gaspard-Flix Tournachon), who photographed in his Paris studio the significant artists, writers, musicians, and thinkers of nineteenth-century Second Empire France; Julia Margaret Cameron, who photographed the artists, poets, philosophers, and aristocrats of nineteenth-century Victorian England; August Sander, who made a chronicle of societal archetypes in early twentieth-century Germany; and, of course, his own contemporary, Irving Penn. All of them photographed the significant figures of their time, each one asserting a distinct visual signature that defines the artist as well as the period in which they each lived and worked. Avedons signature was the formality of a straight-on figure against the white nuclear backdrop, with a proscenium frame composed of the edges of the film printed as part of the imagethe ID picture taken to its apotheosis.

In his fashion work, he brought a native poetic impulse and youthful exuberance to his discovery of Paris after the Second World War and transformed the representation of womens fashion in photography into the defining look of an era. He knew that women are a foreign country, Judith Thurman writes about the young Avedon in her essay in Made in France. He also knew, like every other precocious young aesthete raised among philistines... that Paris is the capital of that foreign country.

In his lifetime, Avedon endured personal, as well as professional, prejudice. He was brought up in New York between the world wars, when anti-Semitism and homophobia forced him to make decisions that shaped the course of his life. His father, Jacob Israel Avedon, anglicized his name to Allan Jack Avedon, and his son grew up believing that, as a Jew, assimilation and aspiration were the same thing. Avedon had his nose surgically altered in 1941, at the age of seventeen, to appear less Jewish. Several years later, he began psychoanalysis to try to cure himself of unwanted homosexual feelings. He married (twice), a necessity in mid-twentieth-century America for anyone who wanted to have professional options and societal standing. By sheer force of will, and not a little talent, he rose to become the most successful fashion photographer in the world, and, then, among the greatest portrait photographersalong with Irving Penn, to whom he would become tethered in history as Picasso is to Matisse; Pollock to de Kooning; and Roth to Updike.

As an artist, Avedon found that the world of fashion did not satisfy the breadth of his curiosity and creativity. Avedon was like Fragonard, one colleague said about him. Like many decorative artists, he despised his gift. His gift became a noose around his neck (albeit one that was perpetually lucrative and made him very rich). He wanted to be taken seriously as an artist but was foiled by the bastard medium he embracedphotographywhich made the struggle to be seen as an artist that much more encumbered. In his final years, Avedon witnessed a respect for his chosen medium that had been long overdue in the art world and that he had had a hand in bringing about: his own tireless efforts to have his work shown in galleries and museums throughout his career tracked simultaneously with the rise in stature of the medium of photography itself.

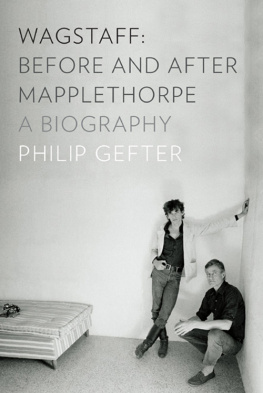

In Avedons lifetime, two other luminaries had instrumental roles in garnering respect for photography in the art world: the curator John Szarkowski had the institutional platform of the Museum of Modern Art on which to make his persistently eloquent case for photography as an art form of equal consequence among its fine art peers; and Sam Wagstaff, an institution of one and one of the very first photography collectors, who almost single-handedly established the art market for the medium. Avedon was third in this triumvirate, despite the fact that the curator and the collector refused to take his work seriously. Yet, in 1978, when Avedons fashion work was exhibited at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, it broke photography out of its circumscribed ghetto, unfurling his name on a huge banner in front of the most august museum in America and landing him on the cover of Newsweek, still then a pillar of journalism and an oracle of cultural significance. No other living photographer had situated himself so prominently in the public eye. For better or worse, Avedon became a household name. He is one of the major photographic artists of the twentieth century, and one of the most influential, said Mia Fineman, cocurator of his exhibition of portraits at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 2002. Practically every day youll come across an Avedon imitation. The portrait style he established has become part of the vocabulary of photography. That work is seminal, and his fashion work, too. He was groundbreaking in both.

I wrote this biography because of my belief in Avedon as one of the most consequential artists of the twentieth century, closer in his sweeping art-historical gesture toward flattening out the image on a two-dimensional surface to Andy Warhol than to Diane Arbus. While his fashion work was revolutionary in its timeessentially in the 1950s and 1960snot to mention stylish, debonair, and visually arresting, his portraiture was radical in its formal simplicity; monumental in its existential purity. Avedon advanced the genre, falling in place after August Sander. I set out to explore the combination of qualities and circumstances that formulated Avedons unique sensibility, which carried the allure of international glamour and, along with it, something profoundly sexy that was hard to define. In the riddle of that examination was my own quest to understand how the culture of the second half of the twentieth century evolved from a particular nexus in New York and Hollywood, in the years of my own youth, the 1950s and 1960s: Avedon was at the center of a profoundly influential group of individualsLeonard Bernstein, Truman Capote, James Baldwin, Allen Ginsberg, Harold Brodkey, Sidney Lumet, and Mike Nicholswho shaped the cultural life of the American century and whose music, books, and films clarified my own understanding of my time. Avedons world was a nourishing one to get lost in while I researched, contemplated, and laid out the story of his life. It was an exercise that confirmed a guiding belief of mine, one exemplified by Avedon himself: Know thy culture; know thyself.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «What Becomes a Legend Most: Richard Avedon»

Look at similar books to What Becomes a Legend Most: Richard Avedon. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book What Becomes a Legend Most: Richard Avedon and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.